The 175-Year History of Speculating About President James Buchanan’s Bachelorhood

Was his close friendship with William Rufus King just that, or was it evidence that he was the nation’s first gay chief executive?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/34/0a34af72-78cf-4745-8597-b1bcad2f9677/james-buchanan.jpg)

At the start of 1844, James Buchanan’s presidential aspirations were about to enter a world of trouble. A recent spat in the Washington Daily Globe had stirred his political rivals into full froth—Aaron Venable Brown of Tennessee was especially enraged. In a “confidential” letter to future first lady Sarah Polk, Brown savaged Buchanan and “his better half,” writing: “Mr. Buchanan looks gloomy & dissatisfied & so did his better half until a little private flattery & a certain newspaper puff which you doubtless noticed, excited hopes that by getting a divorce she might set up again in the world to some tolerable advantage.”

The problem, of course, is that James Buchanan, our nation’s only bachelor president, had no woman to call his “better half.” But, as Brown’s letter implies, there was a man who fit the bill.

Google James Buchanan and you inevitably discover the assertion that American history has declared him to be the first gay president. It doesn’t take much longer to discover that the popular understanding of James Buchanan as our nation’s first gay president derives from his relationship with one man in particular: William Rufus DeVane King of Alabama. The premise raises many questions: What was the real nature of their relationship? Was each man “gay,” or something else? And why do Americans seem fixated on making Buchanan our first gay president?

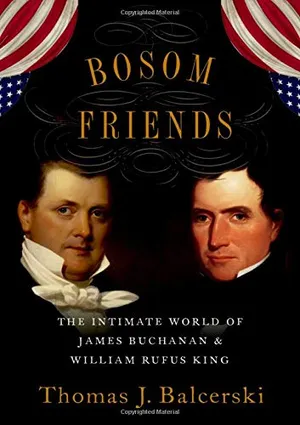

My new book, Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King, aims to answer these questions and set the record straight, so to speak, about the pair. My research led me to archives in 21 states, the District of Columbia, and even the British Library in London. My findings suggest that theirs was an intimate male friendship of the kind common in 19th-century America. A generation of scholarship has uncovered numerous such intimate and mostly platonic friendships among men (though some of these friendships certainly included an erotic element as well). In the years before the Civil War, friendships among politicians provided an especially important way to bridge the chasm between the North and the South. Simply put, friendships provided the political glue that bound together a nation on the precipice of secession.

This understanding of male friendship pays close attention to the historical context of the time, an exercise that requires one to read the sources judiciously. In the rush to make new meaning of the past, I have come to understand why today it has become de rigeur to consider Buchanan our first gay president. Simply put, the characterization underscores a powerful force at work in historical scholarship: the search for a usable queer past.

Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King

While exploring a same-sex relationship that powerfully shaped national events in the antebellum era, Bosom Friends demonstrates that intimate male friendships among politicians were—and continue to be—an important part of success in American politics

The year was 1834, and Buchanan and King were serving in the United States Senate. They came from different parts of the country: Buchanan was a lifelong Pennsylvanian, and King was a North Carolina transplant who helped found the city of Selma, Alabama. They came by their politics differently. Buchanan started out as a pro-bank, pro-tariff, and anti-war Federalist, and held onto these views well after the party had run its course. King was a Jeffersonian Democrat, or Democratic-Republican, who held a lifelong disdain for the national bank, was opposed to tariffs, and supported the War of 1812. By the 1830s, both men had been pulled into the political orbit of Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party.

They soon shared similar views on slavery, the most divisive issue of the day. Although he came from the North, Buchanan saw that the viability of the Democratic Party depended on the continuance of the South’s slave-driven economy. From King, he learned the political value of allowing the “peculiar institution” to grow unchecked. Both men equally detested abolitionists. Critics labeled Buchanan a “doughface” (a northern man with southern principles), but he pressed onward, quietly building support across the country in the hopes of one day rising to the presidency. By the time of his election to that office in 1856, Buchanan was a staunch conservative, committed to what he saw as upholding the Constitution and unwilling to quash southern secession during the winter of 1860 to 1861. He had become the consummate northern doughface.

King, for his part, was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1810. He believed in states’ rights, greater access to public lands, and making a profit planting cotton. His commitment to the racial hierarchy of the slaveholding South was whole cloth. At the same time, King supported the continuation of the Union and resisted talk of secession by radical Southerners, marking him as a political moderate in the Deep South. For his lifelong loyalty to the party and to balance the ticket, he was selected as the vice-presidential running mate under Franklin Pierce in 1852.

Buchanan and King shared one other essential quality in addition to their political identification. Both were bachelors, having never married. Born on the Pennsylvania frontier, Buchanan attended Dickinson College and studied law in the bustling city of Lancaster. His practice prospered nicely. In 1819, when he was considered to be the city’s most eligible bachelor, Buchanan became engaged to Ann Coleman, the 23-year-old daughter of a wealthy iron magnate. But when the strain of work caused Buchanan to neglect his betrothed, Coleman broke off the engagement, and she died shortly thereafter of what her physician described as “hysterical convulsions.” Rumors that she had committed suicide, all the same, have persisted. For Buchanan’s part, he later claimed that he entered politics as “a distraction from my great grief.”

The love life of William Rufus DeVane King, or “Colonel King” as he was often addressed, is a different story. Unlike Buchanan, King was never known to pursue a woman seriously. But—critically—he could also tell a story of a love lost. In 1817, while serving as secretary to the American mission to Russia, he supposedly fell in love with Princess Charlotte of Prussia, who was just then to marry Czar Nicholas Alexander, heir to the Russian imperial throne. As the King family tradition has it, he passionately kissed the hand of the czarina, a risky move that could have landed him in serious jeopardy. The contretemps proved fleeting, as a kind note the next day revealed that all was forgiven. Still, he spent the remainder of his days bemoaning a “wayward heart” that could not love again.

Each of these two middle-aged bachelor Democrats, Buchanan and King, had what the other lacked. King exuded social polish and congeniality. He was noted for being “brave and chivalrous” by contemporaries. His mannerisms could at times be bizarre, and some thought him effeminate. Buchanan, by contrast, was liked by almost everyone. He was witty and enjoyed tippling, especially glasses of fine Madeira, with fellow congressmen. Whereas King could be reserved, Buchanan was boisterous and outgoing. Together, they made for something of an odd couple out and about the capital.

While in Washington, they lived together in a communal boardinghouse, or mess. To start, their boardinghouse included other congressmen, most of whom were also unmarried, yielding a friendly moniker for their home: the “Bachelor’s Mess.” Over time, as other members of the group lost their seats in Congress, the mess dwindled in size from four to three to just two—Buchanan and King. Washington society began to take notice, too. “Mr. Buchanan and his Wife,” one tongue wagged. They were each called “Aunt Nancy” or “Aunt Fancy.” Years later, Julia Gardiner Tyler, the much younger wife of President John Tyler, remembered them as “the Siamese twins,” after the famous conjoined twins, Chang and Eng Bunker.

Certainly, they cherished their friendship with one another, as did members of their immediate families. At Wheatland, Buchanan’s country estate near Lancaster, he hung portraits of both William Rufus King and King’s niece Catherine Margaret Ellis. After Buchanan’s death in 1868, his niece, Harriet Lane Johnston, who played the part of first lady in Buchanan’s White House, corresponded with Ellis about retrieving their uncles’ correspondence from Alabama.

More than 60 personal letters still survive, including several that contain expressions of the most intimate kind. Unfortunately, we can read only one side of the correspondence (letters from King to Buchanan). One popular misconception holds that their nieces destroyed their uncles’ letters by pre-arrangement, but the real reasons for the mismatch stem from multiple factors: for one, the King family plantation was raided during the Battle of Selma in 1865, and for another, flooding of the Selma River likely destroyed portions of King’s papers prior to their deposit at the Alabama Department of Archives and History. Finally, King dutifully followed Buchanan’s instructions and destroyed numerous letters marked “private” or “confidential.” The end result is that relatively few letters of any kind survive in the various papers of William Rufus King, and even fewer have ever been prepared for publication.

By contrast, Buchanan kept nearly every letter which he ever received, carefully docketing the date of his response on the backside of his correspondence. After his death, Johnston took charge of her uncle’s papers and supported the publication of a two-volume set in the 1880s and another, more extensive 12-volume edition in the early 1900s. Such private efforts were vital to securing the historical legacy of U.S. presidents in the era before they received official library designation from the National Archives.

Still, almost nothing written by Buchanan about King remains available to historians. An important exception is a singular letter from Buchanan written to Cornelia Van Ness Roosevelt, wife of former congressman John J. Roosevelt of New York City. Weeks earlier, King had left Washington for New York, staying with the Roosevelts, to prepare for a trip overseas. In the letter, Buchanan writes of his desire to be with the Roosevelts and with King:

I envy Colonel King the pleasure of meeting you & would give any thing in reason to be of the party for a single week. I am now “solitary & alone,” having no companion in the house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them. I feel that it is not good for man to be alone; and should not be astonished to find myself married to some old maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for me when I am well & not expect from me any very ardent or romantic affection.

Along with other select lines of their correspondence, historians and biographers have interpreted this passage to imply a sexual relationship between them. The earliest biographers of James Buchanan, writing in the staid Victorian era, said very little about his sexuality. Later Buchanan biographers from the 1920s to the 1960s, following the contemporary gossip in private letters, noted that the pair were referred to as “the Siamese twins.”

But by then, an understanding of homosexuality as a sexual identity and orientation had begun to take hold among the general public. In the 1980s, historians rediscovered the Buchanan-King relationship and, for the first time, explicitly argued that it may have contained a sexual element. The media soon caught wind of the idea that we may have had a “gay president.” In the November 1987 issue of Penthouse Magazine, New York gossip columnist Sharon Churcher noted the finding in an article headlined “Our First Gay President, Out of the Closet, Finally.” The famous author—and Pennsylvania native—John Updike pushed back somewhat in his novel Memories of the Ford Administration (1992). Updike creatively imagined the boardinghouse life of Buchanan and King, but he admitted to finding few “traces of homosexual passion.” Updike’s conclusion has not stopped a veritable torrent of historical speculation in the years since.

This leaves us today with the popular conception of James Buchanan as our first gay president. On the one hand, it’s not so bad a thing. Centuries of repression of homosexuality in the United States has erased countless number of Americans from the story of LGBT history. The dearth of clearly identifiable LGBT political leaders from the past, moreover, has yielded a necessary rethinking of the historical record and has inspired historians to ask important, searing questions. In the process, past political leaders who for one reason or another don’t fit into a normative pattern of heterosexual marriage have become, almost reflexively, queer. More than anything else, this impulse explains why Americans have transformed James Buchanan into our first gay president.

Certainly, the quest for a usable queer past has yielded much good. Yet the specifics of this case actually obscure a more interesting, and perhaps more significant, historical truth: an intimate male friendship between bachelor Democrats shaped the course of the party, and by extension, the nation. Worse still, moving Buchanan and King from friends to lovers blocks the way for a person today to assume the proper mantle of becoming our first gay president. Until that inevitable day comes to pass, these two bachelors from the antebellum past may be the next closest thing.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.