A Green Addition to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Meeting House

Architects of the First Unitarian Society’s new eco-friendly addition find inspiration in the ideas of original architect Frank Lloyd Wright

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/rendition-old-and-new-Meeting-House-631.jpg)

Back in 1946, members of the First Unitarian Society of Madison, Wisconsin, selected a visionary architect to design a new meeting space for their congregation. Did they also choose someone who was an early practitioner of “green” architecture?

At a meeting of the First Unitarian Society, Frank Lloyd Wright, one of its members (though not a regular attendee), was selected to design the growing congregation’s new Meeting House. His impressive portfolio at the time—Prairie School and Usonian homes, Fallingwater, the S.C. Johnson Wax Administration Building—spoke for itself, and his credentials as the son and nephew of some of the congregation’s founders surely helped as well.

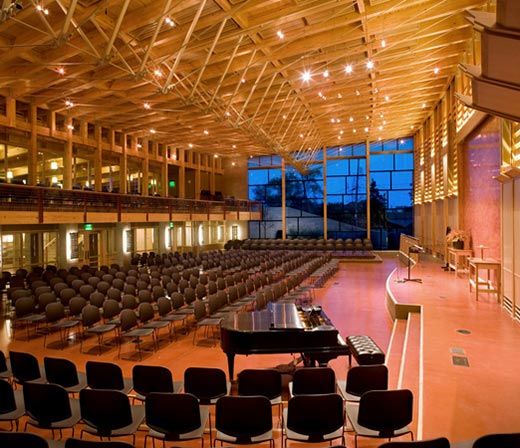

His design—the Church of Tomorrow, with its V-shaped copper roof and stone-and-glass prow—was a dramatic departure from the recognizable ecclesiastical forms of bell tower, spires and stained glass. Wright’s was steeple, chapel and parish hall all in one.

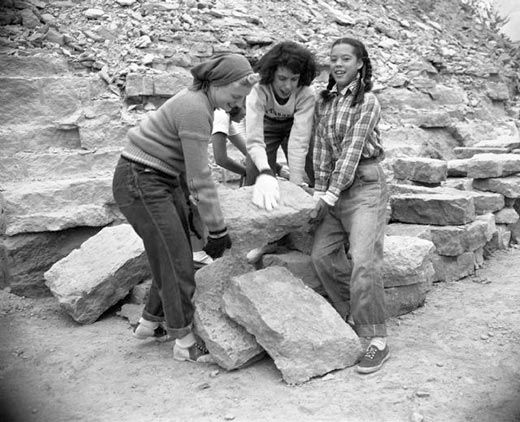

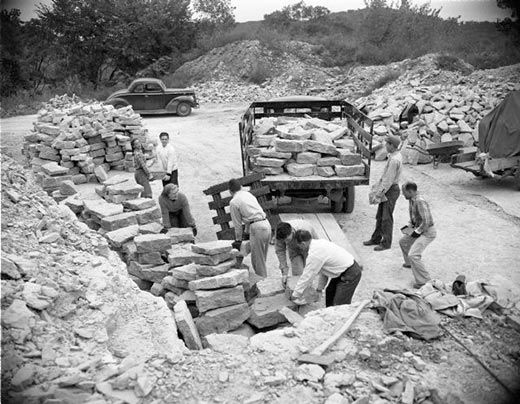

The stone for the Meeting House came from a quarry along the Wisconsin River. Wright advocated for the use of local materials in his writings. In 1939, in a series of lectures later published as An Organic Architecture, Wright shared his philosophy that architects should be “determining form by way of the nature of materials.” Buildings, he believed, were to be influenced by and clearly of their place, integrated with their environment in terms of siting as well as materials.

In 1951, with the congregation’s coffers essentially depleted after overruns tripled the cost of the construction to over $200,000, the 84-year-old architect gave a fund-raising lecture—modestly titled “Architecture as Religion”—at the barely finished building. “This building is itself a form of prayer,” he told the gathering. He raised his arms, forming two sides of a triangle.

What quickly became a local icon was, in 1973, placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2004, Wright’s First Unitarian Society Meeting House was declared a National Historic Landmark.

“Without question, one of the reasons this congregation is as strong as it is, is because of this building,” says Tom Garver, a member of the Friends of the Meeting House. “The principal problem with this building is that we filled it up.”

By 1999, as the 1,100 members had outgrown a space built for 150, the congregation debated whether to expand the building or create a satellite congregation. The decision to keep the community intact and on its original site was motivated by the congregation’s deeply rooted environmental ethic—“respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part”—contained in the seventh principle of the Unitarian Universalist Association. Their new building needed to be, in Parish Minister Michael Schuler’s words, a “responsible response” to global warming and limits to our resources.

The congregation chose a local firm, Kubala Washatko Architects, to design the $9.1 million green building with a 500-seat sanctuary and classrooms; an additional $750,000 would go toward renovating and remodeling the original structure.

John G. Thorpe, a restoration architect and a founder of the Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust in Oak Park, Illinois, says there are few additions to Wright’s institutional or commercial buildings. He cites the Guggenheim’s addition as one example and notes that the Meeting House actually had two previous additions, in 1964 and 1990.

“We’ve always had a high degree of respect for his body of work,” says Vince Micha, project architect for Kubala Washatko. “He was pretty daring and willing to do the untested. That takes a great deal of courage and self-confidence and a bit of ego. You end up with some pretty astonishing results.”

The architects assembled a panel of Wright experts, including Thorpe, to comment on their designs. Early plans included massive chimneys and triangular spaces echoing those in Wright’s design. The alternative was to counter his sharp angles with a gentle curve.

“The arc was the purest, quietest, simplest form to use in relation to the intense geometry in the Wright building,” says Micha. The architects eventually took advantage of the south-sloping site, placing the mass of the addition below the entrance level. The top floor seems to hug the earth, as does Wright’s building.

“If you’re going to touch it and add onto it, you must respect it,” says Thorpe. “Kubala Washatko was sensitive enough to end up with a design that does that.”

Micha calls the area where the two buildings are joined together “a really tender spot.” Glass walls topped by a glass roof slid underneath the broad eave of Wright’s roof provided the solution. “It sort of created this hyphen between the two structures.”

Windows running the length of the upper-level space dominated by glass, steel, cable wire and red-stained concrete floors (a shade matching Wright’s signature Cherokee red) are accented by red pine support posts from the Menominee tribal lands, a renowned sustainable forestry project in northeastern Wisconsin. As with the limestone used in Wright’s original structure, local products were used in the addition.

Kubala Washatko and other architects practicing sustainable design today rely on local materials to avoid the negative environmental impact of transporting products over long distances. For Wright, materials indigenous to a place had value since they required no additional decoration; the ornament was within. “He wanted it laid up in the way you would find it in nature,” says Garver of Wright’s use of stone in his Meeting House.

The new windows are flush to the floor, an approach similar to the one Wright used in the loggia of his landmark building. “He runs window into stone—there’s no elaborate framing,” says Garver of Wright’s technique. “It makes ambiguous what’s inside and outside.” Bringing light into a space was critical in Wright’s theory of organic architecture, for it connected the interior with nature.

Does all this make Wright a green architect?

“He was essentially green because he believed in the environment. But I wouldn’t call him green,” says Jack Holzhueter, a local historian who lived for a time in Jacobs II, Wright’s pioneering passive solar home. “To attach that label to him is not correct because we did not have that term then. He created structures that would now be called ‘toward green.’”

“He designed his buildings to cooperate with the environment,” adds Holzhueter. “He also understood the solar capacity of a building.” He knew that broad eaves would keep the sun from warming a house on a summer day, that the shelter of those eaves would cut the wind.

These principles found expression in the addition: Kubala Washatko oriented it to maximize passive solar gain; the green roof’s 8-foot overhang helps cool the building naturally.

In-floor radiant heating, which is favored by today’s green architects and a component of Kubala Washatko’s design, is incorporated in Wright’s original Meeting House. “He was trying to lower heating costs,” says Holzheuter. “Environmental responsibility was not something even talked about in those days.”

The 21,000-square-foot addition opened last September; in January, the project received a LEED Gold rating. Thanks to green features such as a geothermal heating and cooling system and a “living roof” of plants that control stormwater runoff from the site, the building is projected to use 40 percent less energy and 35 percent less water than a similar-size, conventionally built structure.

The congregation’s carbon footprint was another one of the main factors in their decision to stay where they were. “Moving to a new site on virgin piece of land would have been the exact wrong thing to do,” says Micha, reflecting on the importance the congregation placed on the original site, with its proximity to bus lines and bike paths.

By contrast, Wright was definitely not green in terms of his perspective on development density. At the time of its construction, the Meeting House was bordered by the University of Wisconsin’s experimental agricultural fields. Wright had urged the congregation to build even farther away: “Well, we have gone afield—not far enough, but at least far enough to valiantly state a principle of growth to which our civilization must awaken and soon consciously act: decentralization.”

Despite the differences, both the original building and its addition share similar inspiration in the grounds of Wisconsin. As Wright wrote in 1950 about the Meeting House, “Nothing is so powerful as an idea. This building is an idea.”