1948 Democratic Convention

The South Secedes Again

The Democrats came to Philadelphia on July 12, seventeen days after the Republicans, meeting in the same city, had nominated a dream ticket of two hugely popular governors: Thomas E. Dewey of New York for president and Earl Warren of California for vice president.

The Democrats' man, President Harry S. Truman, had labored for more than three years in the enormous shadow of Franklin D. Roosevelt. In their hearts, all but the most optimistic delegates thought, as Clare Boothe Luce had told the Republican gathering, that the president was a "gone goose."

Truman, a failed haberdasher turned politician, had the appearance of a meek bookkeeper. In fact, he was feisty and prone to occasional angry outbursts. His upper-South twang did not resonate with much of the country. His many detractors wrote him off as a "little man" who had been unable to deal with difficult post-World War II issues—inflation and consumer shortages, civil rights for African-Americans and a developing cold war with the Soviet Union.

In the off-year elections of 1946, Republicans had gained firm control of both houses of Congress for the first time since 1928. Few Democrats believed Truman could lead them to victory in the presidential race. A large group of cold war liberals—many of them organized in the new Americans for Democratic Action (ADA)—joined with other Democratic leaders in an attempt to draft America's greatest living hero, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, as their candidate. The general seemed momentarily persuadable, then quickly backed away.

It was no coincidence that both parties met in Philadelphia. The city was at the center point of the Boston to Richmond coaxial cable, then the main carrier of live television in the United States. By 1948, as many as ten million people from Boston to Richmond could watch the tumultuous process by which the major parties selected their candidates. They could also see star journalists whom they had known only as voices, most notably the CBS team of Edward R. Murrow, Quincy Howe and Douglas Edwards.

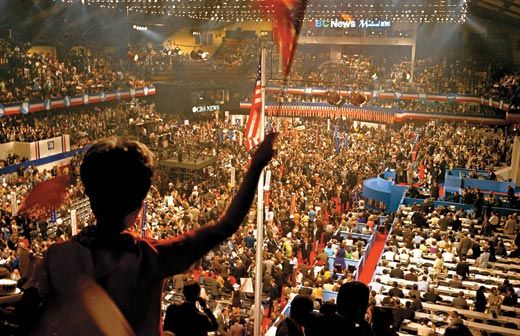

The parties met amid miles of media cable and wiring in Convention Hall, an imposing Art Deco arena decorated with exterior friezes that celebrated American values and the history of humankind. The structure could accommodate 12,000 people. Packed to the rafters on a steamy July day, heated by blazing television lights and possessing no effective cooling system, the great hall was like an enormous sauna.

The Democrats' keynote speaker was Senator Alben Barkley of Kentucky. A presence on Capitol Hill since 1912 and the Democratic leader in the upper house for more than a decade, Barkley was much liked throughout the party and a master orator in the grand tradition. His speech scourged the Republican-controlled Congress, quoted patron saints of the Democratic Party from Jefferson to FDR, expropriated Lincoln along the way and cited biblical text from the Book of Revelation. The delegates cheered themselves hoarse, and an ensuing demonstration waved "Barkley for Vice President" placards.

Truman, watching the proceedings on TV in Washington, was not amused. He considered "old man Barkley" (at age 70, six and a half years his senior) to be little more than a hail fellow with whom one sipped bourbon and swapped tall tales. The president wanted a young, dynamic and aggressively liberal running mate. He already had offered the slot to Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, who declined. With no backup, Truman turned to Barkley: "Why didn't you tell me you wanted to run, Alben? That's all you had to do." Barkley accepted.

By then, the attention of the delegates had shifted to a platform fight that marked the full emergence of the modern Democratic Party. African-Americans were an important Democratic constituency, but so were white Southerners. Previous party platforms had never gotten beyond bland generalizations about equal rights for all. Truman was prepared to accept another such document, but liberals, led by the ADA, wanted to commit the party to four specific points in the president's own civil rights program: abolition of state poll taxes in federal elections, an anti-lynching law, a permanent fair employment practices committee and desegregation of the armed forces.

Hubert Humphrey, mayor of Minneapolis and a candidate for Senate, delivered the liberal argument in an intensely emotional speech: "The time is now arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights." On July 14, the last day of the convention, the liberals won a close vote. The entire Mississippi delegation and half the Alabama contingent walked out of the convention. The rest of the South would back Senator Richard B. Russell of Georgia as a protest candidate against Truman for the presidential nomination.

Nearly two weeks after the convention, the president issued executive orders mandating equal opportunity in the armed forces and in the federal civil service. Outraged segregationists moved ahead with the formation of a States' Rights ("Dixiecrat") Party with Gov. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina as its presidential candidate. The States' Rights Party avoided outright race baiting, but everyone understood that it was motivated by more than abstract constitutional principles.

Truman was slated to deliver his acceptance speech at 10 p.m. on July 14 but arrived to find the gathering hopelessly behind schedule. As he waited, nominating speeches and roll calls droned on and on. Finally, at 2 a.m. he stepped up to the podium. Most of America was sound asleep.

He wore a white linen suit and dark tie, ideal for the stifling hall and the rudimentary capabilities of 1948 television. His speech sounded almost spit into the ether at the opposition. "Senator Barkley and I will win this election and make these Republicans like it—don't you forget that!" He announced he would call Congress back into session on July 26—Turnip Day to Missouri farmers—and dare it to pass all the liberal-sounding legislation endorsed in the Republican platform. "The battle lines of 1948 are the same as they were in 1932," he declared, "when the nation lay prostrate and helpless as a result of Republican misrule and inaction." New York Times radio and TV critic Jack Gould judged it perhaps the best performance of Truman's presidency: "He was relaxed and supremely confident, swaying on the balls of his feet with almost a methodical rhythm."

The delegates loved it. Truman's tireless campaigning that fall culminated in a feel-good victory of a little guy over an organization man. It especially seemed to revitalize the liberals, for whom the platform fight in Philadelphia became a legendary turning point. "We tied civil rights to the masthead of the Democratic Party forever," remarked ADA activist Joseph Rauh 40 years later.

In truth, the ramifications of that victory would require two decades to play out. In the meantime, Thurmond, winning four states and 39 electoral votes, had fired a telling shot across the Democrats' bow. Dixiecrat insurgents in Congress returned to their seats in 1949 with no penalty from their Democratic colleagues. Party leaders, North and South, understood the danger of a spreading revolt. Truman would not backtrack on his commitment to civil rights, but neither would Congress give him the civil rights legislation he requested.

His successors as party leader would show little disposition to push civil rights until the mass protests led by Martin Luther King Jr. forced the hands of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Only then would the ultimate threat of the Dixiecrats be realized—the movement of the white South into the Republican Party.

Alonzo L. Hamby, a professor of history at Ohio University, wrote Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman.