1968′s Computerized School of the Future

A forward-looking lesson plan predicted that “computers will soon play as significant and universal a role in schools as books do today”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201111161130121968-boys-life-magazine-cover-470x251.jpg)

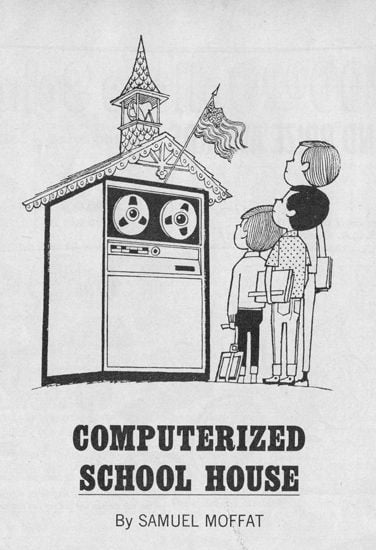

The September, 1968 issue of Boys’ Life magazine ran an article by Samuel Moffat about the computerized school of tomorrow. Boys’ Life is a monthly magazine started by the Boy Scouts of America in 1911 and is still published today. Titled “Computerized School House,” the piece explores things like how the computer terminal of the future would be operated (the “electronic typewriter” finally gets its due), how students of the future may be assessed in classrooms, and how computers in schools from all over the United States might be connected:

Picture yourself in front of a television screen that has an electronic typewriter built in below it. You put on a set of headphones, and school begins.

“Good morning, John,” a voice says. “Today you’re going to study the verbs ‘sit’ and ‘set.’ Fill in the blank in each sentence with the proper word — ‘sit,’ sat’ or ‘set.’ Are you ready to go?”

“YES,” you peck out on the typewriter, and class gets under way.

The machine clicks away in front of you. “WHO HAS ____ THE BABY IN THE MUD?” it writes.

You type “SAT.” The machine comes right back: “SET.” You know you’re wrong, and the score confirms it: “SCORE: 00.”

The article goes on like this for some time, listing other possible questions that a computer might ask a schoolboy of the future. The piece continues by describing just how far-reaching advancements in computer technology may be once the ball starts rolling:

A generation or so from now a truly modern school will have a room, or maybe several rooms, filled with equipment of the type shown on the cover of this issue. Even kindergarten children may be able to work some of the machines—machines such as automatically loading film and slide projectors, stereo tape recorders and record players, and electric typewriters or TV devices tied into a computer.

Customizable instruction seems to be the largest benefit touted by the article when it comes to every child having their own computer terminal:

The major advantage of the computer is that it helps solve the teacher’s biggest problem—individual instruction for every student. In a large class the teacher has to aim at the average level of knowledge and skill, but a computer can work with each child on the concepts and problems with which he needs the most help. A teacher can do this, too, but she often lacks the time required.

It goes on to say that kids can work at their own pace:

Computers combined with other teaching aids will provide schools with new flexibility in teaching. Students will be able to work at their own speeds in several subjects over a period of time. A boy might work all day on a science project, for instance, and complete his unit in that subject before some other children in his class had even begun. But they would be working on other subjects at their own speeds.

Connections not unlike the Internet were also envisioned in the article. Moffatt envisions a time when people from all around the United States would be connected through television and telephone wires. To put the timeline of networked computing into context, it would be another full year before the very first node-to-node message would be sent from UCLA to Stanford on October 29, 1969:

The electronic age also makes it possible to have the latest teaching materials immediately available even in outlying school districts. Television transmission and telephone cables bring pictures and computer programs from hundreds or thousands of miles away. Schools in Kentucky, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York, Pennsylvania and West Virginia, for example, are serviced by computers in California. The students are linked to their “teachers” by long-distance telephone lines.

The piece ends with some prognostication by unnamed publications and “computer specialists”:

Computers are expensive for teaching, and they will not become a major force in education for some time. But apparently they are here to stay. One educational publication predicted that “another generation may well bring many parents who cannot recall classwork without them.” And a computer specialist went even farther. He said, “… I predict that computers will soon play as significant and universal a role in schools as books do today.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)