Music at the White House: From the 18th to the 21st Centuries

A guest post by Elise Kirk, author of Music at the White House

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/963_HarpersBazaar_X_color.jpg)

A guest post by Elise Kirk, author of Music at the White House

Author Elise Kirk recently released a revised edition of her authoritative history, Music at the White House: From the 18th to the 21st Centuries. In honor of President's Day, we offer an excerpt from the chapter on George Washington, below. Ms. Kirk will be speaking at the Smithsonian on Thursday, May 17, 2018 at 6:45 p.m. as part of a four-part series co-sponsored by the Smithsonian Associates and the White House Historical Association, "The Most Famous Address in Washington: Perspectives on White House History." Visit the Smithsonian Associates website for more information and to purchase tickets. Participants receive a copy of Music at the White House.

Excerpt from Music at the White House: From the 18th to the 21st Centuries, written by Elise Kirk

Chapter One: Musical Life at Home

George Washington

Washington, who enjoyed concerts almost as much as theatrical events, attended several of Reinagle's "City Concerts" while in Philadelphia for the 1787 Constitutional Convention. On May 29, for example, he heard works by Franz Joseph Haydn and Giuseppe Sarti as well as by the local composers William Brown, Henry Capron, and Reinagle himself. Two weeks later "a new overture" by Reinagle was featured along with Capron's Violoncello Concerto and overtures by Niccoló Piccinni and Bach, probably C. P. E. Bach, whom Reinagle knew and admired. Presented on June 12, this concert was also attended by Washington. He noted in his journal: "Dined and drank tea at Mr. Morris's. Went afterwards to a concert at the City Tavern."

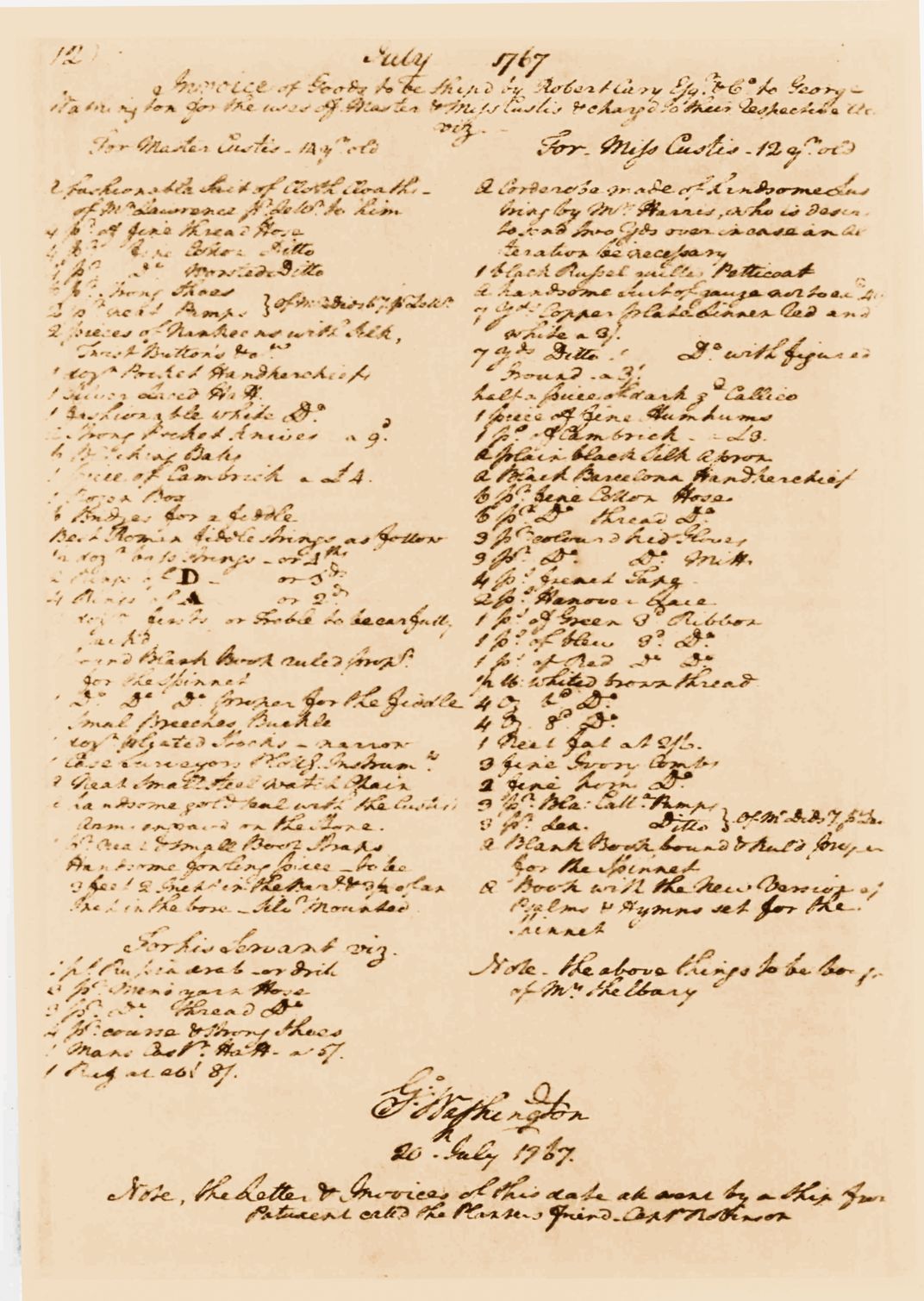

The associations that Washington made through the City Concerts subscription series resulted in his hiring three of the musicians to teach his adopted granddaughter, Nelly Custis: Reinagle from 1789 to 1792, and John Christopher Moller and Capron for the remainder of Washington's presidency. Moller came to America from London, settling in Philadelphia and later in New York. A codirector of the City Concerts with Reinagle, he was also one of the city's first music publishers and dealers. Shortly after he moved to New York in 1795, he published an edition of Philip Phile's "The President's March" with a march of his own on the same page. Phile's tune, played often for Washington in various editions, was set to verse by Joseph Hopkinson in 1798, thus achieving immortality as the popular national song "Hail Columbia. "

Reinagle, in his turn, also found opportunity to eulogize the president in music. He chose Washington's famous journey from Mount Vernon to New York City to take the Oath of Office in Federal Hall, April 30, 1789. Reinagle's "Chorus sung before General Washington as he passed under the Triumphal Arch raised on the Bridge at Trenton, April 21, 1789" was "Set to Music and Dedicated by Permission to Mrs. Washington," as the title page indicates. On the other side of this page is a charming description of a group of young girls robed in white, singing as they strewed flowers before the impressed general:

Welcome mighty chief! once more

Welcome to this grateful shore

Now no mercenary Foe

Aims again the fatal blow.Virgins fair and Matrons grave,

Those thy conquering Arms did save,

Build for thee Triumphal Bowers

Strew, ye fair, his way with flowers,

Strew your Hero's way with Flowers.

Reinagle's piece was probably not the version sung by these young women, however. Aside from the fact that it is set in three parts with the lowest part written in the bass clef, a concert presented on September 22, 1789, featured a piece advertised as "a chorus to the words which were sung as General Washington passed the bridge at Trenton-the music now composed by Mr. Reinagle." The key word here is "now." John Tasker Howard believes the words were originally sung to the music of George Frideric Handel's "See the Conquering Hero Comes" from Judas Maccabaeus and that Reinagle's was a later setting, not the music used at Trenton. While this does not agree with the scholar Vera Lawrence's conclusions, it does not necessarily refute her assertion that Reinagle's piece is the first music to have been composed for a president of the United States.

More than any other president, Washington has been sentimentalized, emulated, monumentalized, and deified. Even before he began his eight years in office as the first president, Americans thought of him as a demigod. A nation with scant history of its own, America seemed to turn to the epic heroism of classical civilizations to satisfy its political and cultural psyche. Indeed, the statesman Francis Hopkinson even composed an allegorical oratorio, The Temple of Minerva, that depicted the goddess Minerva joining with the Genius of America and the Genius of France in praise of General Washington and the French-American Alliance. How the good general and his lady must have relished this musical tribute when they heard it first performed at a fashionable private gathering in Philadelphia on December 11, 1781! And when the state of Washington was erected in New York City's Bowling Green Square in 1792 where the image of George III once stood, American loyalties were transferred once and for all to a new hagiolith-a new "figure upon the stage." According to the historian Daniel Boorstin, "A deification which in European history might have required centuries was accomplished here in decades."

Among the panegyrics that have surrounded the image of Washington over the years are the tales of his musical prowess, his abilities to play the flute and violin. He played neither, although he may have picked up the fipple flute on occasion and blown a note or two to entertain his step-grandchildren. When Francis Hopkinson, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and an accomplished musician, dedicated to Washington his "Seven Songs for the Harpsichord" (published by J. Dobson in Philadelphia in 1788), the general admitted, "I can neither sing one of the songs, nor raise a single note on any instrument to convince the unbelieving." Washington, however, made sure his stepchildren played musical instruments: John the violin and Martha ("Patsy") the spinet.

A lyrical history of the American presidency and people, this is the story of a show that goes on. Elise Kirk traces the story of more than 200 years of musical performance in the White House to present the tale of the American process of music-making-how music in a democracy has been absorbed, shaped, transformed, and perceived from the period of George Washington to early in the Donald J. Trump administration. Whether dramatic or abstract, vernacular or cultivated, music can mold the political process and shape a historic event in a manner like no other. The new edition of Music at the White House was the winner of the 2017 USA Book News Awards, Performing Arts Category. The book is available for purchase from the White House Historical Association.