SMITHSONIAN TROPICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE

A Turtle Time Capsule: DNA Found in Ancient Shell

Paleontologists discover possible DNA remains in fossil turtle that lived 6 million years ago in Panama, where continents collide

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/21/6a/216a0951-62b7-4e49-9151-fc246fb1c9d3/2_1_fossil_genes.jpg)

Currently, only seven species of sea turtles exist. Among them are two in the genus Lepidochelys: the olive ridley and the Kemp’s ridley. Despite being among the most common sea turtles in much of the Caribbean Sea and elsewhere, little is known about their history or evolution. The remains of a turtle shell recently found on Panama’s Caribbean coast represent the oldest fossil evidence of these turtles ever found.

The discovery of the fossil in the Chagres Formation indicates that this turtle lived approximately 6 million years ago in Panama in the upper Miocene Epoch, a time when the world was getting cooler and drier, with ice accumulating at the poles, sea levels falling and reduced rainfall.

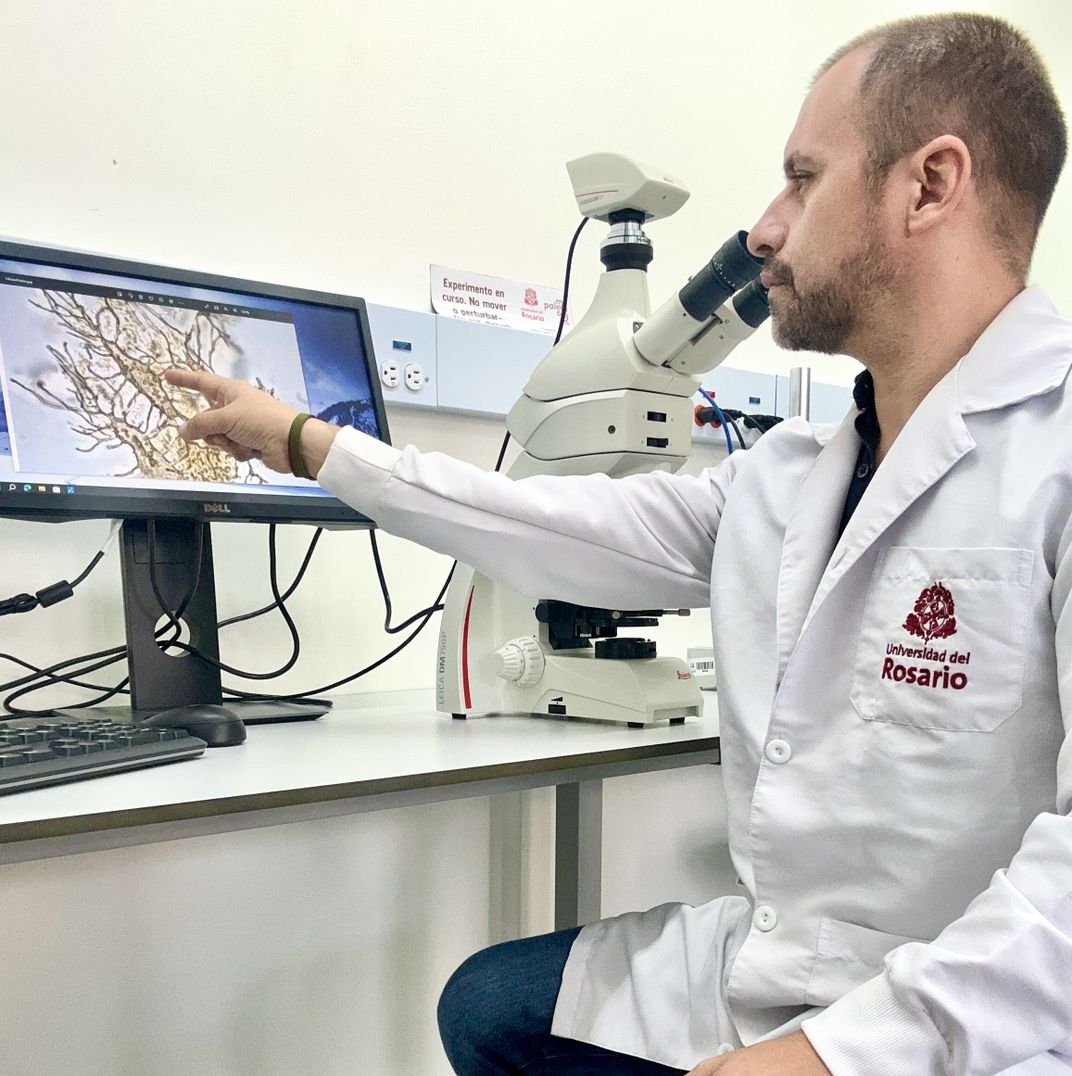

The remains were analyzed by a team of paleontologists led by Dr. Edwin Cadena of the Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá, Colombia, who is also a research associate at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama.

In addition to finding the oldest record of Lepidochelys turtles, the researchers discovered something unexpected in the fossil bones of this turtle: traces of DNA. After detecting preserved bone cells (osteocytes) with nucleus-like structures, they used a solution called DAPI to test for the presence of the genetic material.

“Within the entire vertebrate fossil record on the planet, this had only been previously reported in two dinosaur fossils, including one of Tyrannosaurus rex,” Dr. Cadena pointed out, referring to the ancient DNA.

This discovery gives the fossil vertebrates preserved on the Caribbean coast of Panama enormous importance not only for understanding biodiversity at the time of the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama, which divided the Caribbean from the Pacific and joined North and South America, but also for understanding the preservation of soft tissues and possible original living matter such as proteins and DNA, essential components of an emerging field known as Molecular Paleontology.

“The Caribbean fossils from Panama that we have managed to rescue over the years are helping to rewrite the history of marine vertebrates of the Isthmus,” said Carlos De Gracia, co-author of the study and a doctoral fellow affiliated with STRI who is funded by Panama’s Office for Science and Technology (SENACYT).

This research resulted from cooperation between the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the Universidad del Rosario. It was published today in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

STRI, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The institute furthers the understanding of tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.