A Capitol Vision From a Self-Taught Architect

In 1792, William Thornton designed America’s defining monument, where a new visitor center opens in December

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/capitolfellow_dec08_631.jpg)

In the torrid summer of 1792, William Thornton, the 33-year-old son of wealthy planters on the Caribbean island of Tortola, labored over a set of architectural drawings. Thornton, who had been trained as a physician but was now trying his hand at architecture, seemed unaware of the oppressive heat. As his sheaf of sketches grew, Thornton's thoughts were focused on the nation that had inspired his endeavor—the fledgling democracy of the United States, whose shores lay more than a thousand miles distant. When he looked up from his desk, Thornton gazed out across the plantations of Pleasant Valley, where slaves toiled in the terraced fields. Since the 1750s, Thornton's Quaker family had prospered on 12-mile-long Tortola (today part of the British Virgin Islands), where sugar, cotton, tobacco and indigo were grown. By the 1790s, export crops carpeted the island's deep valleys and razorback ridges, bringing great fortunes to many and guilt to a few, including Thornton, who abhorred slavery.

As Thornton refined his drawings, the air was thick with the pungent scent of sugar cane being refined into molasses and rum; the cooing of mountain doves mingled with the thud of waves onshore in nearby Sea Cow Bay. Gradually, a magnificent building—the United States Capitol—took shape on Thornton's papers. The structure, he believed, would rise as a shrine to republican government. (On December 2, 2008, the most recent addition to the nation's defining monument—the $621 million Capitol Visitor Center—will be inaugurated when it opens to the public after six years of construction.)

"I have made my drawings with the greatest accuracy, and the most minute attention," Thornton wrote to federal commissioners charged with selecting a design from more than a dozen submissions. "In an affair of so much consequence to the dignity of the United States," he added, it was his hope that "you will not be hasty in deciding."

Several months earlier, in the spring of 1792, the government of President George Washington had begun soliciting designs for the Capitol. The intention was to create a structure that would embody the lofty ideals of the new nation and serve as a defining landmark in a new federal city that was to rise on the banks of the Potomac River. According to historian Kenneth R. Bowling of George Washington University, our first president well understood the significance of the national capital's location. By siting the city "in the Middle States," says Bowling, President Washington envisioned that future city would play "a fundamental role in the survival of the Union, by uniting the North, South and West." The Capitol building, Bowling adds, would serve as the city's political anchor—a physical counterpart to the Constitution and a kind of temple to the secular religion of republican government.

Heated competition for the site of the capital city had raged for years, reaching its height during the First Federal Congress, which met in New York from 1789 to 1790. Fierce backroom negotiations went on for months. In the end, factions advocating for Philadelphia and New York were outmaneuvered by those who argued for a location on the Potomac River, equidistant between North and South, easily defended and naturally attractive to international trade. Southerners also feared that establishing a capital in the North—where those in bondage were already being emancipated—would help to undermine slavery. (As a conciliatory gesture to Pennsylvania, Philadelphia was named the temporary capital until Congress could take up residence on the Potomac in 1800.)

By mid-1792, the "city" existed as little more than a speculative if magnificent plan, mapped out by French-born engineer Pierre Charles L'Enfant. (Washington had first met L'Enfant at Valley Forge during the terrible winter of 1777-78, when L'Enfant served under the commander in chief.) Only a handful of streets had been laid out, designated by surveyor's stakes and lines of felled trees radiating across landowners' forests and pastures. Washington and his allies wanted buildings that would embody the nation's hoped-for future. "In our Idea the Capitol ought in point of prosperity to be on a grand Scale, and that a Republic especially ought not to be sparing of expenses on an Edifice for such purposes," wrote the three recently appointed commissioners overseeing creation of the new capital city.

The commissioners also solicited designs for an official residence to be known as the President's House. The winners would receive $500 and, in the case of the Capitol, a city lot as well. For the President's House, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, the administration's resident aesthete, had expressed a desire for something "modern," perhaps, he suggested, resembling the Louvre or another Parisian landmark. For the Capitol, however, Jefferson had in mind the architecture of classical Rome: "I should prefer the adoption of some of the models of antiquity, which have had the approbation of thousands of years."

Indeed, it was Jefferson who had come up with the name Capitol Hill, consciously invoking the famous temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill in ancient Rome. (The tract of land slated for the Capitol had been known as Jenkins Hill.) Jefferson was also appropriating the mantle of the Roman Republic, with its political freedoms and popular government. "Jefferson didn't want to take any chances with the Capitol and the public buildings," says William C. Allen, architectural historian in the Office of the Architect at the U.S. Capitol. "He wanted them based on buildings that were already famous and admired. Basically, he wanted the Europeans to stop laughing at us."

The contest for the President's House was quickly decided and resulted in the appointment of James Hoban, an Irish-born architect from Charleston, South Carolina. The competition for the Capitol, however, presented a host of problems. Submissions began to arrive in July 1792. One design featured the statue of a gigantic bird, reminiscent of a turkey, perched atop a cupola. Another plan evoked a county courthouse; a third resembled an army barracks. Jefferson himself drew a plan, which he never submitted, that he based on the circular, second-century a.d. Pantheon, the most renowned surviving temple in Rome; he incorporated oval chambers under the dome, intended to house the three branches of government. Washington did not hide his disappointment in the submissions. "If none more elegant than these should appear...the exhibition of architecture will be a very dull one indeed," he said.

Washington and Jefferson reluctantly focused on the only plan from a professional architect, French-born Étienne (Stephen) Sulpice Hallet, whose ornate and monumental scheme, calling for multiple exterior and interior sculptures, became known as the "fancy piece." Hallet had been at work for months, refining his design, when, in January, a late entry appeared. The deadline had come—and gone—six months before, but Thornton had nonetheless requested, and received, permission to submit his plan.

William Thornton was not a man to be easily dismissed. The affable Thornton—"full of hope, and of a cheerful temper," as his wife, Anna Maria, described him—was a nonconformist by temperament, a man who favored lace-trimmed garments that belied his austere Quaker origins. He was already one of the most celebrated figures of his time, a polymath and inventor. An acquaintance, jurist William Cranch, who would become chief justice of the D.C. federal court, said Thornton was "a little genius at everything." Born on Tortola in 1759, he was sent at age 5 to be educated in England. After completing medical studies at Scotland's University of Edinburgh in his 20s, Thornton began corresponding with the astronomer William Herschel. The young medical student's connections also resulted in an introduction, in Paris, to Benjamin Franklin, the American ambassador to France. Thornton's range of interests encompassed natural history, botany, mechanics, linguistics, architecture, government and—in another departure from the sober Quakers—horse racing. He had already helped to finance development of a steamboat and to design its boiler; invented a steam-operated gun; and proposed a "speaking organ to be worked by water or steam and to preach to the whole city." He was the author of a treatise on comets. He also advocated ending bondage by resettling emancipated slaves in Africa, where Thornton envisioned a colony characterized by "the support of places of worship, of schools, and societies for the encouragement of science" and a legal system based on the Anglo-American model. (His ideas would ultimately influence the founding of Liberia.)

In 1786, Thornton embarked for the United States, where, he believed, "virtue and talents were alone sufficient to elevate to office, instead of hereditary rights derived from men whose meanness or vices were the principal causes of their grandeur." The young physician, who would become a citizen in 1788, eventually settled in Philadelphia, where he set up a practice. Soon, he would count James Madison among his friends. (He and Madison lived in the same Philadelphia lodging house during the Constitutional Convention.)

Even far from home, Thornton was preoccupied with liberating his family's slaves. "I am induced to render free all that I am possessed of, by the dictates of conscience, and the uncommon desire I have to see them a happy people," he wrote to a friend in England. "My inclination is however in some degree counter to the prejudices of my parents—prejudices absorbed by a West Indian education, and which, by the continued habit of slavery, are now become shackles to the mind." In 1790, he departed Philadelphia for Tortola. During two frustrating years on the island, Thornton met with intractable opposition from his mother and stepfather, and from local authorities, who regarded him as a dangerous revolutionary whose actions, they feared, would lead to slave rebellion and economic ruin.

It was during this time on Tortola that Thornton learned of the Capitol design competition; he immersed himself in the project with a zeal bordering on passion. "First I thought of the amazing extent of our country, and of the apartments that the representatives of a very numerous people would one day require," he would later recount the genesis of his design to a British friend, Anthony Fothergill. "Secondly I consulted the dignity of appearance, and made minutiae give way to a grand outline, full of broad prominent lights and broad deep shadows." Then, he added, "I sought for all the variety of architecture that could be embraced in the forms I had lain down." Finally, he wrote, "I attended to the minute parts; that we might not be deemed deficient in those touches which a painter would require in the finishing."

Thornton had no formal training in architecture; he took his inspiration largely from examples in books. The design that he drafted was essentially a huge Georgian mansion, its entrance a six-columned portico. In November 1792, Thornton hand-carried that original plan to Philadelphia, still the seat of government. There, he learned of the earlier uninspired entries, the commissioners' request for new drawings from Hallet and of Jefferson's particular admiration for the Pantheon. He also discovered that President Washington had decided that the proposed capitol should incorporate a presidential apartment, as well as a dome—that feature, it was believed, would impart a special grandeur, rendering the structure unique in North America.

In January 1793, Thornton produced a second plan, one which represented a quantum leap in scale and originality. The building would, by American standards, be huge: 352 feet in length, three and a half times longer than Independence Hall in Philadelphia and far more elaborate than anything attempted in the Western Hemisphere. Symmetrically proportioned wings to the north and south provided quarters for the Senate and House of Representatives. The building's focal point was a majestically domed rotunda fronted by a Corinthian portico, its 12 columns set on a one-story gallery. Inside the rotunda, Thornton envisioned a marble equestrian statue of George Washington, "who by his military achievements and noble exertions hath so eminently aided his country in obtaining freedom, who by his services as a statesman, hath...so dignified his station by his exemplary virtuous life."

"Thornton's design," writes William Allen, "was partly an essay in the emerging neoclassical style and partly an orthodox, high-style Georgian building." The dome and portico, he adds, "were both reminiscent of...the Pantheon. Thornton's adaptation of the Pantheon linked the new republic to the classical world and to its ideas of civic virtue and self-government." (Today, photocopies of Thornton's hand-drawn plans are displayed in the Capitol.)

Thornton's design was fully realized: he even imagined a series of statues incorporating a uniquely American iconography. Images including buffalo, elk and Indians would accompany figures from the ancient world, Hercules and Atlas: thus, emblems of the new nation's wilderness and westward expansion would be wedded to classical symbolism. Thornton's design overwhelmed George Washington with its "grandeur, simplicity, and beauty."

By early February, Jefferson made it clear to federal commissioners that Thornton's design enjoyed official favor, noting that it "so captivated the eyes and judgment of all as to leave no doubt you will prefer it." On April 5, the commissioners informed Thornton that "the President has given his formal approbation of your plan." Thornton's reaction to the news is unrecorded. However, he quickly got down to work. Five days later, he submitted a minutely detailed report, outlining plans for everything from placement of windows and water closets to committee rooms and vestibules. He proposed, too, a statue of Atlas holding up Earth, which, Thornton noted, "has an allusion to the members assembled in this house bearing the whole weight of government." (The sculpture would never be commissioned.)

Thornton "succeeded, where others with practical experience had failed, because he grasped and was able to delineate the fundamental idea of the building," writes C. M. Harris, an independent historian who is the editor of Thornton's papers. "His knowledge of the ancient Roman writers allowed him to perceive the form and purpose, the political implications in Jefferson's neoclassical concept of a modern capitol....[His plan] translated the Constitution into architectural form, creating a unique American building type." Thornton, adds Harris, "redefined the sacred element of the temple, enshrining the lawmaking process upon which the success of the new republic depended, rather than any god or the authority of the state."

The design, however brilliant, was not perfect. Although the Capitol's exterior was magnificent, Thornton lacked a crucial skill: the architect's ability to picture an interior in three dimensions. Thus, when professional builders examined his plans later in 1793, it became clear that its columns were spaced too widely to support architraves and that the staircases lacked sufficient headroom. The conference room's interior colonnade, Jefferson objected, had "an ill effect to the eye, and will obstruct the view of the members: and if taken away, the ceiling is too wide to support itself." Key sections of the building lacked sufficient light and air. The president's office had no ventilation at all, while the Senate chamber was allotted only three windows. "Had Thornton's plan been followed, the Senate would have suffocated," says Allen.

The task of remedying the problems was assigned to none other than, as the commissioners put it, "poor Hallet," whose own design had just been rejected. Hallet's feelings, Washington wrote with some embarrassment, would have to be "sa[l]ved and soothed to prepare him for the prospect that the dr's plan will be preferred to his." Although Hallet did as he was bidden, he continued to lobby, unsuccessfully, for his own design to replace Thornton's.

On September 18, 1793, a scene of nearly medieval pageantry unfolded in the new federal city as the moment came to lay the Capitol's cornerstone. President Washington was accompanied by his brotherhood from local Masonic lodges. (The group's origins lay in the workmen's guilds of the Middle Ages, which by the 18th century had evolved into an elite fraternity that promoted the Enlightenment ideals of rationality and fellowship. During the Revolutionary War, Freemasonry had served as a powerful bonding force among officers of the Continental Army.) Washington and his compatriots marched resplendent in regalia of satin aprons, badges and sashes, accompanied by a military band and soldiers of the Alexandria Volunteer Artillery. One dignitary carried the Bible on a satin cushion, another a ceremonial sword. A local newspaper, the Columbia Mirror and Alexandria Gazette, reported "music playing, drums beating, colors flying, and spectators rejoicing." Surveyors and federal officials, stonecutters and carpenters, along with prominent citizens, picked their way around potholes and tree stumps to Capitol Hill, along the route of what one day would be Pennsylvania Avenue. There, artillerymen unlimbered their guns and fired a cannonade that echoed resoundingly. Washington clambered into a trench where he laid the cornerstone. After another 15-round cannonade, "The whole company," reported the Mirror and Gazette, feasted on "an ox of 500 pounds' weight."

The Capitol had been scheduled for completion by 1800. However, progress was hampered by incompetent management, contentious debates over the federal city's future, labor disputes and shoddy construction. In 1795, as a result of slipshod work, the building's foundation collapsed; not long afterward, a foreman absconded with $2,000 in workers' salaries. Funding presented even bigger obstacles. The federal government initially had refused to appropriate public revenues for development of the capital city, insisting that money be raised through sales of municipal land, a system that failed repeatedly. Finally, in 1802, Congress grudgingly agreed to pay the project's debt from the Treasury.

Despite the setbacks, the Capitol's North Wing, housing the Senate's semielliptical chamber, was completed, if only barely, in time for the arrival of Congress from Philadelphia in 1800. (For the time being, the House of Representatives would meet in the second-floor library.) When members of Congress entered the building that November to hear President John Adams proclaim the official installation of the government in Washington, D.C., the scent of newly cut lumber and fresh paint hung in the air.

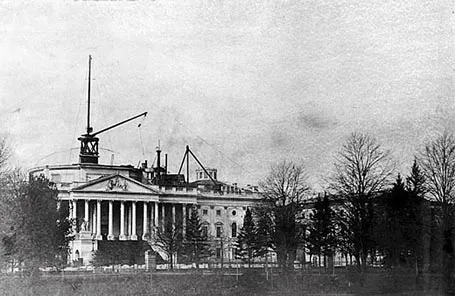

It would take 33 years to complete the building that Thornton had begun to envision on Tortola. As the structure was altered and enlarged over time, Thornton's name and his memory would be submerged beneath the work of others. The Capitol's South Wing was completed by architect Benjamin Latrobe in 1811. The rotunda and portico were at last finished in 1826, under architect Charles Bulfinch. Major expansions, including new House and Senate wings, altered the Capitol in the 1850s and 1860s (when Bulfinch's teacup-shaped dome also was replaced by the towering cast-iron dome punctuating the city's skyline today.)

However, elements of Thornton's design remain, including the original western facade of the wings, the stately Law Library Door at the southeast corner of the old North Wing and much of the eastern facade, now part of a corridor behind the East Front extension, erected between 1958 and 1961. The visitor center, plagued by delays and cost overruns, surveys the Capitol's history, incorporating interactive exhibits and a live feed from House and Senate chambers when Congress is in session.

Thornton's Capitol was the greatest design achievement of the early republic. "Thornton's stroke of genius was to put wings on the Pantheon, and to make them the working parts of the building, and the Pantheon a ceremonial part," says Allen. "He established for all time what the Capitol was to be. Everything that came later had to follow Thornton's design." His creation, Allen notes, would also inspire nearly every state capitol erected throughout the 19th century, most notably in North Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi. "By separating the wings, he also physically expressed the bicameral form of the government," Allen adds. "He got everything right at once: the size, the degree of grandeur, the Anglo-American feel. It was the perfect recipe. Some of the alternative submissions had too much salt, so to speak, others too much pepper. Others were overbaked. Thornton's was just right. It was a flash of genius."

Thornton lived the rest of his life in his adopted city, which, with characteristic effusiveness, he compared to Constantinople, boasting, "We are approaching a state which will, I doubt not, be the envy of the world." In 1794, President Washington appointed him to the three-man board of commissioners that oversaw the continuing development of the federal city. After the board was abolished in 1802, President Jefferson named him the head of the U.S. Patent Office, a position he held until his death, at age 68, in 1828. Thornton also designed several additional buildings that stand in Washington, including Octagon House (1798-1800), a couple of blocks from the White House and now a museum operated by the American Architectural Foundation, and Tudor Place (1816), a Georgetown mansion originally the home of the Peter family and now a museum as well.

Although Thornton's commitment to the emancipation of slaves diminished in the capital's proslavery climate, his enthusiasm for republican government never waned. He became an outspoken advocate of Greek independence and of democratic revolution in South America. To the end of his days, Thornton was consumed by a passionate desire to leave his mark on the world. He sensed, and feared, the ephemeral nature of fame. "I cannot rest when I think what I might have done, and reflect on what only I have done," he wrote to his cousin John Coakley Lettsom in January 1795. "I sicken at the idea, and lament the loss of time—God grant grace to me, and direct me to be, if possible, a benefactor to man....I must do more than I have ever yet done, or my name too will die."

Writer Fergus M. Bordewich's most recent book is Washington: The Making of the American Capital.