The 1977 Conference on Women’s Rights That Split America in Two

Feminism and the conservative movement clashed over issues such as abortion and LGBTQ rights

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/0d/7a0de55e-639b-4d34-8aab-1e21f5e48a06/womensmarch1.jpg)

It was the early 1970s, and the women's movement was on a roll. The 92nd Congress, in session from 1971-72, passed more women’s rights bills than all previous legislative sessions combined, including the Title IX section of the Education Amendments (which prohibited sex discrimination in all aspects of education programs receiving federal support). The 1972 Supreme Court case Eisenstadt v. Baird gave unmarried women legal access to birth control, and in 1973, Roe v. Wade made abortion legal across the country. Even the avowedly anti-feminist President Nixon supported a 1972 Republican Party platform that included feminist goals, including federal childcare programs.

Grassroots feminism gained steam. Women across the country gathered to form rape crisis centers and shelters for victims of domestic abuse, produced the seminal book Our Bodies, Ourselves, and started businesses aimed at defeating sexism in the media.

And the capstone to the movement was supposed to be the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which aimed to give men and women equality in all aspects of life. It seemed likely to meet with speedy success after passing both the House and the Senate with overwhelming support in 1972. (It would need to be ratified by three quarters of state legislatures to become law.)

“Up to the mid-70s, both parties believed they ought to be supporting the women’s rights movement,” says Marjorie Spruill, who tackles the subject in her new book Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics.

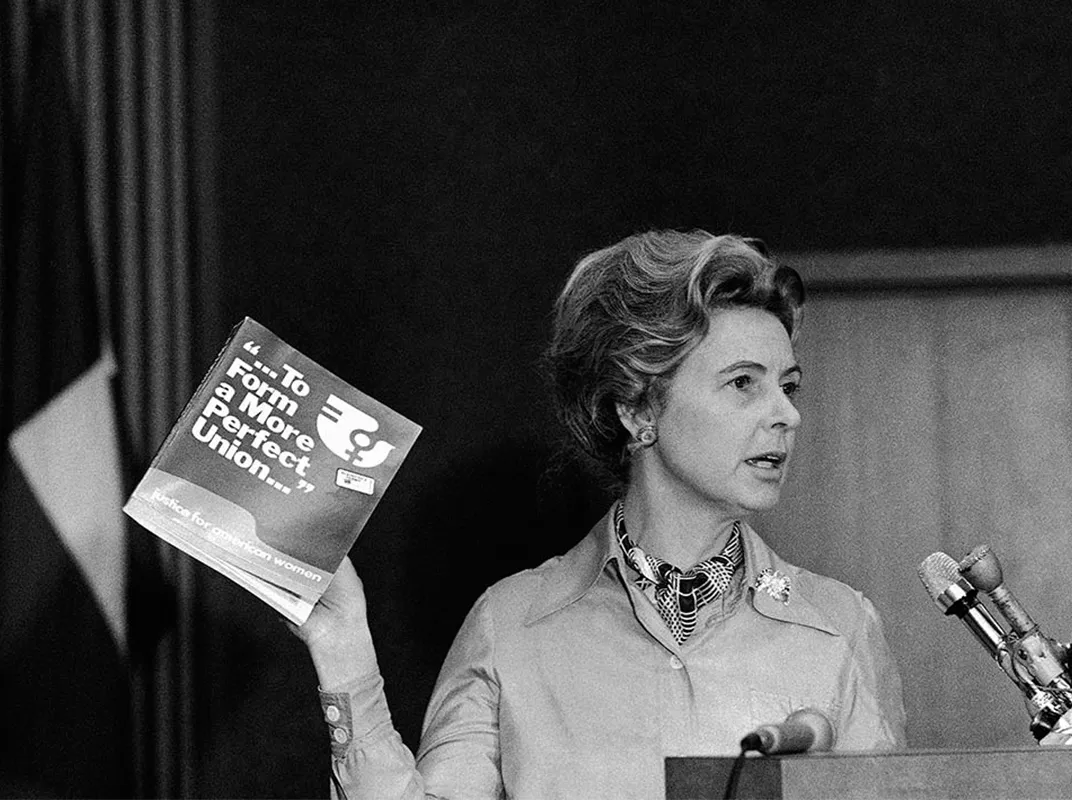

But that bipartisan support was short-lived. In 1972, conservative leader Phyllis Schlafly launched a movement whose goals—protecting women’s place as homemakers, fighting against abortion, and limiting government welfare and social support—have come to define the modern debate over women’s rights and the role of government in enforcing them. Schlafly campaigned hard (and successfully) to kill the ERA, and her vocal supporters succeeded in weakening the movement by making its issues partisan.

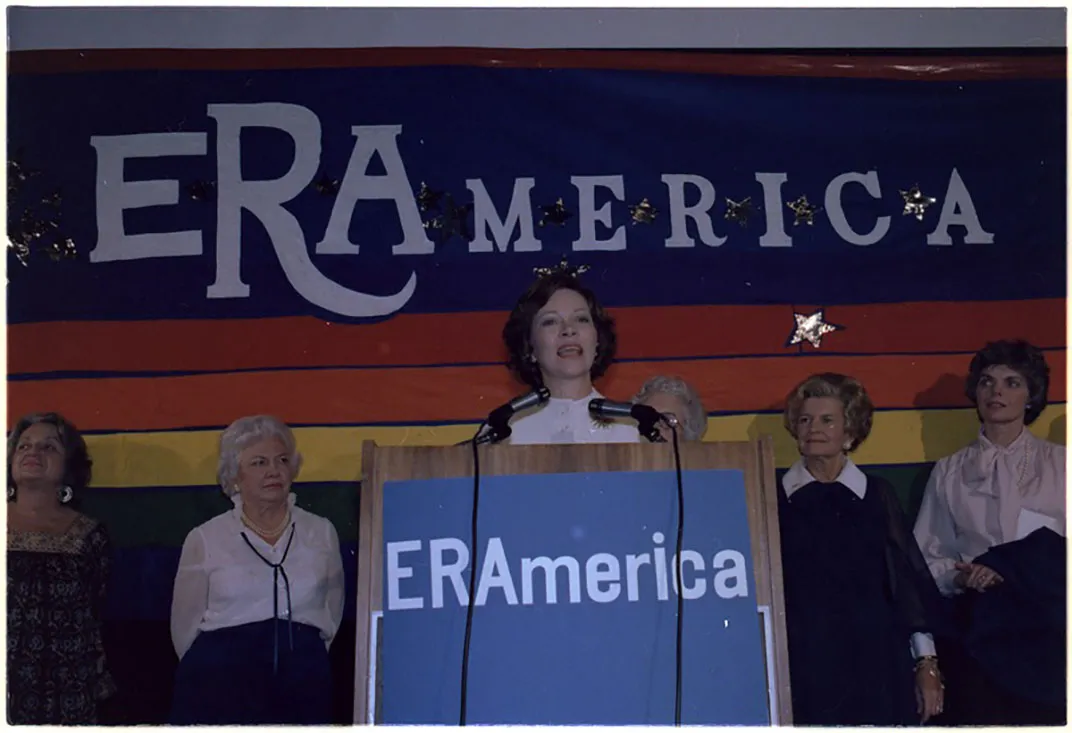

The differences between these two groups—feminists and conservatives—came to a head in 1977 in Houston. Inspired by a well-received, United Nations-sponsored event from two years prior, President Gerald Ford had established a national commission to investigate women’s issues, and Congress later voted to provide $5 million to fund the organization of regional conferences and a national gathering as the conclusion. The result of these efforts was the National Women’s Conference.

The conference was meant to unite all women and give them an opportunity to voice their hopes for the future of the government. Instead, the conference became a battleground, with Schlafly declaring it to be “Federal Financing of a Foolish Festival for Frustrated Feminists.” Schlafly led a counter-rally of 15,000 “pro-family” supporters, who proudly announced that they had paid their own way rather than relying on Congressional funding. The rally took place just five miles from the National Women’s Conference, and included pronouncements against abortion, lesbian rights and the Equal Rights Amendment. The sudden visibility of Schlafly’s counter-protest and her vocal followers led to a schism in political support for the women’s rights movement that has continued to this day.

“There was this major event in U.S. history in 1977 that totally went by me and apparently is something that people have not remembered very much despite the fact that it got massive media attention at the time,” Spruill says. “Gloria Steinem said, last year in her new book, that it is one of the most important things that ever happened that no one knows about. And I would really agree with that.”

To better understand the events that led us here, Smithsonian.com spoke with Spruill about her new book and the state of women’s rights in the world today.

It was a surprise to learn that both political parties supported women's rights early in the ‘70s. How did that fall apart?

During the administrations of Nixon and Ford, women’s rights advocates were pushing very strongly for anti-discrimination laws to knock down barriers to women’s advancement. Men and women in both parties felt that they needed to appear to be supportive, or at least not against it. The Equal Rights Amendment passed in Congress 1972 by absolutely overwhelming margins, only 8 votes cast against it in the Senate. Everyone [expected] it would be very quickly ratified. I remember being in college at that time, being passionately in favor and not understanding why anyone would be against it.

What happened is that conservative women had been watching the development of the women’s movement and talking about it, but hadn’t regarded it as a huge threat until the ERA came out. Then Phyllis Schlafly took a firm stand against it.

Immediately her followers in the states started to organize and demand that their states not ratify, or at least delay ratification until it could be studied. Basically that movement began and it grew and grew and pretty soon the rate of ratifications dropped and then ground to a halt by 1975; at that point they needed just four more states. They only got one more, Indiana in 1977.

The ERA bandwagon ground to a halt because conservative women had been able to create enough doubts about it that it made state legislators back off. Schlafly’s argument was that women would give up their right to be supported by their husbands, and she pressed really hard on the draft issue [since women would be required to register].

Any constitutional amendment is very hard by design to get through. Since you have to have three fourths of the states, the people supporting it have a much bigger challenge than those against it. Like the work of a defense lawyer, all they have to do is create reasonable doubt and that’s what happened with the Equal Rights Amendment.

This anti-ERA movement is largely a movement of Christian conservatives. Because they’re up against federal meddling and social engineering and efforts to bring about unwanted social change, it meant people who objected to federal activity also rallied. That included groups from the John Birch Society to the Ku Klux Klan.

Of all the issues the women’s movement tackled—race, social and economic inequality, sexism in the workplace, childcare—abortion and LBGTQ issues really seem to have been the most divisive. Why is that?

When you think about it, most of the other issues are things like equality of access to higher education, the opportunity to be paid equally for your work, the opportunity to be able to advance in your occupation, the opportunity to get equal credit—lots of these things are something that conservative women and feminists were more likely to agree on. On these two issues, they are both loaded with religious and moral significance. When you have things that people believe are moral issues, both sides are far less willing to compromise.

What was the idyllic past Phyllis Schlafly and the conservative women were trying to preserve?

I see it as a ringing endorsement of that ideal from the 1950s. It wraps together Schlafly’s Cold War American nationalism, her religious beliefs. [Schlafly felt that] God had favored the American nation. She compared it to the Soviet Union and Cuba, where women were equal in theory, but had to put their children in childcare. To her, the real heroes weren’t the feminists complaining about women’s roles, but Clarence Birdseye and Thomas Edison and others who had used technology to make things easier for the American housewife. The people who built refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, were the real heroes. Isn’t that remarkable?

What I see here is American society going through a massive technological, demographic, social and economic change after WWII, with the women’s rights movement on the one hand and conservative movement on the other hand. The women’s movement saw enormous opportunity and the thing that was in the way were laws and customs blocking women’s advance.

On the other hand, you see a group of women who are deeply invested in the traditional ideal of women’s role in family life. For many of them, their religious traditions and convictions supported the idea of the man being in charge and the wife being treasured by him and taking care of the family. To them, the feminist movement was urging women—and the government—to no longer support and protect that family structure. Rather than blaming social, demographic, scientific, technological changes, they saw women streaming into the workforce and blamed feminists.

Do you think this conservative pushback has been successful, other than keeping the ERA from being ratified?

The women’s movement has continued to press forward for opportunities and the conservative gains have been not very extensive, frankly. I would say there are two major ways the conservatives have succeeded since the ’80s. First has been on abortion. The pro-life movement has gained strength and there have been many barriers to women gaining safe and legal abortions and that is certainly in grave danger at the present moment. But the other main success that the conservatives had was in demonizing “feminism” as a term, as a movement, as a word. They succeeded in making a movement that was very diverse in ideology, in lifestyle, in every way—in making it seem radical and making the women in it appear to be selfish and man-hating and unattractive in every way.

This deep divide between two ideologies has continued until today. Do you think we’ll be able to overcome it?

At the moment, things are looking rather grim. The 2016 election showed this trend towards the polarization and growing partisanship in our nation. To see the two parties nominate people who were so completely opposite in their positions on issues related to women and gender and many other things, it’s really striking and dramatic. I’ve never seen it reach a point where it’s this bitterly divided. I do think that Trump’s election has brought more and more people who disagree with him into political activism. It woke up a lot of people who had grown complacent about the victories of the women’s movement, because under the eight years of the Obama administration he was so strongly a supporter of women’s rights.

I’m not feeling completely pessimistic because so many people have awakened. If they continue to pay attention, they will do everything possible to safeguard the progress that has been made, and basic American civil liberties, and the Constitution. Having an awakened citizenry is a good thing, but the fact that people come down on such opposite sides are not talking to one another, and hardly anybody who’s a Trump supporter knows somebody who’s a Hillary supporter, and they get their information from different sources and don’t trust the media—that is deeply disturbing and makes me worry how we’re going to get past this. It makes me think we’ll continue to have heated battles in the coming years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)