Ode to the Bubble

The Bell 47, famous as the star of “Whirlybirds,” was the DC-3 of helicopters. Could it make a comeback?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/cb/6dcb2e5e-1b2c-4522-9e9c-5b7b27b62530/03d_on12_bell47gfranksteinkohl01_live.jpg)

Summer’s end for me always meant a trip to the Wisconsin State Fair. After the obligatory meandering through the farm animal barns, my brothers and I would line up to commit mayhem in the bumper cars. But in 1967, when I was 10, as my brothers were giving each other whiplash, I schemed for something better. For an hour, I pestered my mother until she surrendered the five bucks I needed for a helicopter ride. Then I sprinted to the Bubble.

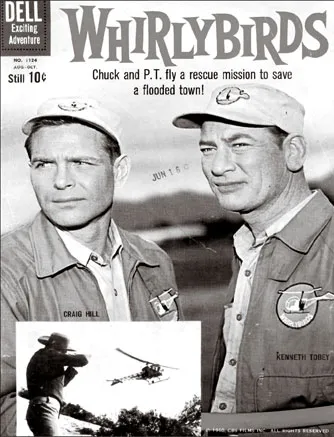

The Bell 47G at the fairgrounds was the exact type flown in the popular 1950s television series “Whirlybirds,” which I had watched in reruns on Saturday mornings: bubble cockpit, open-lattice tail boom, two-blade main rotor beating its signature whup whup whup. I strapped in for 10 minutes of magic and the bragging rights I’d exercise when school resumed. Hundreds of pilots are enjoying those same rights today, having found a way in adulthood to live their childhood dream.

As a kid, Joey Rhodes was a “Whirlybirds” fan. He bought his first Bubble in 1977 and today is the president and one of the founding members of the Bell 47 Helicopter Association. Since the group was founded in 2000, membership has grown from 11 to 700.

Tim Newton grew up on a farm in Stacyville, Iowa, up the road from a cropdusting operation that flew 47s. He’s been flying them for 17 years. Four years ago, he bought one to use for instruction and to give rides at county fairs, for $30 a seat. Dave James operates a fleet of 10 from his base in Wayne, Michigan, and hits the county fair circuit too. Jerry Clemens’ father crop-dusted in a 47. Today Clemens and his family operate Bell47parts.com, one of the largest independent suppliers of parts for the aircraft, out of Parsons, Kansas.

Jim Freeman runs Helicopter Specialties, a repair and refurbishment business for mostly turbine medevac helicopters, in Janesville, Wisconsin, but his personal helicopter is a 1955 Bell 47G2 that was once owned by William Boeing Jr.

The Bell 47 was the world’s first certified civil helicopter, the first to be used by all branches of the U.S. armed forces, to cross the Alps, to carry a U.S. president, and to spray crops—a job it does today. NASA used the 47 as a lunar module training aid for Apollo astronauts. But those distinctions have little to do with the loyalty the Bubble inspires.

“I’ve been flying for 35 years and I have yet to find another aircraft that can take the pounding these can take,” says Scott Churchill.

Churchill’s company, Scott’s Helicopter Services in Le Sueur, Minnesota, operates 20 Bell 47s, the world’s largest fleet. In addition to the crop-dusting operation he manages with his own 47s, Churchill has operated a Bell-authorized service center since 1990, and along the way became the de facto product support hotline for 47 operators worldwide. In 2010, he acquired the aircraft’s type certificate from Bell and formed a new company, Scott’s Bell 47, to support the aircraft. He hopes to place the helicopter back into production one day. For now, he and his supplier partners are developing new components, including more comfortable seats, a redesigned instrument panel, composite main rotor blades with longer lifespans, and canopies tinted to reduce sun glare.

Of 6,632 47s built by Bell and its foreign licensees, almost 700 still fly in the United States and 1,000 fly worldwide. The 47 has remained in service longer than any other helicopter. Why is it still popular?

“Simplicity,” says Roger Connor, curator of rotary flight at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. “The 47’s rotor system was lighter, much easier to maintain, more reliable and rugged than the Sikorsky articulated system.” The Sikorsky helicopters that entered service in the 1940s had three blades that were hinged to move forward and backward (lead and lag) as well as up and down (flapping). “There were six different hinges and a lot of movement,” says Connor. The 47 has a two-blade teetering, or seesaw, rotor system with two up-and-down hinges. “The 47’s mechanical simplicity allowed operating costs at about 50 percent of the [1945] Sikorsky S-51, but with much of the useful load.”

Churchill says the 47’s simplicity actually perplexes today’s generation of helicopter mechanics, who have been trained on complex turbine engine models. “Mechanics who were trained to work on [Sikorsky] Army Blackhawks can’t believe how simple 47s are to work on. If you see a crack on the airframe, you just weld it. The engines [piston Franklins and Lycomings] are out in the open and easy to fix.”

Most of the Bell operators use the 47 as they would a tractor or other piece of farm machinery. “A lot of other manufacturers are faster or prettier,” says Dave James, “but when it comes to being out in the field doing a job, nothing beats a 47.”

Empty, the 47G-2, one of the most popular variants, weighs about 1,400 pounds. It can carry about 1,100 pounds in passengers, cargo, and fuel for 255 miles at a pokey 80 mph (about 70 knots). Top speed is just north of 95. Jerry Clemens of Bell47parts.com says the helicopter’s robustness makes it an ideal trainer. “If you make a hard landing in a 47, you bend the cross tube section and it costs you $800, not $20,000.”

Its near invincibility also won Bell a famous customer. Roger Connor notes that in 1957 President Dwight Eisenhower’s pilot chose the Bell 47J (H-13J, in military service) for the first Presidential helicopter over much more capable models. During its first decade of service, the Bubble had built a reputation for safety and reliability. “That turned out to be a bad decision,” he adds. “Eisenhower dumped the 47J pretty fast. He could bring along only a Secret Service agent, and his aides, who were traveling in Sikorskys, got there faster than he did. And of course the bubble cooked him alive.” The faster, roomier Sikorsky H-34 took over the job of presidential transport.

Scott Churchill admits that the cockpit can get pretty warm. “In the summer it is like sitting in a sauna,” he says. “And then you put the helmet on and it’s like you put a microwave over your head and plugged it in.” The small engine can’t spare excess power for air-conditioning, so most pilots fly with the doors off in summer.

The bubble makes the cockpit warm, but it also gives pilot and passenger a panoramic view of the landscape, as I found when I hopped a ride with Churchill at his Minnesota base. After we lifted off and circled the field, Churchill chopped the power and put us into a practice autorotation, an emergency landing maneuver that my stomach thought was an uncontrolled plunge down an elevator shaft. The ground started coming up real fast, and in the Bubble, you can see all of it. Churchill aimed for an open spot and flared to a gentle touchdown. “Bell designed [the 47] with a nice rotor system that is very forgiving,” he said, reassuringly. “Let’s try another one.”

I reminded myself what Churchill told me about his pilots, who fly up to 12 hours a shift: They make as many as 60 takeoffs and landings a day.

Despite the heat in the cockpit and its stately pace, the Bubble has become a classic, and, as often happens in aviation, its fans treasure it for sentimental as well as practical reasons. Says Scott’s Helicopter Services chief pilot Mike Balch: “People look at this helicopter the same way [fixed-wing pilots] look at a Stearman or a J-3 Cub.”

The designer of the Bell 47 was not an aeronautical engineer but a mathematician and philosopher who believed the act of inventing would help him understand the workings of the universe. Arthur Young graduated from Princeton University with a degree in mathematics and set about tackling the problem of providing stability in vertical flight. After some experimentation, he conceived a system in the late 1930s that linked a two-blade main rotor to a stabilizer bar, mounted on a mast beneath the rotor blades. The weighted, spinning bar acted as a gyroscope to help the rotor resist change in its plane of rotation, thus dampening the effects of wind gusts and other perturbations. Young patented the design in 1937 and later assigned the patent to the Bell Aircraft Company when he joined the company to build technology demonstrators and a series of Model 30 prototypes. Devotees claim the helicopter should really be called the “Young 47.”

The first was built in an abandoned Chrysler dealership in a suburb of Buffalo, New York, in late 1942. Two years later, a Bell Model 30 made its public debut before a crowd of 42,000 at a soldiers’ benefit show inside Buffalo’s sports stadium. (This model is now on display at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virgnia.) In 1946, its descendant Model 47 earned certification from the Civil Aeronautics Administration, a forerunner of the Federal Aviation Administration. Looking back, Joey Rhodes thinks it remarkable that the helicopter was built at all as Young and Bell Aircraft president Larry Bell disagreed on a key point.

“Larry Bell wanted his helicopters to look like cars,” Rhodes says. “Young was more interested in the smoothness and safety of the helicopter.” In the end, it was Young’s concept of the 47D, with the plexiglass bubble, as opposed to Bell’s preference—a design that looked like a family sedan—that won out. Both versions appeared at the 1947 National Aircraft Show in Cleveland, Ohio. At the show, Bell sold 27 Bubbles and exactly none of the sedans.

Larry Bell died of a stroke at 62 in 1956, and his company was subsequently sold to Textron; Arthur Young left aviation in 1947, published several books on philosophy, and went on to found the Institute for the Study of Consciousness in Berkeley, California. He died there in 1995 at the age of 89.

Although World War II was over by the time the Bubble was certified, the war influenced the 47’s development. The late-1940s bust in the aviation industry left a scarcity of resources to develop new parts, and the war’s end had left airplane makers with big stockpiles of fixed-wing military aircraft parts. (During the war, Bell built the P-39 Airacobra, the P-63 Kingcobra, and the first U.S. jet, the P-59 Airacomet.) According to Scott Churchill, all those leftovers played pivotal roles in the design and manufacture of the 47. “It was developed from World War II surplus parts that came off the shelves or fixed-wing aircraft after the war,” he says. “They were proven parts. The universal joint on the tail boom was the same one used on wing flaps on World War II fighters. The swashplate [a device used to provide pitch control of the main rotor blades] used off-the-shelf bearings; they didn’t design the part for a new bearing. Little things like that kept the cost down. It is sort of like a farm tractor: You can buy a new bearing for it anywhere. That’s how they wanted to build it.”

As the Korean War ramped up in 1950, one thing Larry Bell had a big supply of were 200-horsepower Franklin O335-3 engines for a military version of the 47, designated the H-13. Initially, H-13s were used as scout aircraft, but once in the battlefield, pilots began adapting them to other missions, including medevac. On January 3, 1951, Lieutenants Willie Strawn and Joe Bowler, both in H-13s, flew Army medevac missions with skid-mounted litters improvised by Army Captain Albert Sebourn. But those missions were not the first medevacs of the Korean War. The Marines of VMO-6 beat the Army by less than a week, also flying the Bell H-13 (designated HTL-4).

By the time of the 1953 armistice, according to the National Air and Space Museum’s Roger Connor, almost 40,000 wounded troops had been evacuated by helicopter, more than half in H-13s.

After the war, the services ordered 1,500 model 47 variants as primary and instrument trainers as well as gunships. However, it was the helicopter’s Korean War performance that made it a legend. The dramatization of its work as an aerial ambulance, in both the 1970 movie M*A*S*H and the subsequent television series, made the H-13/47 the world’s most recognized helicopter. Each of the television show’s 251 episodes, which ran from 1972 to 1983, opened with a pair of Bell H-13s carrying wounded soldiers on side-mounted stretchers and landing at the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital. The Bubble’s effect on two generations was the work of one director: Robert Altman, who directed the film version of M*A*S*H, had years earlier directed episodes of “Whirlybirds.”

Although Model 47 variants would fly in the Vietnam War, by then the Army preferred Bell’s new turbine-powered models, the UH-1 Huey and the Hughes OH-6 Cayuse. In the civilian market, Bell introduced the Model 206 JetRanger in 1967. The debut of the 206 marked the beginning of the end of the 47. After Bell ended 47 production in 1974, the company continued to support the helicopter, but spare parts became increasingly expensive. Operators of the piston-powered relic came to believe that it was a nuisance to the company.

“A lot of people were falling out of love with Bell Helicopter,” says Joey Rhodes.

As the animus between Bell and the 47 community grew, a handful of operators decided to take action. In 2000, led by Jack Kelly and Charlie Hollinger, they formed the Bell 47 Helicopter Association. Rhodes says the group’s immediate goal was to “form a new relationship with Bell Helicopter because the old one was in the gutter.” Bell assigned 47 guru Don Maguire to work with them.

Today the director of customer support for Scott’s Bell 47, Maguire explains Bell Helicopter’s predicament at the time the association was formed. “Nobody is in the business to build parts to put them on the shelf,” he says, and since operators often considered Bell the supplier of last resort, there were times when the company sold one part in a year. “If a part is a high-volume sale item, the manufacturer can stock it, and the cost is minimized.” In addition, Bell’s position at the time, says Maguire, is the same as Scott’s Bell 47’s position today: Helicopters that were once in military service and their parts are ineligible for civilian certification and therefore unsupportable. The Bell 47 Helicopter Association, says Joey Rhodes, takes the same stand.

One of the association’s first tasks was to stem the stream of bogus 47 parts coming onto the market. Most of these had been stripped from decommissioned military helicopters and, at the very least, lacked the proper documentation to be used legally on civil 47s. An undocumented part could have been flown longer than its specified life, Rhodes says, and could pose a real danger.

Just as the association was solving that problem, the FAA issued an emergency airworthiness directive that threatened to ground 75 percent of the U.S.-based 47 fleet—possibly for good.

On the morning of August 13, 1998, a Bell 47G-2 cropdusting near Windsor, Ontario, crashed. Canada’s Transportation Safety Board investigating the accident found that one of the main rotor blades had separated in flight because a grip connecting it to the drive shaft and hub had failed. Based on that report, the U.S. FAA mandated on August 31, 2000, an inspection of the 47’s main rotor blade grips every 200 flight hours and their replacement after 1,200 flight hours. Each grip inspection was estimated to cost at least $2,000; a new set of grips, $7,200. This for a helicopter that was then worth less than $80,000, flown by operators who worked at razor-thin profit margins. With the imposition of a 1,200-hour lifetime, three-quarters of the fleet was out of compliance overnight, and Bell had nowhere near enough new grips to sell to the affected owners. The FAA’s rotorcraft directorate was swamped by requests from operators for approved Alternate Means of Compliance; they petitioned to keep flying while they waited for grips. Meanwhile, the Experimental Aircraft Association led an industry coalition that eventually persuaded the FAA to relax the new restrictions, but not until mid-2001. “If it hadn’t been for the EAA, most Bell 47s would have stayed grounded because of a very isolated event in Canada,” says Rhodes.

According to Don Maguire, who was with Bell Helicopter at the time, the company’s position was that the grip in Canada had failed because of improper maintenance and that the part is capable of a 2,500-hour life.

At the time of the grip airworthiness directive, several independent companies gained FAA Parts Manufacturing Approval for the 47’s components, including the blade grips, and the gap between Bell’s prices for parts and those of aftermarket companies continued to widen. Operators viewed the price Bell wanted for a single metal main rotor blade as a threat to the 47’s continued viability. Overnight, it jumped from $48,000 to $170,000. At the new price, it exceeded the value of the helicopter.

Says Scott Churchill: “They didn’t sell any at that price—no surprise.”

Though Bell’s Don Maguire continued to offer technical support to operators, Bell also asked Churchill to take their calls, since his company was now manufacturing parts that Bell was no longer making. Churchill drew on what he’d learned in running a Bell-authorized service center for 20 years.

In 2003, he began talking to the leadership of Bell about acquiring the license to produce more of the Model 47, and in 2010, Bell’s CEO, John Garrison, agreed to transfer the type certificate. Churchill hired Neil Marshall, who previously worked at Bell as program director for the new Model 429 light turbine twin, to run Scott’s Bell 47. Last year the company moved into a refurbished building near Churchill’s Le Sueur, Minnesota base to house the project.

Marshall’s immediate priorities are to negotiate a serial production engine deal with Lycoming, work with a new manufacturer to bring down the price of replacement main rotor blades, and build confidence in the supply chain. He also faces the challenge of converting more than 9,000 paper engineering drawings from the 1950s and 1960s to digital format; today’s suppliers only deal with digital drawings. But his ultimate goal is new production. From a recent survey of 47 operators, Marshall found that two-thirds would buy a brand-new 47 if it were available. “We are actively soliciting customers willing to put up a refundable deposit on delivery of a new Bell 47 from Scott’s,” says Don Maguire. He adds, “Bell has been incredibly supportive and is as committed to [the 47’s] success as we are. They invite us to participate in all the conferences they hold for their customers.” Joey Rhodes agrees that Bell is now honoring its first helicopter.

At a 2001 fly-in at La Verne, California, the Bell 47 Helicopter Association feted actor Ken Tobey, who starred as pilot Chuck Martin in “Whirlybirds.” Tobey died the following year, at 85. Joey Rhodes recalls that Tobey downplayed the accolades because he was not really a pilot; he just played one on TV. But the members assured him that to them he was a pilot and that many of the pilots in the room had learned to fly the 47 because of him.

At the Bell company’s academy in Fort Worth, Texas, where pilots and mechanics train on its turbine helicopters, managers hold a weekly drawing. The winner gets a coveted prize: a ride in the academy’s lone remaining Model 47.