SMITHSONIAN TROPICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Here’s the Scoop on Monkey Leadership

What makes a great leader? Grace Davis and Lucia Torrez lead a team working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute to understand leadership in capuchin and spider monkeys.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Grace_and_the_monkey_chase_Jpegs_9_of_58.jpg)

A seedy green glop of monkey poop plummets from the heavens, plopping onto Grace Davis’ platinum blond head. This is the second time today. What are the odds? Monkey project manager Lucia Torrez gently collects the lumps of poop in a twist-tied specimen bag, wiping Grace’s hair until only a fashionable pistachio-colored streak remains.

Grace and Lucia have been chasing monkeys for months. They get up before the sun, dress, fill their camelbacks with water and head to the dining hall for breakfast with the crew. Then it’s out to find the monkeys where they slept the previous evening.

For Grace and Lucia, monkeys lead the way to comprehending human sociality, just as they led them to Barro Colorado Island in Panama.

Grace has been a field biologist forever. As a kid, she filled muddy notebooks with sketches of the ducks in the ponds behind her house. “I even did my 8th grade science fair project on gorilla social behavior at the local zoo.” As an undergrad she traveled to study mountain gorillas in Rwanda and chacma baboons in South Africa, setting her up nicely to begin a PhD at the University of California, Davis.

The question she chose is about leadership. What makes a good (primate) leader?

According to new Smithsonian Secretary, Lonnie Bunch, “A good leader defines reality and gives hope.” A 1998 article by Daniel Goleman advocates emotional intelligence, “self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skill,” as the attributes of a great leader. Consultant Ian Davis told a group at the Stanford Graduate School for Business that excellent leaders are defined “not by what they are, not what they say, but what they actually do.” “Real leaders initiate stuff.”

Leaders persist through good and bad times. At the Smithsonian’s research station on Barro Colorado Island a fair bit is known about both: weather data goes back to the building of the Panama Canal in 1910. Primate field studies go back to Ray Carpenter’s pioneering work in the 1930’s.

In the past, tracking monkeys meant a lot of walking and a mega-dose of good luck. Then radio-tracking collared animals made it somewhat easier, but still involved following animals through the forest while carrying a hand-held antenna. In 2003 researchers installed a set of 7 fixed antennas on the island— Automated Radio Telemetry System (ARTS)—and Grace’s advisor, Meg Crofoot (now the director of the new Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior) was hired to work out the kinks in tracking up to 200 animals at a time—from agoutis to ocelots. By the end of her stint, she could sit comfortably in the lab and watch groups of collared capuchin monkeys, represented by neon-colored zig zags on a computer screen, as they moved around the forest.

By 2010, the ARTS system was disassembled, because the upgrade to a new satellite-based Global Positioning System (GPS) worked even under the leafy canopy of tropical rainforests. The latest version of GPS can pinpoint a cell phone, or an animal collar, within 30 centimeters.

Meg and colleagues went on to publish a cover article in Science in 2015, based on work at the Mpala Research Centre in Kenya where they GPS-tagged nearly an entire troop of baboons for the first time ever. Decision making in baboon troops turns out to be a highly democratic process. An individual saunters off in a certain direction. Others either ignore, or stand up and follow. When group members want to go in different directions, the majority rules—in short, baboons elect a leader by voting with their bodies.

Meg hired Nicaraguan biologist Lucia Torrez as her right-hand woman and field manager during her own post-doctoral project to understand group dynamics and conflict in capuchin monkeys. As Meg’s grad student, Grace continues to work with Lucia and a new team of students, interns and volunteers back on Barro Colorado Island. Which individuals lead groups of white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus) and spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi)?

“This is such a great system, because both monkey species are eating from the same trees, moving through the same areas and living on the same island, so we can really compare them,” Grace explained.

When engineers dammed the Chagres River to form the main channel of the Panama Canal in 1914, no spider monkeys remained on the mountaintop isolated as Barro Colorado Island. In the 1950’s, STRI director, Martin Moynihan released young spider monkeys he purchased at a market in Panama City.

Now roughly 45 of their descendants swing through the trees, dangling from prehensile tails. The largest of five monkey species on Barro Colorado, they eat mostly fruit. Spider monkeys split into smaller groups and then regroup as resources become scarce or abundant. They could be territorial in other situations, but there is only one group on the island, so there’s nothing limiting their movement.

“One project I’m working on with the spider monkeys is to test a simple idea called ‘Lead according to need’ or ‘social indifference’ because they put their own needs first,” Grace said. “It’s never been tested in the field with animals that have complex social systems. Monkeys driven to find a food source to fulfill their energetic requirements may be more motivated to be out in front. They’re the ones that are going to go find new resources first. It may be an adult female that’s lactating or a monkey that just didn’t get enough food the day before.”

On Valentine’s Day in the mid-dry season forest, leaves crunch under the soles of black rubber boots as the team starts up the slope, accompanied by a buzzing crescendo of cicadas. Grace turns on her radio to a blast of rock music.

“Did you hear that? That is sooo funny! 108FM!” The team is looking for radio signals from the monkeys’ radio collars and they are really lucky this year because they’ve got GPS collars on six capuchins and four GPS and four radio collars on spider monkeys.

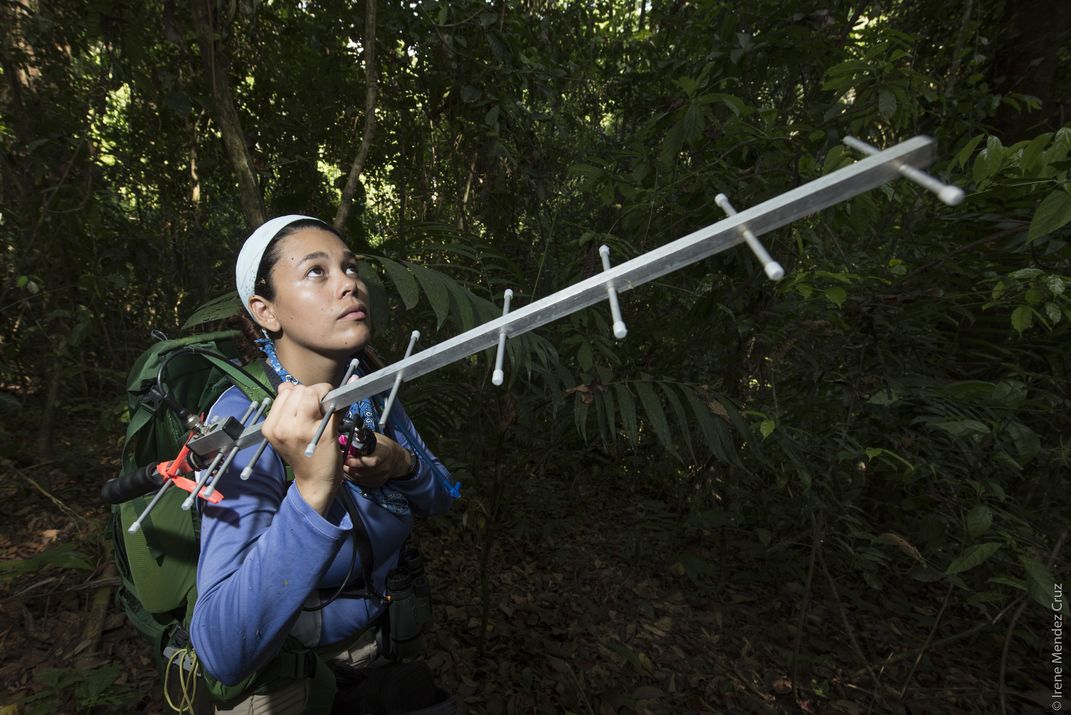

“There’s no way we could follow these monkeys if they didn’t have transmitters,” Grace says. “Just like radio stations, each monkey has a frequency. As I dial away from the number, if I can still hear the signal, the individual is close, and if I lose the signal, the monkey is farther away.”

Jean Concepcion, a student at Universidad de Chiriqui, one of Grace’s assistants on a fellowship from Panama’s science and technology office, SENACYT, turns on his radio. He types 314, into the receiver. That’s Bravo Luis, and he’s not too far away, probably about 600 meters up the slope.

Aulden Foltz, an undergraduate from Stanford, pulls up the ipad hanging on a strap around her neck and swipes to a photo-collage of Bravo, an older-looking capuchin. In some of the pictures his whiskers look bloody.

“He ate a baby squirrel,” she explains. “It was disgusting.”

As Grace pushes on up the trail and the signal gets louder, she says: “One of my favorite things about this island is Ray Carpenter’s story. He was the first field primatologist in the world and he worked here in the 1930’s and again in the fifties and sixties. We’re continuing to make primatology history where it first began.”

Carpenter, who studied howler monkeys, invented the standard techniques to observe primates in their natural habitats used by Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, Robert Sapolsky and other well-known primatologists.

This is the fourth year of Grace’s Ph.D. work. The last two field seasons were both El Niño years in Panama, hot and sunny, resulting in bountiful fruit crops, despite very dry conditions. She watched capuchins dipping their tails into tree holes where scarce water accumulates, sucking on them to retrieve the last drop.

Although the majority of their diet is fruit, capuchins eat almost anything they can get their hands on, and particularly love insects, eggs and even small rodents, birds, lizards and snakes. Capuchins live in fixed membership societies. They always hang with the same group as a defense against predators like harpy eagles and ocelots.

“I’ve seen a white hawk try to capture a baby capuchin off of its mother’s back,” Grace says.

Today the monkeys are likely to be in Dipteryx trees. Botanists call Dipteryx a keystone species because it fruits plentifully when other food in the forest is scarce. The papery brown outer coat of each fruit seals in sweet, date-like pulp around a woody seed.

Grace’s team radio tracks a monkey, following it into the next tree.

Everyone runs down the steep slope, trying not to slip on dry leaves, but also not to grab onto spiny palm saplings and watching out for matchstick-long black bullet ants that pack a sting far worse than any wasp. A friend who was stung by a Paraponera on the back of the neck said that it throbbed for nearly a day, despite a very hot shower and a bottle of rum. So far, everyone has been spared.

Now in place under a huge Dipteryx tree, each person on the team picks a monkey and starts talking into the voice recorder app on a mobile phone. They call this a focal sample:

“Moving. Eating. Moving.”

“Tasting. Eating. Discard.”

“A juvenile just exited going southeast.”

“Bravo, exit! Southeast.”

“I think yours exited, Maria.”

“Time?”

“Does anyone know what the number of this tree is?”

“Eleven.”

“Was Bravo last? I think Bravo was last.”

The Dipteryx trees on the island are almost out of fruit.

“This is my third dry season taking the same data on foraging decisions. Last month was the wettest January on record, and there’s way less food in the forest this year,” says Grace. “The monkeys are actually swallowing whole unripe fruits and the capuchins seem to be eating more insects. We’re watching to see what else they are eating and asking if they do more tasting, and take more chances eating unusual foods during this season when fruit is scarce.”

“They’ve also been travelling further, travelling faster—that makes our job exciting! And they’ve been taking shorter nap breaks in the afternoon. We’re collecting urine samples, so we’ll be able to tell if they’re more stressed, based on their hormones.”

Each student carries a big butterfly net covered with a plastic bag. When they see an animal peeing or pooping, they stick out the net and then pipette or collect anything that lands on the plastic bag in a screw-top test tube, label it and take it back to the lab. From the urine samples, they can determine the amount of c-peptide, a byproduct of insulin that indicates how much energy a monkey is taking in.

Despite the poor Dipteryx crop, there are other options for the monkeys, like the fruit of the Panama Tree, Sterculia apetala. In the same plant family as cacao plants, this canopy tree produces hard green capsules filled with oil-rich nuts. Mayas roasted the nuts and added them to their chocolate drinks, purportedly to give them an extra kick. The catch is that the inside of each capsule is lined with stinging hairs.

From the ground, we can see capuchins slamming the capsules against the branches of the tree to break them open, and I also think I see a capuchin wiping its chin again and again…perhaps because the irritating hairs are lodged in its fur.

“That’s Violeta! She’s the only one with eyebrows.”

The whole team is scrambling down slope to the next tree.

This time the base station in Cassidy Martin’s backpack starts beeping. “That means that it’s downloading all of the movement data from a monkey. We often get three or four days of GPS data, and we can compare that to the data we are taking in our field notebooks,” says Cassidy, an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

After doing the focal sample, Grace appoints Aulden to pick up fruit. In the evening, they will sort the fruit by tree, cut off the pulp, weigh it and then send it to a lab for nutrient analysis so they can see how the food quality of the trees compare as the season progresses and as the fruit ripens.

“The reason there are so many people in this group is that once the monkeys enter a feeding tree, I can follow an adult male, Lucia can follow an adult female, someone can follow a juvenile at the same time and see how those behaviors all end up predicting what the group is doing.”

Lucia’s voice crackles over the walkie-talkie.

“I’m watching Fresa.”

Lucia calls out more spider monkey names like fruit salad: “…Naranja, Piña, Limon.”

Grace and Lucia communicate, not only by walkie-talkie, but telepathically.

These two women are clearly the leaders of this group of monkey watchers. Their stamina, hunger for knowledge and curiosity kept a group of up to seven people on the run, all day long for nearly six months.

“So far, adult females seem to be the leaders of the capuchin groups,” Grace says.

Soon they will have the data to be sure.

P.S. For the original version of this story with several video clips, please see the news section of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute website.