Reflections on the Puerto Rican Plena, Post-Hurricane Maria

Some musical genres are just particular—particular to a region or a community, without aspiring to be universally relevant or to commercially conquer new audiences. I think of the plena this way, an island-born genre that is performed throughout the Puerto Rican diaspora to nourish a collective sense of identity, memory, and feeling. It is a rhythmic, tambourine (pandero/pandereta) and voice-based genre that was created to share local stories (often described as a spoken newspaper). Its beat, mobile instrumentation, and participatory singing make it perfect for processions, as well as impromptu concerts and protests. The plena is a genre with songwriters who really have something to say about the historical and contemporary experiences of Puerto Ricans on and off the island. It is similar to other regional genres, like the gaita zuliana from Venezuela or Trinidad’s calypso, which are deeply steeped in the political and social contexts of their listeners.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Pandereta_NMAH-AHB2006q05029.jpg)

Some musical genres are just particular—particular to a region or a community, without aspiring to be universally relevant or to commercially conquer new audiences. I think of the plena this way, an island-born genre that is performed throughout the Puerto Rican diaspora to nourish a collective sense of identity, memory, and feeling. It is a rhythmic, tambourine (pandero/pandereta) and voice-based genre that was created to share local stories (often described as a spoken newspaper). Its beat, mobile instrumentation, and participatory singing make it perfect for processions, as well as impromptu concerts and protests. The plena is a genre with songwriters who really have something to say about the historical and contemporary experiences of Puerto Ricans on and off the island. It is similar to other regional genres, like the gaita zuliana from Venezuela or Trinidad’s calypso, which are deeply steeped in the political and social contexts of their listeners.

This summer I had the privilege of working with Los Pleneros de la 21 at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. This meant organizing an epic concert, moderating an onstage conversation about music and Puerto Rican identity, and interviewing the founder of the group, Juan "Juango" Gutiérrez in a video-recorded oral history. A conservatory-trained percussionist and a National Heritage Fellow, Gutiérrez makes and produces music, concerts, and workshops with the purpose of strengthening the resilience of the Puerto Rican people, and honoring the knowledge and musical traditions of his island’s ancestors.

This isn’t to say that non-Puerto Rican audiences can’t relate to plena. In a city like New York, where non-profit group Los Pleneros de la 21 are based, about 25% of the population is of Caribbean descent, with an overlapping Latino population from diverse parts of Latin America. In terms of rhythms and instruments, the plena is both familiar and distinct to some of New York’s largest ethnic communities, like Jamaicans, Colombians, Dominicans, Haitians, and others. The hand-held panderos, uncommon in most Latin American music outside of Brazilian samba and other carnival music traditions, provide the genre’s signature sound which is energizing and welcoming; plena has its own distinct signature but it is musically legible to audiences worldwide. Many non-Puerto Ricans dig the music, community, and tradition around the plena and have learned to play the genre.

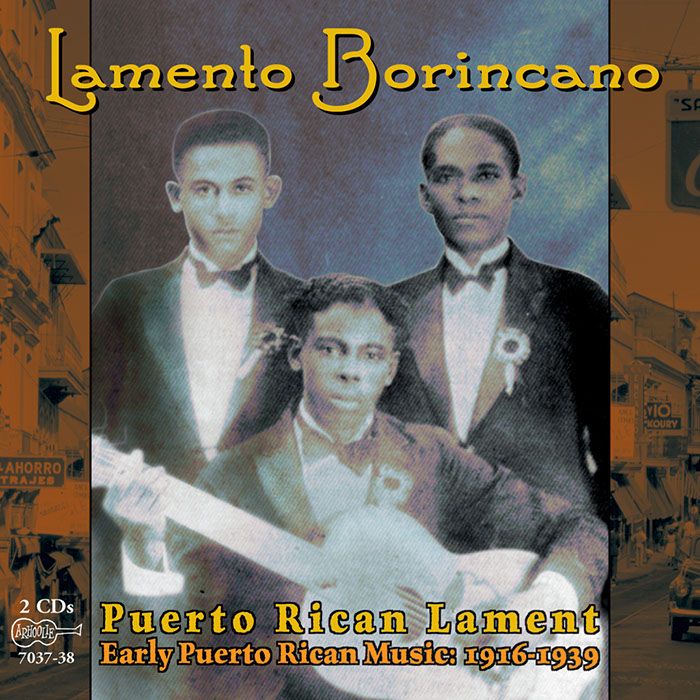

The history of plena from its inception reflects the exchanges between Puerto Rican and other Afro-Caribbean musical traditions. West Indian migrants to Puerto Rico probably introduced the plena’s basic musical form to the island in the late 1800s. In the following century, as Caribbean bands cross-pollinated each other’s musical circuits and listened to each other’s recordings, the plena was periodically interpreted by bands from Haiti, Martinique, Venezuela, and other neighboring places, especially in the 1950s and 60s. Many commercially-oriented Puerto Rican bands that included plena in their repertoire, starting with one of the pioneers of the recorded genre, Manuel “Canario” Jiménez, and continuing through the second half of the 1900s with the orchestras of Cesar Concepción, Cortijo, Mon Rivera, and Willie Colón, among others, were interested in inserting the plena into a contemporary repertoire of Caribbean and Afro-diasporic music styles.

Despite the respect for tradition and for the artists and elders who maintained the music, plena has never been stagnant. Its artists and audiences are not frozen in a repertoire of music, instrumentation, or dance moves. For example, some of the early recordings of Canario’s group feature the accompaniment of the rarely-used accordion, and the ballroom-adapted plenas of the 1950s were inevitably fused with mambo rhythms of the day. More contemporary groups like Atabal, Los Pleneros de la 21, and Viento y Agua have changed their instrumentation over time, with the latter group in particular breaking new ground in its musical arrangements and cross-genre conversations. Many in the new generation of pleneros (musicians who play the plena) are formally trained—the plena is something that they come to study in university or in formal workshops. The street corner jam session which was the cradle of the plena is mostly a bygone memory, but the soul of the music, with its messages of cultural resistance, humor, and endurance against the odds remains the same. The plena is more timely than ever, renewing the energy of Puerto Ricans and offering a popular musical space to comment and reflect on the future of the island and its people.