First Wolverine Family Makes a Home in Mount Rainier National Park in 100 Years

A trio of wolverines—a mom and two kits—were spotted on camera traps in the park

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/0a/670a8498-388c-4f4e-90b4-f39833282baa/2020_aug25_wolverines.jpg)

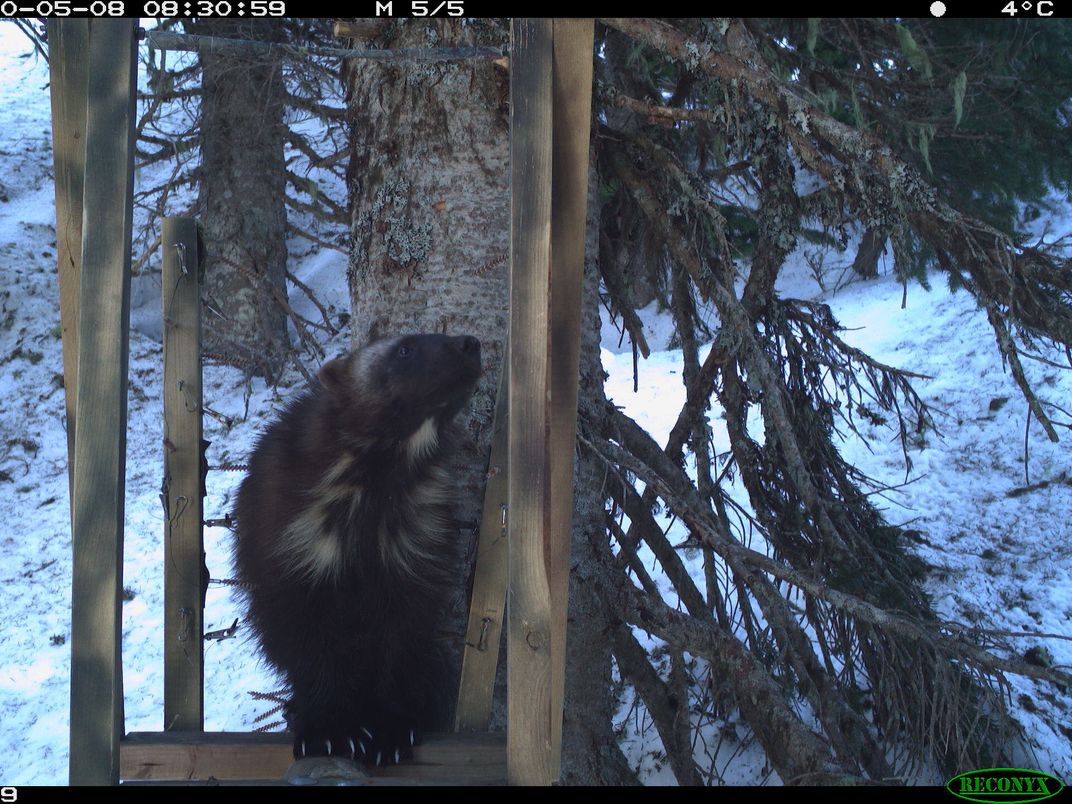

A mama wolverine and her two kits have made a home in Mount Rainier National Park in Washington State, the park announced last week. The trio were spotted on wildlife cameras set up by the Cascades Carnivore Project, Kelsie Smith reports for CNN.

Although wolverines are common in Canada and Alaska, unregulated trapping in the 19th and early 20th centuries severely reduced their population further south, Michele Debczak writes for Mental Floss. Now, scientists estimate that between 300 and 1,000 of them remain in the contiguous United States.

The animals are the largest members of the weasel family, and look like miniature bears with long tails and a fluffy ruff. But they’re elusive. Mount Rainier National Park staff suspected wolverines had moved into the park in 2018. They set up cameras to study the local wolverines, which the park’s wildlife experts could identify by their unique white markings.

This summer, they spotted the nursing mother, who was named Joni by the Cascades Carnivore Project. That’s a good sign for the species and for the park.

"It's really, really exciting," Mount Rainier National Park superintendent Chip Jenkins says in a statement. "It tells us something about the condition of the park—that when we have such large-ranging carnivores present on the landscape that we're doing a good job of managing our wilderness."

Wolverines are solitary critters that need a lot of space to themselves. In 600 square miles of high-quality habitat, there might be about six wolverines on average, Anna Patrick reports for the Seattle Times. They’re carnivorous and normally hunt small mammals like rabbits and rodents. But if a larger animal like a caribou is sick or injured, a wolverine might attack it, according to National Geographic.

They also eat carrion, especially in winter when prey is scarce. The small predator is well adapted to the cold, as its thick, brown coat made it a prime target of trappers in North America. And mother wolverines, like Mount Rainier’s Joni, use snowpack to build their dens.

The park points out that wolverines are losing territory because climate change is reducing the snowpack in their southern range. A family of wolverines hasn’t been seen in Mount Rainier National Park for about 100 years.

“Many species that live at high elevation in the Pacific Northwest, such as the wolverine, are of particular conservation concern due to their unique evolutionary histories and their sensitivity to climate change,” says Jocelyn Akins, founder of the Cascades Carnivore Project, in the statement. “They serve as indicators of future changes that will eventually affect more tolerant species and, as such, make good models for conservation in a changing world.”

Although so few wolverines remain in the U.S., they aren’t currently protected under the Endangered Species Act. Some groups, including the Biodiversity Legal Foundation, began petitioning for the wolverine’s protection 20 years ago, Laura Lundquist reports for the Missoula Current. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has until the end of August to make a decision on the matter.

At the same time, wolverines have been spotted outside of their normal range, including along the Long Beach Peninsula and walking down a road in the rural community of Naselle, Washington, per CNN.

But for the most part, wolverines will avoid people or run away if they encounter a human.

“Backcountry enthusiasts, skiers, snowshoers and snowmobilers can help us monitor wolverines and contribute to studying their natural return to the Cascade ecosystem,” park ecologist Tara Chestnut says in the statement.

The Mount Rainier National Park, working with the National Park Fund, created a downloadable carnivore tracking guide to help hikers recognize tracks they encounter in the backcountry.

“Wolverines are solitary animals and despite their reputation for aggressiveness in popular media, they pose no risk to park visitors,” Chestnut adds. “If you are lucky enough to see one in the wild, it will likely flee as soon as it notices you.”