1927 Magazine Looks at Metropolis, “A Movie Based On Science”

How filmmakers created a gorgeous, dystopian future

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/64/31642bc8-f628-4dc1-8b40-76766855eb90/1927-june-science-metropolis-1.jpeg)

Last week Geeta Dayal over at Wired published portions of a very cool 32-page program for the 1927 futuristic film Metropolis. The program is for sale at a rare book shop in London and seeing the blog post reminded me of an article in one of my magazines from 1927. It took me a little while to find (most of my archive is a terribly disorganized mess) but I finally found the magazine I was looking for — the June 1927 issue of Science and Invention.

The magazine featured a two-page spread titled, ”Metropolis—A Movie Based On Science,” with photographs and illustrations depicting how the movie’s cutting-edge effects were achieved. The use of miniatures, sparks of electricity with forced perspective and television-telephones are all explained in illustrations credited to “Bate.”

The creation of Metropolis and its many versions is a fascinating story. Director Fritz Lang‘s original cut of Metropolis was a financial flop and appeared in German theaters for only four months before it was pulled and recut. The film premiered in Germany but was actually released to American theaters before it received a wide German release. Strangely, American audiences never saw Fritz Lang’s edit of the film, since Paramount (the film’s American distributor) preemptively edited their version of the film. If you get a chance, I highly recommend that you check out the 2010 documentary Voyage to Metropolis, about the many different versions of this film and its ultimate restoration in 2008 to an “original” version after the discovery of an old 16mm version of the film in Buenos Aires. The Buenos Aires version is believed to be the closest to the original, with over 25 minutes more than any previously known edit, and Metropolis was released theatrically in 2010 with these additional (if badly scratched) scenes added. I got to see the new cut two summers ago when it screened in Minneapolis and it really is gorgeous.

Just as different versions of this film are constantly resurfacing all around the world, I suspect different promotional materials — be they programs, magazines articles or movie posters — will continue to captivate historians and film fans hoping to learn more about how this classic piece of futurism was originally filmed and promoted. In the case of this Science and Invention article the film was promoted to an audience interested in how science would be used in movie effects of the future.

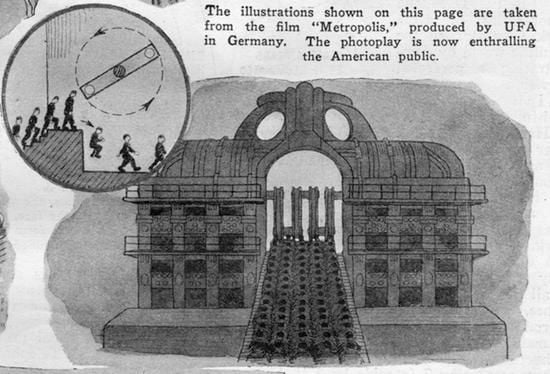

The illustration above, which shows the use of miniatures in the Metropolis city of tomorrow, is explained in the magazine spread:

The miniature set which was used in the filming of this remarkable motion picture. Toy trains and automobiles were pulled along the bridges by means of wires. The airplanes were suspended by a wire which was pulled by an operator outside of the set. At times full size lower stories were used, the image of the upper stories being reflected in a mirror to blend with them.

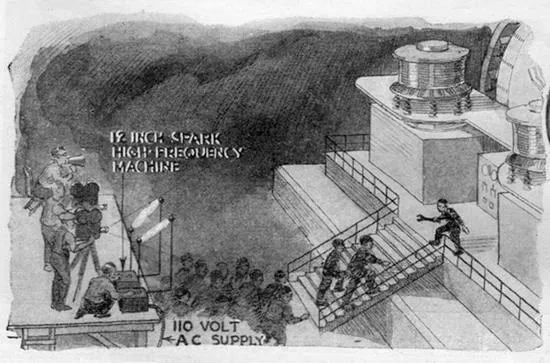

The magazine explained right down to the voltage how sparks were produced, creating a dystopian atmosphere for those working. In order to make the giant coils on the right appear to have sparks jumping between them, forced perspective was used with the sparks little more than a couple of feet in front of the camera.

The effect of sparks jumping about the machines was produced by placing a small high frequency apparatus near the camera as shown above. In the finished picture the sparks seemed to jump from the two huge coils placed on either side of the mechanism.

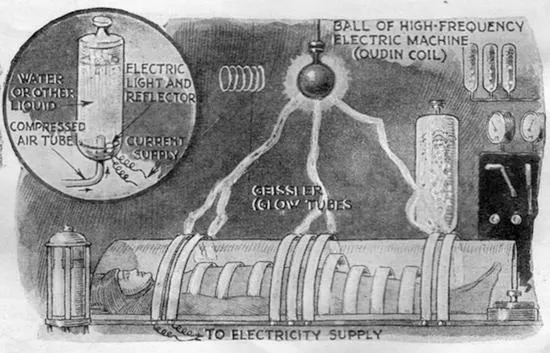

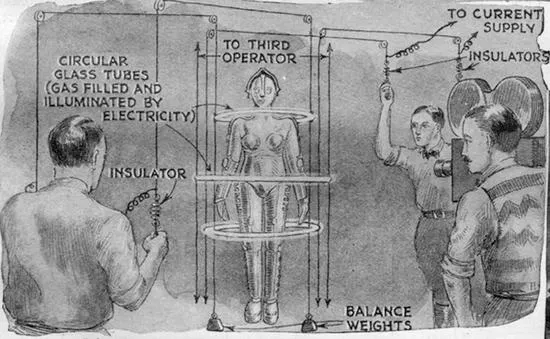

The illustration above explains how the magnificent glowing effects were produced using electricity and Geissler tubes.

The spectacular scene in the scientist’s laboratory. A weird effect was obtained by forcing compressed air through a closed tube containing liquid and illuminated by a lamp placed at the bottom.

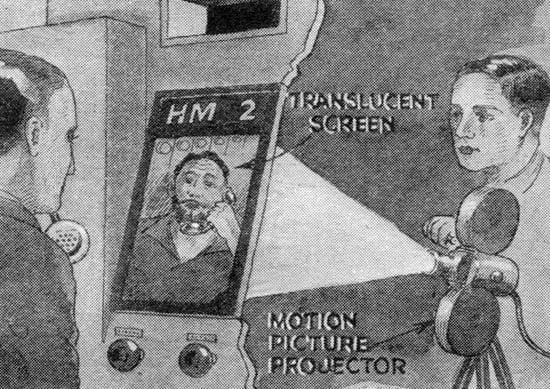

Also discussed is the television phone. As the illustration above shows, a movie projector is used to make it appear as if two people are having a conversation. We’ve looked at the evolving definition of television many times on this blog, and it’s interesting to see that this article uses the term “television apparatus,” without mentioning the word telephone once. Before television was ever realized as a broadcast medium (and it would be decades after Metropolis was released), television was often envisioned as a point-to-point rather than broadcast technology.

Of course the city of the future would have all the inventions of which we dream today. The recently perfected television apparatus, is in common use. By using it, those who converse may also at the same time see the other party.

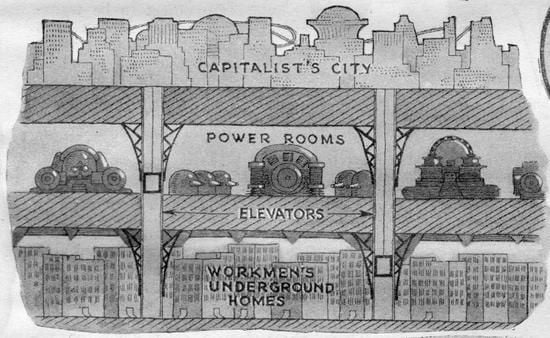

The illustration above shows, “A sectional view of ‘Metropolis,’ the city of the future,” with the Capitalist’s City above, power production rooms in the middle and the Workmen’s Underground Homes below.

The article illustrates how actors were moved through, “The maw of the huge machine which ruthlessly destroys body and soul.”

The illustration above shows how the “concentric rings of light which played about the manikin were hand operated” and gave the illusion that they were floating.

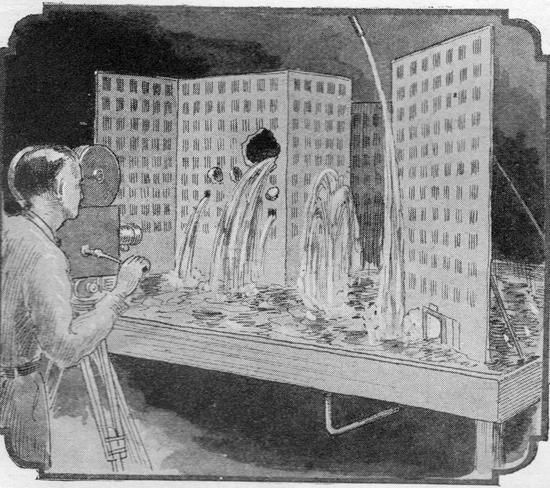

The last illustration in the two-page spread shows the destruction of the “Workman’s City,” which is again shot in miniature.

A small set was used and water, forced through pipes, was directed through the sides of the buildings and down from above. Pipes placed at street level ejected water in a geyser-like effect.

Aesthetically, Metropolis went on to influence countless other films about the future — from Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, to the design of the robot C3PO in the Star Wars franchise.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)