The Slaves of the White House Finally Get to Have Their Stories Told

Long ignored by historians, the enslaved people of the White House are coming into focus through a new book by Jesse J. Holland

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/33/1833540e-104b-45ca-9dd7-d2a0f35f544e/be075253.jpg)

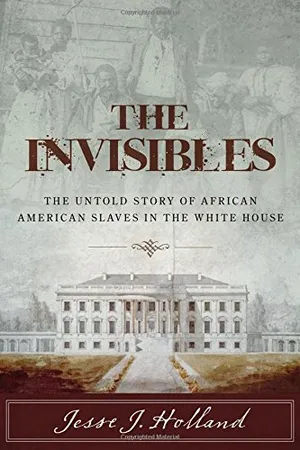

President Barack Obama might be the first black president to serve in the White House, but he certainly was not the first black person to live there. Yet the history of the original black residents of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue has been sparsely reported on, as Associated Press reporter Jesse J. Holland discovered when he began researching his latest book, The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House. The Invisibles—a smart sketch on the lives of these men and women in bondage—is intended to serve as a historical first take. Holland’s goal writing about the slaves who resided alongside 10 of the first 12 presidents who lived in the White House is to start a conversation on who these enslaved people were, what they were like, and what happened to them if they were able to escape from bondage.

Your first book, Black Me Built the Capitol: Discovering African-American History In and Around Washington, D.C., touches on similar themes to The Invisibles. How did you get the idea for writing about this specific lost chapter of black history in the United States?

I was covering politics for the AP back when Obama was doing his first presidential campaign around the country. He decided that weekend to go back home to Chicago. I was on the press bus, sitting in Chicago outside of Obama’s townhouse, trying to think about what book to write next. I wanted to do a follow-up book to my first—which was published in 2007—but I was struggling to come up with a coherent idea. As I was sitting there in Chicago, covering Obama, it hit me: We had always talked about the history of Obama possibly becoming the first black president of the United States, but I knew Obama couldn’t have been the first black man to live in the White House. Washington, D.C. is a southern city and almost all mansions in the South were constructed and run by African Americans. So I said to myself, I want to know who these African American slaves were who lived in the White House.

How did you begin researching the story?

Only one or two of the slaves who worked for the president ever had anything written—Paul Jennings wrote a memoir—but there’s very little written about these men and women enslaved by the presidents. Most of my research was done by reading between lines of presidential memoirs and piecing all of it into one coherent narrative. Presidential historians that work at Monticello and Hermitage in Tennessee, for example, want this research done; they were thrilled when someone wanted to look at these records and were able to send me a lot of materials.

What were some of the more unexpected details you can across during your research?

One of the things that surprised me is how much information was written about these slaves without calling them slaves. They were called servants, they were staff— but they were slaves. Andrew Jackson’s horse racing operation included slave jockeys. There have been things written about Andrew Jackson and horses and jockeys, but not one mentioned the word “slaves.” They were called employees in all the records. So, it’s there, once you know the words to look for. I was also surprised with how much time the presidents spent talking about their slaves in those same code words. When you start reading memoirs, ledgers, these people show up again and again and again, but they are never actually called slaves.

Which president’s relationship with his slaves surprised you the most?

With Thomas Jefferson, there’s been so much said about him and his family, I don’t know if I discovered anything new, but everything is about context. We mostly talk about Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, but James Hemings would have been the first White House chef, if not for the spat between him and Thomas Jefferson.

Or you look at [Joseph] Fossett being caught on White House grounds trying to see his wife. It surprised me because you would think things like that would be more well known. The Thomas Jefferson story is overwhelmed about him and Sally Hemmings, but there are so many stories there.

Definitely.

Also, with everything we know about George Washington, I was shocked to find he advertised in the newspaper for a recapture of an escaped slave. I hadn’t thought any had escaped until I started working on this and then to find he’d advertised for the return, that’s not subtle. He wanted him back and he took whatever route he could take, including taking out an advertisement.

How does reading about these slaves help us better understand the early presidents?

In the past, we’ve talked about their attitudes in general toward slaves and now we can talk in specifics, and include the names of the slaves they were dealing with. That’s one thing I hope not just historians, but people in general pick out of the abstract. Begin talking about the specifics: this is how the relationships between George Washington and William Lee or Thomas Jefferson with James Hemings or Andrew Jackson with Monkey Simon. This helps us understand presidents’ policies when it came to slavery and race relations at this time. If they said something publicly but did something else privately, it gives us insight into who they are.

Was it frustrating writing around the limited information available?

One of the things I talk about in the book is that this is just a first step. There is no telling how many stories that have been lost because, as a country, we didn’t value these stories. We’re always learning more about the presidents as we go forward and we’ll also learn more about the people who cooked their meals and dressed them.

There’s people doing great work on slave dwellings in the South, great work on history of African American cooking, slave cooking in the past. It’s not the information wasn’t always here, we’re just interested in it now. As we go forward and learn more information and find these old hidden ledgers and photographs, we’ll have a clearer picture of where we came from as a country and that will help us decide where we are going in future.