SMITHSONIAN TROPICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE

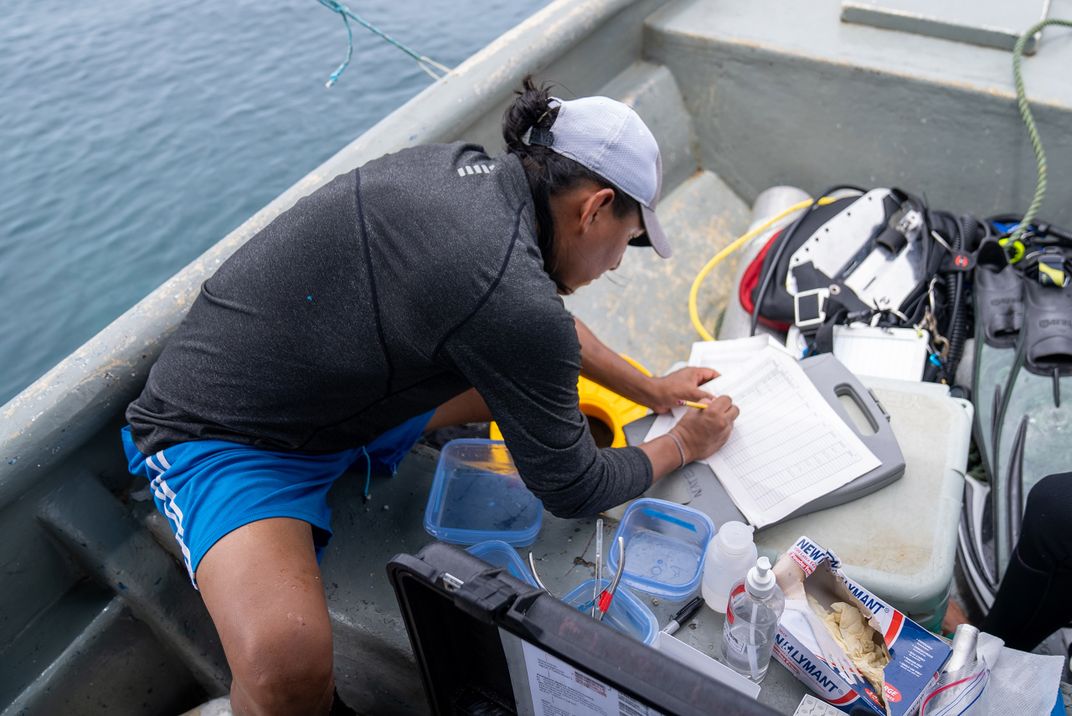

Indigenous Marine Scientist Studies Fish Feeding Evolution in Panama

Through advanced isotopic analyses, Rodnyel Arosemena seeks to understand how fish in the Caribbean and the Pacific that had a common ancestor take advantage of the resources of their different environments today.

:focal(1280x859:1281x860)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/d1/17d10c0e-9695-45d3-b086-caa210f0dfa6/2_a7s08978_rodnyel_arosemena_1.jpg)

Rodnyel Arosemena is of Dule (from Guna Yala) descent but grew up in the city. Unlike his parents, who grew up in the Guna Yala region, the Panamanian Caribbean Sea was not central to his childhood. His first memory of the beach is at the age of eight, but once he started college, his roots claimed him back: he is now a marine biologist. He is also one of the few people in the world trained in compound-specific stable isotope analysis of amino acids (CSIA-AA).

Arosemena was chosen to train in CSIA-AA after a year working with various marine labs at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI). This led him to spend two months at the University of Hong Kong, where STRI postdoctoral researcher Jon Cybulski taught him how to analyze fish muscle samples with the cutting-edge technique for a project on sister fish species across the isthmus of Panama.

The project led by STRI scientist Matthieu Leray aims to understand how the diet and resource utilization of fish sharing a common ancestor differs. These species, once connected but now geographically separated due to the formation of the isthmus, have adapted to distinct environmental conditions in the Caribbean and the Pacific.

“Their dietary evolution can be evaluated by observing the animals’ eating habits, but the stable isotopes’ technique provides a more specific and detailed analyses,” Arosemena explains.

Most elements, such as carbon and nitrogen, possess multiple stable isotopes with slight differences in atomic masses. These variations cause them to behave differently biologically from one another, leading to varying ratios within an animal's body. In other words, analyzing their ratios may unveil what an animal has been eating during most of its life, shedding light on its food sources and environmental influences.

“Samples of fish muscles are used to examine the transfer of each amino acid during the feeding process, as well as how each organism takes advantage of nutrients and energy, providing a greater level of detail on resource use,” says Arosemena.

It is expected that, due to the elevated nutrient levels in the Pacific, there will likely be a wider range of dietary choices for the fish there compared to the Caribbean region.

“The sister species separated by the isthmus of Panama are a unique system to understand how feeding strategies evolve in marine organisms in response to different environmental conditions,” said Leray. “This research is not only very important for understanding the mechanisms of adaptation and speciation in marine organisms, but it will also provide insights into how marine fishes may be able to cope with climate change related impacts, such as changes in prey availability or shifts in habitat suitability.”

For Arosemena, this and other experiences at the Smithsonian have allowed him to enrich the knowledge he had already acquired in college and have motivated him to continue advancing in his scientific career in marine biology.

“I am considering applying for a master's degree and continuing to dedicate myself to research,” Arosemena said. “All my work so far at STRI has been related to concepts such as evolution, resilience and adaptation and I believe that fish, because of their great diversity, would be an excellent starting point for my career.”

Headquartered in Panama, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. The institute furthers the understanding of tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.