The Venus Flytrap’s Lethal Allure

Native only to the Carolinas, the carnivorous plant that draws unwitting insects to its spiky maw now faces dangers of its own

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Venus-Flytrap-captured-katydid-631.jpg)

As I slogged through black swamp water, the mud made obscene smooching noises each time I wrenched a foot free. “Be careful where you put your hands,” said James Luken, walking just ahead of me. “This is South Carolina”—home to multitudinous vipers, canoe-length alligators and spiders with legs as thick as pipe cleaners. Now and then Luken slowed his pace to share an unnerving navigational tip. “Floating sphagnum moss means the bottom is solid—usually.” “Copperheads like the base of trees.” “Now that is true water moccasin habitat.”

Our destination, not far from the headwaters of the Socastee Swamp, was a cellphone tower on higher ground. Luken had spotted a healthy patch of Venus flytraps there on an earlier expedition. To reach them, we were following a power-line corridor that cut through oval-shaped bogs called Carolina bays. Occasionally Luken squinted at a mossy spot of earth and declared that it looked “flytrappy.” We saw other carnivorous species—lippy green pitcher plants and pinkish sundews no bigger than spitballs—but there was no sign of Dionaea muscipula.

“This is why they call them rare plants,” Luken called over his shoulder. “You can walk and walk and walk and walk and not see a thing.”

Luken, a botanist at Coastal Carolina University, is one of the few scientists to study flytraps in the wild, and I was starting to understand why he had so little competition.

A shadow of a vulture glided over us and the sun glowered down. To pass the time Luken told me about a group of elementary-school teachers he’d recently led into a salt marsh: one had sunk nearly up to her neck in mud. “I really thought we might lose her,” he said, chuckling.

As we neared the cellphone tower, even Luken began to look a little discouraged. Here the loblolly and longleaf pines were shriveled and singed-looking; wildfires that had roared through the Myrtle Beach region apparently reached the area. I sipped at the last of my water as he scouted for surviving flytraps in the margins of a newly dug fire line.

“Give me your hand,” he said suddenly. I did, and he shook it hard. “Congratulations. You’re about to see your first flytrap.”

Venus flytraps’ considerable eccentricities have confined them to a 100-mile-long sliver of habitat: the wet pine savannas of northern South Carolina and southern North Carolina. They grow only on the edges of Carolina bays and in a few other coastal wetland ecosystems where sandy, nutrient-poor soil abruptly changes from wet to dry and there’s plenty of sunlight. Fewer than 150,000 plants live in the wild in roughly 100 known sites, according to the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

Instead of absorbing nitrogen and other nutrients through their roots, as most plants do, the 630 or so species of carnivorous plants consume insects and, in the case of certain Southeast Asian pitcher plants of toilet-bowl-like proportions, bigger animals such as frogs, lizards and “the very, very occasional rodent,” says Barry Rice, a carnivorous plant researcher affiliated with the University of California at Davis. The carnivores are particularly abundant in Malaysia and Australia, but they’ve also colonized every state in this country: the Pine Barrens of coastal New Jersey are a hot spot, along with several pockets in the Southeast. Most varieties catch their prey with primitive devices like pitfalls and sticky surfaces. Only two—the Venus flytrap and the European waterwheel, Aldrovanda vesiculosa—have snap traps with hinged leaves that snag insects. They evolved from simpler carnivorous plants about 65 million years ago; the snap mechanism enables them to catch larger prey relative to their body size. The fossil record suggests their ancestors were much more widespread, especially in Europe.

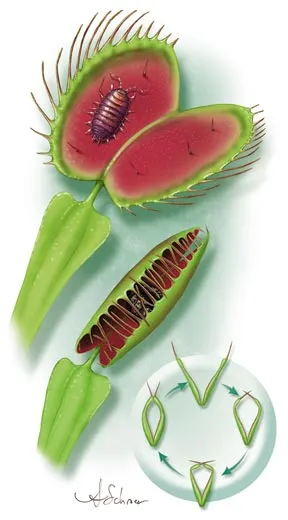

Flytraps are improbably elaborate. Each yawning maw is a single curved leaf; the hinge in the middle is a thick vein, a modification of the vein that runs up the center of a standard leaf. Several tiny trigger hairs stand on the leaf’s surface. Lured by the plants’ sweet-smelling nectar glands, insects touch the trigger hairs and trip the trap. (A hair must be touched at least twice in rapid succession; thus the plant distinguishes between the brush of a scrambling beetle and the plop of a raindrop.) The force that closes the trap comes from an abrupt release of pressure in certain leaf cells, prompted by the hair trigger; that causes the leaf, which had curved outward, to flip inward, like an inside-out soft contact lens snapping back into its rightful shape. The whole process takes about a tenth of a second, faster than the blink of an eye. After capturing its prey, a flytrap excretes digestive enzymes not unlike our own and absorbs the liquefying meal. The leaf may reopen for a second or even a third helping before withering and falling off.

The plant, a perennial, may live 20 years or maybe even longer, Luken speculates, though nobody knows for sure. New plants can grow directly from an underground shoot called a rhizome or from seeds, which typically fall just inches away from the parent: flytraps are found in clumps of dozens. Ironically, the traps rely on insects for pollination. In late May or early June, they sprout delicate white flowers, like flags of truce waved at bees, flies and wasps.

The first written record of the Venus flytrap is a 1763 letter from Arthur Dobbs, governor of North Carolina, who declared it “the great wonder of the vegetable world.” He compared the plant to “an iron spring fox trap” but somehow failed to grasp the ultimate fate of the creatures caught between the leaves—carnivorous plants were still an alien concept. The flytraps were more common then: in 1793, the naturalist William Bartram wrote that such “sportive vegetables” lined the edges of some streams. (He applauded the flytraps and had little pity for their victims, the “incautious deluded insects.”)

Live plants were first exported to England in 1768, where people referred to them as “tipitiwitchets.” A British naturalist, John Ellis, gave the plant its scientific name: Dionaea is a reference to Dione, mother of love goddess Venus (some believe this was a bawdy anatomical pun about the plant’s half-closed leaves and red insides), and muscipula means “mousetrap.”

Ellis also guessed the plant’s dark secret. He sent a letter detailing his suspicions, along with some dried flytrap specimens and a copperplate engraving of a flytrap seizing an earwig, to the great Swedish botanist and father of modern taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus, who apparently didn’t believe him. A carnivorous plant, Linnaeus declared, was “against the order of nature as willed by God.”

A hundred years later, Charles Darwin was quite taken with the notion of flesh-eating foliage. He experimented with sundews he found growing on the heaths of Sussex, feeding them egg whites and cheese, and was particularly charmed by the flytraps that friends shipped from the Carolinas. He called them “one of the most wonderful [plants] in the world.” His little-known treatise, Insectivorous Plants, detailed their adventuresome diet.

Darwin argued that one feature of the snap trap’s structure—the gaps between the toothy hairs that fringe the trap’s edges—evolved to allow “small and useless fry” to wiggle free so the plants could focus their energies on meatier bugs. But Luken and his colleague, aquatic ecologist John Hutchens, recently spent a year inspecting exoskeletons pried from snapped traps before ultimately siding against Darwin: flytraps, they found, ingest insects of all sizes. They also noticed that flytraps don’t often trap flies. Ants, millipedes, beetles and other crawling creatures are much more likely to wander into jaws opened wide on the forest floor.

Because flytrap leaves are used to grab dinner, they harvest sunlight inefficiently, which stunts their growth. “When you modify a leaf into a trap, let’s face it, you’ve limited your ability to be a normal plant,” Luken says. Perhaps the most famous Venus flytrap, Audrey Junior, the star of the 1960 movie Little Shop of Horrors, is garrulous and towering, but real flytraps are meek things only a few inches tall. Most of the traps are barely bigger than fingernails, I realized when Luken at last pointed out the patch we’d been looking for. The plants were a pale, tender, almost tasty-looking green, like a garnish for a trendy salad. There was something slightly pitiful about them: their gaping mouths reminded me of baby birds.

Luken is a transplant. At his previous post at Northern Kentucky University, he concentrated on Amur honeysuckle, an invasive shrub from China that is spreading in the eastern United States. But he wearied of the eradication mentality that accompanies exotic species management. “People want you to be spraying herbicides, cutting, bringing bulldozers in, just getting rid of it,” he says. The wild Venus flytrap, by contrast, is the ultimate native species, and though seldom studied, it is widely cherished. “It’s the one plant that everybody knows about,” he says. Moving to South Carolina in 2001, he marveled at the frail, green wild specimens.

Always rare, the flytrap is now in danger of becoming the mythical creature it sounds as if it should be. In and around North Carolina’s Green Swamp, poachers uproot them from protected areas as well as private lands, where they can be harvested only with an owner’s permission. The plants have such shallow roots that some poachers dig them up with butcher knives or spoons, often while wearing camouflage and kneepads (the plants grow in such convenient clumps that flytrappers, as they’re called, barely have to move). Each pilfered plant sells for about 25 cents. The thieves usually live nearby, though occasionally there’s an international connection: customs agents at Baltimore-Washington International Airport once intercepted a suitcase containing 9,000 poached flytraps bound for the Netherlands, where they presumably would have been propagated or sold. The smuggler, a Dutchman, carried paperwork claiming the plants were Christmas ferns.

“Usually all we find are holes in the ground,” says Laura Gadd, a North Carolina state botanist. Poachers, she adds, “have almost wiped out some populations.” They often strip off the traps, taking just the root bulb. More than a hundred can fit in the palm of a hand, and poachers fill their pockets or even small coolers. Gadd believes that the poachers are also stealing the flytraps’ tiny seeds, which are even easier to transport over distances. Many of the poached plants may surface at commercial nurseries that purchase flytraps without investigating their origins. It’s almost impossible to catch perpetrators in the act and the penalty for flytrap poaching is typically only a few hundred dollars in fines. Gadd and other botanists recently experimented with spraying wild plants with dye detectable only under ultraviolet light, which allows state nursery inspectors to identify stolen specimens.

There have been some victories: last winter, the Nature Conservancy replanted hundreds of confiscated flytraps in North Carolina’s Green Swamp Preserve, and the state typically nabs about a dozen flytrappers per year. (“It’s one of the most satisfying cases you can make,” says Matthew Long of the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, who keeps a sharp eye out for hikers with dirty hands.) Gadd and others are pushing for stronger statewide protections that would require collection and propagation permits. Though North Carolina has designated the flytrap as a “species of special concern,” the plant doesn’t enjoy the federal protections given to species classified as threatened or endangered.

In South Carolina, the main danger to flytraps is development. The burgeoning Myrtle Beach resort community and its suburbs are rapidly engulfing the flytrap zone. “When you say Myrtle Beach you think roller coaster, Ferris wheel, high-rise hotel,” Luken says. “You don’t think ecological hot spot. It’s a race between the developers and the conservationists.”

Many flytraps are located in a region formerly known as the impassable bay, a name I came to appreciate during my hike with Luken. A densely vegetated area, it was once considered so worthless the Air Force used it for bombing practice during World War II. But much of what was once impassable is now home to Piggly Wiggly supermarkets, bursting-at-the-seams elementary schools and mega-churches with their own softball leagues. Wherever housing developments sprout, backhoes gobble at the sandy dirt. For now the wilderness is still a vivid presence: subdivision residents encounter bobcats and black bears in their backyards, and hounds from nearby hunting clubs bay past cul-de-sacs in pursuit of their quarry. But flytraps and other finicky local species are being edged out. “They’ve basically been restricted to protected areas,” Luken says.

Recently, Luken and other scientists used a GPS device to check on wild flytrap populations that researchers had documented in the 1970s. “Instead of flytraps we’d find golf courses and parking lots,” Luken says. “It was the most depressing thing I ever did in my life.” Roughly 70 percent of the historic flytrap habitat is gone, they found.

Perhaps the greatest threat is wildfire, or rather the lack thereof. Flytraps, which need constant access to bright sunlight because of their inefficient leaves, rely on fires to burn away the impenetrable underbrush every few years. (Their rhizomes survive and later the flytraps grow back.) But the Myrtle Beach area is now too densely populated for small fires to be allowed to spread naturally, and people complain about the smoke from prescribed burns. So the underbrush thickens until the flytraps are smothered. Moreover, with tinder collecting for years, there’s an increased danger of a fierce, uncontrollable blaze like the one that ravaged the region in the spring of 2009, destroying some 70 homes. Such conflagrations are so hot they can ignite the ground. “Nothing,” Luken says, “can survive that.”

Aficionados have cultivated flytraps almost since their discovery. Thomas Jefferson collected them (during his stay in Paris in 1786, he requested a shipment of the seeds of “the Sensitive Plant,” perhaps to wow Parisians). A few decades later, Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife, the green-thumbed Empress Josephine, grew flytraps in the gardens of the Château de Malmaison, her manor house. Over the years breeders have developed all sorts of designer varieties with jumbo traps, extra-red lips and names like Sawtooth, Big Mouth and Red Piranha. Under the right conditions, flytraps—which usually retail for about $5 apiece—are easy to raise and can be reproduced through tissue culture or planting seeds.

One afternoon Luken and I drove to Supply, North Carolina, to visit the Fly-Trap Farm, a commercial greenhouse specializing in carnivorous plants. The office manager, whose name was Audrey (of all things) Sigmon, explained they had some 10,000 flytraps on hand. There’s a constant demand, she said, from garden clubs, graduating high-school seniors who’d rather receive flytraps than roses, and drama departments performing the musical version of Little Shop of Horrors for the millionth time.

Some of the nursery’s plants come from local harvesters who legally gather the plants, says Cindy Evans, another manager. But these days most of their flytraps come to North Carolina by way of the Netherlands and South America, where they are cultured and grown.

Imported houseplants won’t save the species in the wild. “You can’t rely on somebody’s greenhouse—those plants don’t have an evolutionary future,” says Don Waller, a University of Wisconsin botanist who has studied the plant’s ecology. “Once any plant is brought into cultivation, you have a system where artificial selection is replacing natural selection.”

As far as Luken can tell, wild flytraps are finding a few footholds in a tamer world. They thrive on the edge of some established ditches, a man-made niche that nonetheless mimics the wet-to-dry soil transition of natural bogs. The plants also prosper in power-line corridors, which are frequently mowed, mimicking the effects of fire. Luken, who has developed something like a sixth sense for their preferred habitat, has experimented with scattering their tiny black seeds in flytrappy spots, like the Johnny Appleseed of carnivorous plants. He’s even planted a couple near the entrance of his own subdivision, where they seem to be flourishing.

Staff writer Abigail Tucker has covered lions, narwhals and gelada monkeys. Lynda Richardson has photographed Smithsonian stories about Jamestown, Cuba and desert tortoises.