SMITHSONIAN LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES

Mid-19th Century Reactions to a Laundry Invention

This mid-19th century advertising circular proposes a new idea for doing laundry. What it lacks in detailed description, it makes up for with powerful testimonials.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/75/26/75269141-fc05-43e5-b6de-77dcf623b3ef/h-twelvetree-twelvetrees-washing-pamphlet-header.jpg)

Today the task of laundry is simple. We load machines with clothes, add laundry detergent and softener, and check settings. But essentially, the modern washing machine and dryer do the job for us. However, in the mid-19th century, long before our modern appliances, it was not so easy. Laundry was time-consuming and labor-intensive, so perhaps this pamphlet describing a “really wonderful invention” sounded intriguing.

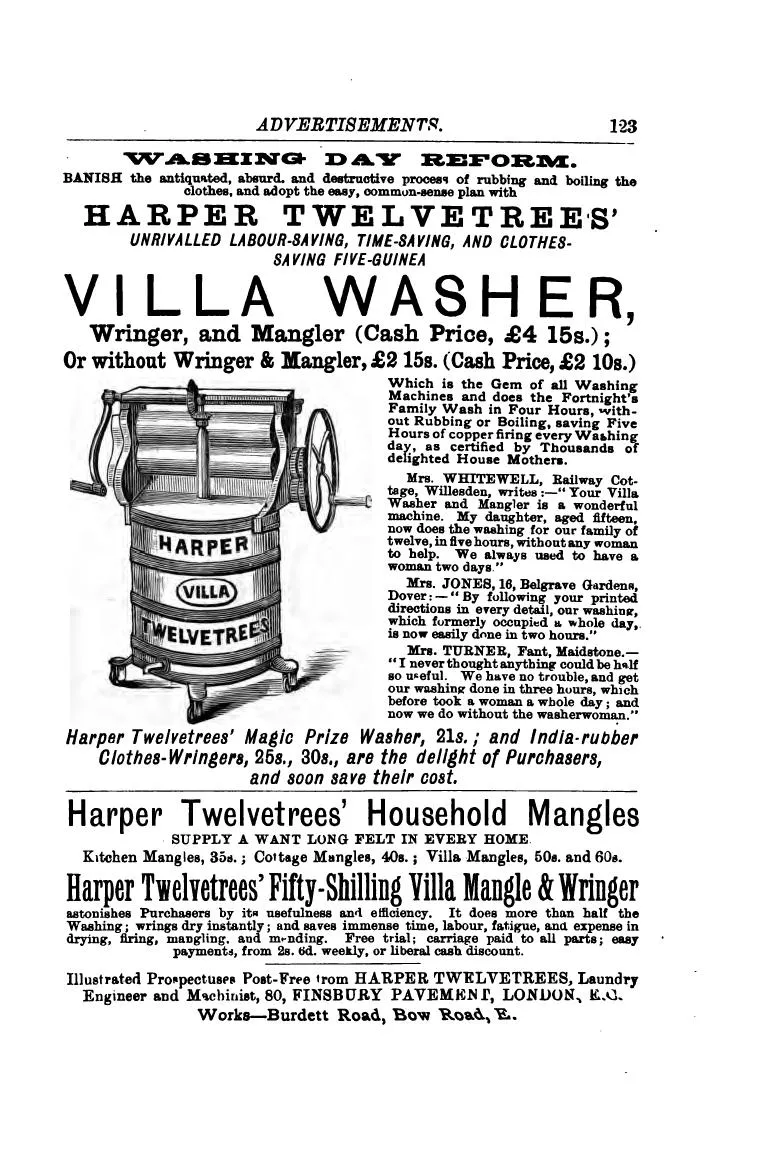

It proposed a method “to accomplish a large family wash before breakfast” without machines and without rubbing. The folded pamphlet is titled Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850) by H. Twelvetree, and as we can reason from one of the testimonials found within, H. Twelvetree was most likely Harper Twelvetree (or Twelvetrees).

It does not provide step-by-step instructions, details, or illustrations to describe this new method for washing clothes. Instead, it provides only general information about the plan along with testimonials and references of those who tried it. We might call this folded pamphlet an advertising circular, as it encourages mid-19th century readers to inquire for more information and to obtain the details from H. Twelvetree.

Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850) explains that this method was discovered by Professor Leibig who, for a sum of money, gave permission for the proprietor, H. Twelvetree, to use it. The washing plan combined “economy of time and money, with safety and simplicity.” Ordinary individuals, high officials, and institutions were already using it. There is also a mention that the washing plan had been tested by hundreds of editors of newspapers and periodicals, including some who are listed as references.

The pamphlet shares a few basic components of the plan. It required no rubbing, no machines, and no extra washing utensils. Previous knowledge was not necessary. It required water, but the substance used for washing was cheaper than soap. It did not include acid, turpentine, or camphene. It did not have an unwelcome odor. And, as the pamphlet claims, it would not injure those performing the wash or destroy the fabric being washed.

There are also two pages of testimonials which provide more information, particularly in regards to how people felt about using this new method. Similar emotions and feelings are found throughout the testimonials. Several mention their initial hesitation or skepticism but then share their surprise, delight, and satisfaction with the results. They mention advantages for their households, such as labor-saving and time-saving benefits in addition to the plan’s ability to efficiently and thoroughly wash clothes.

One of the testimonials is an excerpt from The Fairfax [Va.] News printed on November 24, 1849. It mentions an advertisement from the previous week in which they announced their trial of “a new plan of washing by Harper Twelvetree.” It continues by stating:

“The trial has now been made, and we are glad to say it is true. Our “gude wife,” who always opposed the idea of its being true, and who would not listen to a trial being made for a moment until we made the experiment, says, by following these directions, all the labor of rubbing is dispensed with, boiling the clothes thirty minutes only being substituted for it, and the article is washed in a much neater manner than it can be done in the usual way…”

The main purpose for this new idea might have been to wash clothes, but as some of the people found, there was a hidden benefit as well. On the first page, the pamphlet briefly suggests saving both soap and labor by re-using the same water for cleaning the house. Even though it does not go into great detail, we learn a bit more from a testimonial on the next page.

On March 13, 1850, Clementina Collier of Albany writes about an unexpected result of accidentally spilling water that had already been prepared with the ingredient to wash clothes. Due to this accident, Clementina Collier learned “that part of the floor on which the water was spilled looked much whiter than usual.” The testimonial continues:

“This induced me to try your plan for flooring, and I found it to succeed so well that I now have all my housecleaning done that way. It saves soap and the labor of scrubbing, and makes the wood of a better color. My plan is, after I have washed my clothes, to save the water, which then answers the purposes for flooring, wainscoting, &c…”

Twelvetree’s Washing Pamphlet (ca 1850) by H. Twelvetree is located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library. Interested in learning more about laundry in the 19th Century? A past blog post highlighting a Thomas Bradford & Co. trade catalog provides a glimpse into washing machines and related equipment in 1878.