In 1945, a Japanese Balloon Bomb Killed Six Americans, Five of Them Children, in Oregon

The military kept the true story of their deaths, the only civilians to die at enemy hands on the U.S. mainland, under wraps

:focal(1439x257:1440x258)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/e9/23e98c5d-fc4a-4b55-bdf2-7aeeca893bc5/onpaperwingselsye1.jpg)

Elsye Mitchell almost didn’t go on the picnic that sunny day in Bly, Oregon. She had baked a chocolate cake the night before in anticipation of their outing, her sister would later recall, but the 26-year-old was pregnant with her first child and had been feeling unwell. On the morning of May 5, 1945, she decided she felt decent enough to join her husband, Rev. Archie Mitchell, and a group of Sunday school children from their tight-knit community as they set out for nearby Gearhart Mountain in southern Oregon. Against a scenic backdrop far removed from the war raging across the Pacific, Mitchell and five other children would become the first—and only—civilians to die by enemy weapons on the United States mainland during World War II.

While Archie parked their car, Elsye and the children stumbled upon a strange-looking object in the forest and shouted back to him. The reverend would later describe that tragic moment to local newspapers: “I…hurriedly called a warning to them, but it was too late. Just then there was a big explosion. I ran up – and they were all lying there dead.” Lost in an instant were his wife and unborn child, alongside Eddie Engen, 13, Jay Gifford, 13, Sherman Shoemaker, 11, Dick Patzke, 14, and Joan “Sis” Patzke, 13.

Dottie McGinnis, sister of Dick and Joan Patzke, later recalled to her daughter in a family memory book the shock of coming home to cars gathered in the driveway, and the devastating news that two of her siblings and friends from the community were gone. “I ran to one of the cars and asked is Dick dead? Or Joan dead? Is Jay dead? Is Eddie dead? Is Sherman dead? Archie and Elsye had taken them on a Sunday school picnic up on Gearhart Mountain. After each question they answered yes. At the end they all were dead except Archie.” Like most in the community, the Patzke family had no inkling that the dangers of war would reach their own backyard in rural Oregon.

But the eyewitness accounts of Archie Mitchell and others would not be widely known for weeks. In the aftermath of the explosion, the small, lumber milling community would bear the added burden of enforced silence. For Rev. Mitchell and the families of the children lost, the unique circumstances of their devastating loss would be shared by none and known by few.

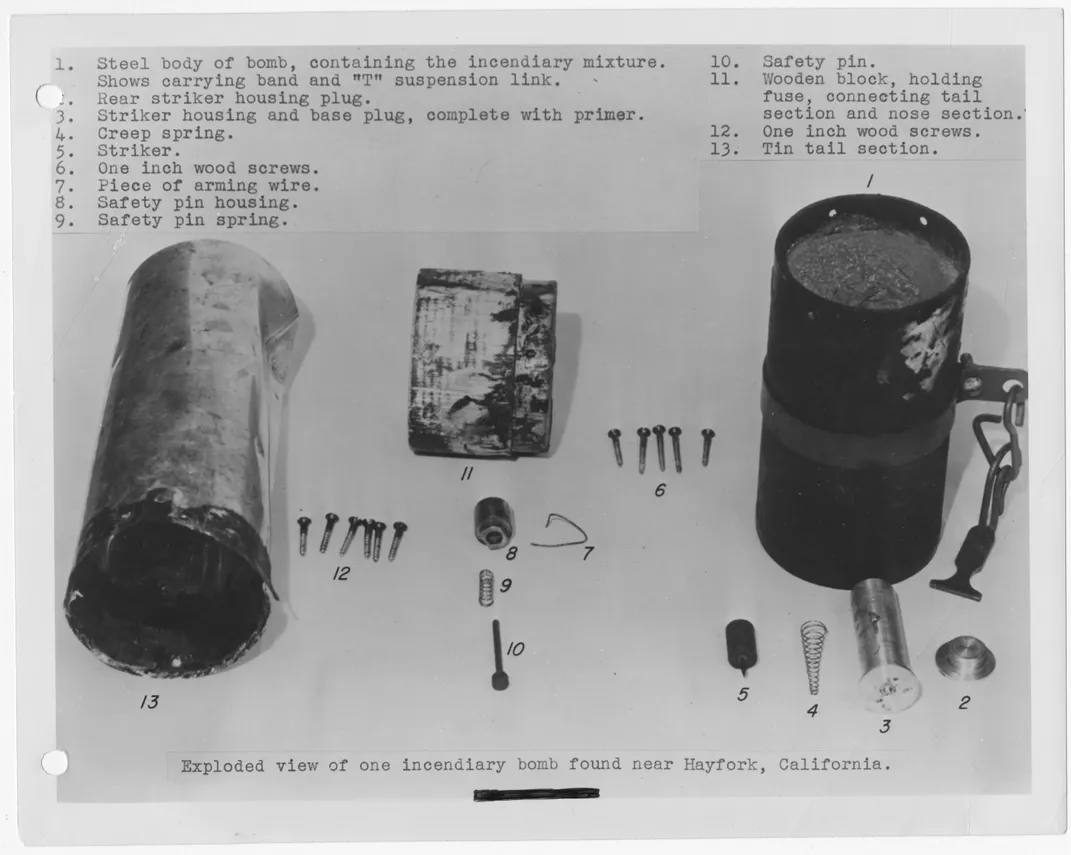

In the months leading up to that spring day on Gearhart Mountain, there had been some warning signs, apparitions scattered around the western United States that were largely unexplained—at least to the general public. Flashes of light, the sound of explosion, the discovery of mysterious fragments—all amounted to little concrete information to go on. First, the discovery of a large balloon miles off the California coast by the Navy on November 4, 1944. A month later, on December 6, 1944, witnesses reported an explosion and flame near Thermopolis, Wyoming. Reports of fallen balloons began to trickle in to local law enforcement with enough frequency that it was clear something unprecedented in the war had emerged that demanded explanation. Military officials began to piece together that a strange new weapon, with markings indicating it had been manufactured in Japan, had reached American shores. They did not yet know the extent or capability or scale of these balloon bombs.

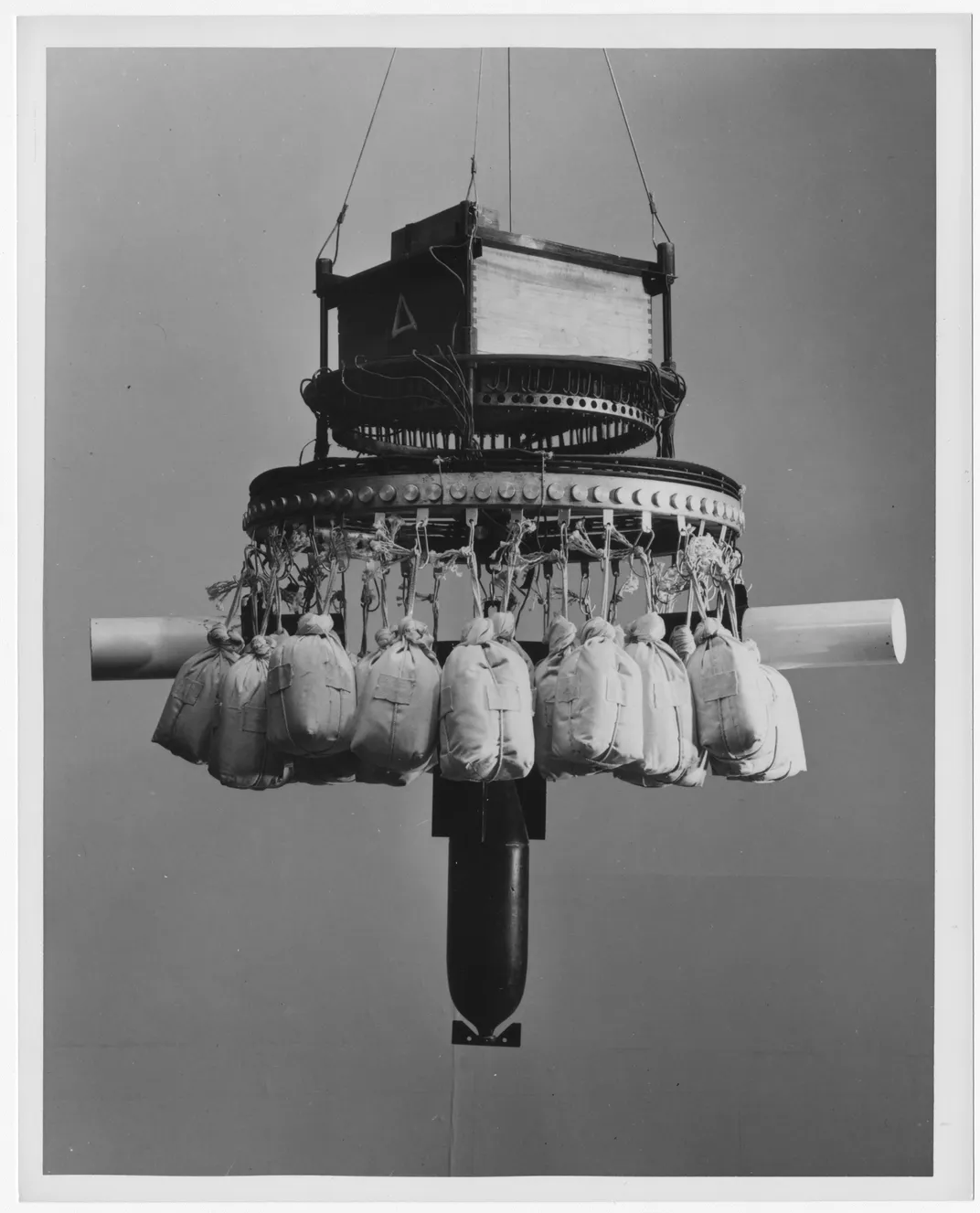

Though relatively simple as a concept, these balloons—which aviation expert Robert C. Mikesh describes in Japan’s World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America as the first successful intercontinental weapons, long before that concept was a mainstay in the Cold War vernacular—required more than two years of concerted effort and cutting-edge technology engineering to bring into reality. Japanese scientists carefully studied what would become commonly known as the jet stream, realizing these currents of wind could enable balloons to reach United States shores in just a couple of days. The balloons remained afloat through an elaborate mechanism that triggered a fuse when the balloon dropped in altitude, releasing a sandbag and lightening the weight enough for it to rise back up. This process would repeat until all that remained was the bomb itself. By then, the balloons would be expected to reach the mainland; an estimated 1,000 out of 9,000 launched made the journey. Between the fall of 1944 and summer of 1945, several hundred incidents connected to the balloons had been cataloged.

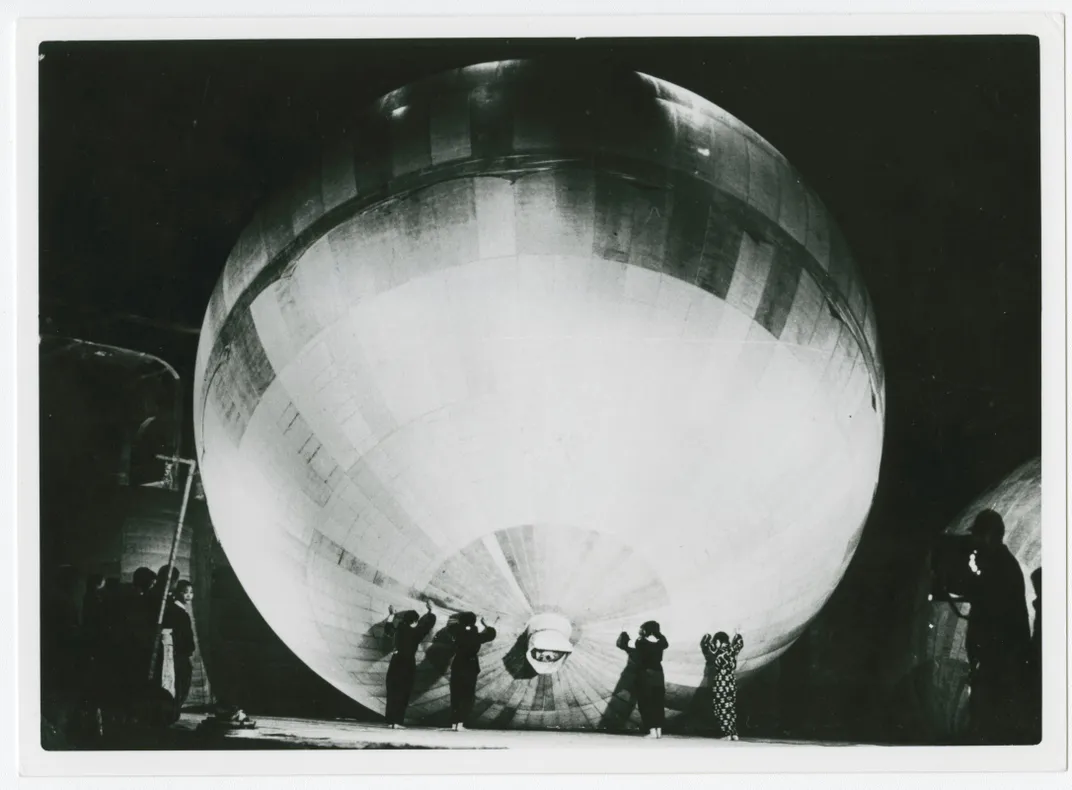

The balloons not only required engineering acumen, but a massive logistical effort. Schoolgirls were conscripted to labor in factories manufacturing the balloons, which were made of endless reams of paper and held together by a paste made of konnyaku, a potato-like vegetable. The girls worked long, exhausting shifts, their contributions to this wartime project shrouded in silence. The massive balloons would then be launched, timed carefully to optimize the wind currents of the jet stream and reach the United States. Engineers hoped that the weapons’ impact would be compounded by forest fires, inflicting terror through both the initial explosion and an ensuing conflagration. That goal was stymied in part by the fact that they arrived during the rainy season, but had this goal been realized, these balloons may have been much more than an overlooked episode in a vast war.

As reports of isolated sightings (and theories on how they got there, ranging from submarines to saboteurs) made their way into a handful of news reports over the Christmas holiday, government officials stepped in to censor stories about the bombs, worrying that fear itself might soon magnify the effect of these new weapons. The reverse principle also applied—while the American public was largely in the dark in the early months of 1945, so were those who were launching these deadly weapons. Japanese officers later told the Associated Press that “they finally decided the weapon was worthless and the whole experiment useless, because they had repeatedly listened to [radio broadcasts] and had heard no further mention of the balloons.” Ironically, the Japanese had ceased launching them shortly before the picnicking children had stumbled across one.

However successful censorship had been in discouraging further launches, this very censorship “made it difficult to warn the people of the bomb danger,” writes Mikesh. “The risk seemed justified as weeks went by and no casualties were reported.” After that luck ran out with the Gearheart Mountain deaths, officials were forced to rethink their approach. On May 22, the War Department issued a statement confirming the bombs’ origin and nature “so the public may be aware of the possible danger and to reassure the nation that the attacks are so scattered and aimless that they constitute no military threat.” The statement was measured to provide sufficient information to avoid further casualties, but without giving the enemy encouragement. But by then, Germany’s surrender dominated headlines. Word of the Bly, Oregon, deaths—and the strange mechanism that had killed them – was overshadowed by the dizzying pace of the finale in the European theater.

The silence meant that for decades, grieving families were sometimes met with skepticism or outright disbelief. The balloon bombs have been so overlooked that during the making of the documentary On Paper Wings, several of those who lost family members told filmmaker Ilana Sol of reactions to their unusual stories. “They would be telling someone about the loss of their sibling and that person just didn’t believe them,” Sol recalls.

While much of the American public may have forgotten, the families in Bly never would. The effects of that moment would reverberate throughout the Mitchell family, shifting the trajectory of their lives in unexpected ways. Two years later, Rev. Mitchell would go on to marry the Betty Patzke, the elder sibling out of ten children in Dick and Joan Patzke’s family (they lost another brother fighting in the war), and fulfill the dream he and Elsye once shared of going overseas as missionaries. (Rev. Mitchell was later kidnapped from a leprosarium while he and Betty were serving as missionaries in Vietnam; 57 years later his fate remains unknown).

“When you talk about something like that, as bad as it seems when that happened and everything, I look at my four children, they never would have been, and I’m so thankful for all four of my children and my ten grandchildren. They wouldn’t have been if that tragedy hadn’t happened,” Betty Mitchell told Sol in an interview.

The Bly incident also struck a chord decades later in Japan. In the late 1980s, University of Michigan professor Yuzuru “John” Takeshita, who as a child had been incarcerated as a Japanese-American in California during the war and was committed to healing efforts in the decades after, learned that the wife of a childhood friend had built the bombs as a young girl. He facilitated a correspondence between the former schoolgirls and the residents of Bly whose community had been turned upside down by one of the bombs they built. The women folded 1,000 paper cranes as a symbol of regret for the lives lost. On Paper Wings shows them meeting face-to-face in Bly decades later. Those gathered embodied a sentiment echoed by the Mitchell family. “It was a tragic thing that happened,” says Judy McGinnis-Sloan, Betty Mitchell’s niece. “But they have never been bitter over it.”

These loss of these six lives puts into relief the scale of loss in the enormity of a war that swallowed up entire cities. At the same time as Bly residents were absorbing the loss they had endured, over the spring and summer of 1945 more than 60 Japanese cities burned – including the infamous firebombing of Tokyo. On August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, followed three days later by another on Nagasaki. In total, an estimated 500,000 or more Japanese civilians would be killed. Sol recalls “working on these interviews and just thinking my God, this one death caused so much pain, what if it was everyone and everything? And that’s really what the Japanese people went through.”

In August of 1945, days after Japan announced its surrender, nearby Klamath Falls’ Herald and News published a retrospective, noting that “it was only by good luck that other tragedies were averted” but noted that balloon bombs still loomed in the vast West that likely remained undiscovered. “And so ends a sensational chapter of the war,” it noted. “But Klamathites were reminded that it still can have a tragic sequel.”

While the tragedy of that day in Bly has not been repeated, the sequel remains a real—if remote—possibility. In 2014, a couple of forestry workers in Canada came across one of the unexploded balloon bombs, which still posed enough of a danger that a military bomb disposal unit had to blow it up. Nearly three-quarters of a century later, these unknown remnants are a reminder that even the most overlooked scars of war are slow to fade.