A 1911 Report Set America On a Path of Screening Out ‘Undesirable’ Immigrants

The Dillingham Commission conducted one of the most extensive investigations on immigration to the U.S. But in the end, bias hijacked its recommendations

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/86/e18681ad-8913-46c0-a6c0-0a8f7fe176ab/zeidel-lead.png)

The Dillingham Commission is today little known. But a century ago, it stood at the center of a transformation in immigration policy, exemplifying Americans’ simultaneous feelings of fascination and fear toward the millions of migrants who have made the United States their home.

In 1911, the Dillingham Commission produced perhaps the most extensive investigation of immigration in the history of the country, an exhaustive 41-volume study that demonstrated just how vital 19th-century and early-20th-century immigrants were to the U.S. economy. But the commission’s own recommendations, delivered in the context of a fierce backlash against migrants, set the foundation for the end of industrial-era immigration and a half-century of exclusionist policies.

Congress created the Commission in 1907 in an effort to find a compromise between proponents and opponents of immigration. During the previous several decades, pundits and lawmakers had debated the need to impose restrictions on immigration. Lawmakers enacted several polices intended to interdict those deemed to pose a specific danger, such as people afflicted with contagious diseases or involved in moral turpitude. One notable act excluded Chinese laborers, and another prohibited the entry of workers who had been hired overseas by U.S. companies.

But critics dismissed these provisions as insufficient, and instead sought laws to reduce the overall number of entrants and improve their quality, the latter of which meant attributes, like literacy, that were perceived to make it easier for newcomers to assimilate and contribute to the nation.

The literacy test, a requirement that most adult immigrants be able to read or write, became the preferred restriction. Supporters saw it as the best means of securing the “most desirable” migrants, while critics saw education as the product of opportunity, not character or potential. In 1907, when Congress could not agree on its propriety, it created the Dillingham Commission—named for its chairman, U.S. Sen. William P. Dillingham, a Vermont Republican.

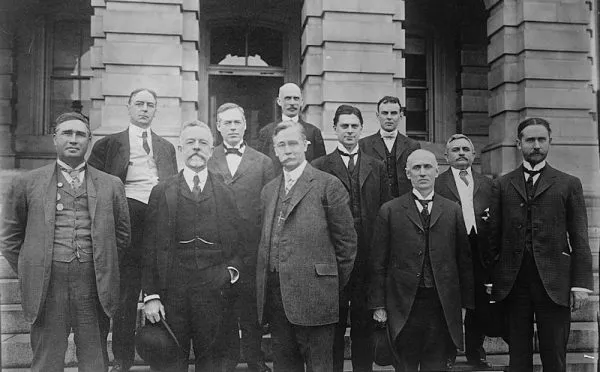

Over the next three years, the nine-member commission—comprising three U.S. senators, three representatives, and three “experts” selected by President Theodore Roosevelt—fulfilled its charge by conducting a thorough and wide-ranging investigation of current and past immigration. Its multi-volume Reports is a treasure trove of information that remains profoundly useful to students of immigration today.

Most of the work centered on “Immigrants in Industry,” but other topics of inquiry included “Immigrants in Cities,” “Children of Immigrants in Schools,” and a study of changes in immigrant physiology, the last conducted by anthropologist Franz Boas. He and his associates took head, or cranium, measurements of immigrant children in schools and concluded that the U.S. environment was engendering positive changes in “bodily form.” The children had features less like their European counterparts and more like “American types.” Commissioner Jeremiah Jenks also prepared a controversial Dictionary of Races, in which he sought definitively to identify and characterize the world’s races—or ethnic groups.

But it was not these reports that made the most impact. The commission also produced a compendium to summarize its findings and make policy recommendations. The latter would have profound effects.

The commissioners based their recommendations on the principle of admitting immigrants of such “quantity and quality as not to make too difficult the process of assimilation.” This, they acknowledged, constituted a departure from America’s traditional welcome of “the oppressed of other lands.” A corollary called for basing admission standards on “the prosperity and economic well-being of our people.” This raised the question of which polices would produce the desired effect. The recommended literacy test, argued racial theorist Madison Grant, would exclude low-quality individuals lacking in social, physical, and mental capabilities and who added nothing of value to America’s moral or intellectual character. Others saw it excluding too many of the hard-working manual laborers who had forged America’s steel and built its railroads.

After intense debate, the commission recommended passage of the literacy test, calling it “the single most feasible” method of exclusion. Restrictionists viewed this as an endorsement of their cause and used the recommendation to secure the test’s eventual passage by Congress in 1917.

The Reports also mentioned several other possible means of restriction that could warrant future consideration. These included the “limitation of the number of each race arriving each year to a certain percentage of that race arriving during a given period of years.” At the time, “race” was often equated to the modern meaning of ethnicity and sometimes drew its terminology from nationality, such as references to the “German race.” But, Jews were considered a distinctive race, subsumed within various nation-states.

William W. Husband, the Commission’s chief administrator, thereafter developed a quota scheme based on the 1910 census. Admission of immigrants belonging to a particular nationality would be limited to 5 percent of their total as reported in the census. Congress reduced that percentage to 3 in its temporary quota measure, passed in 1921. The permanent measure, passed in 1924, lowered it to 2 percent and used the 1890 census as the benchmark. The changes were deliberately designed to exclude more southern and eastern Europeans, so-called new immigrants deemed “undesirable” by many contemporary Americans. Asians, deemed wholly “undesirable,” did not receive any quotas. (Intriguingly, the Quota Acts exempted immigrants from the Western Hemisphere.) These provisions would define American immigration policy until passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965.

The experience and impact of the Dillingham Commission offers lasting lessons to a country that still argues about immigration. The chief one is that fear tends to override facts about immigration policy, even when facts are in abundance.

Throughout its inquiry, the commission’s investigators sought to maintain objectivity; to collect the facts, let them speak for themselves, and make recommendations absent of bias. Throughout the Reports, the commission described immigrants positively, including the vilified “new” arrivals. Even the verbiage immediately preceding the recommendation of the literacy test spoke of them positively.

Yet, a social climate of fear and bigotry hijacked the investigation, and the commissioners themselves, ignoring facts in their own reports, endorsed restriction, largely to exclude the most recent types of immigrants. Critics, to no avail, would argue that socioeconomic conditions did not warrant more extensive exclusion, based on the commission’s own standards for such action. But the commission’s identification of the literacy test as the most “feasible method” trumped any such assertions.

So, too, when William Husband drafted his initial quota proposal, he based it on much more generous terms than did the congressmen who approved the final version. He also included quotas that would admit people from Asian countries—but the final versions in the quota laws had none, as bigoted extremism carried the day. The United States would enforce an Asian Exclusion Zone until the 1950s, and then establish only minuscule Asian quotas.