A Historian’s Quest to Unravel the Secrets of Mary Seacole, an Innovative, Long-Overlooked Black Nurse

During the Crimean War, the Jamaican businesswoman operated a storehouse and restaurant that offered food, supplies and medicine to British soldiers

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7e/0c/7e0c561c-d318-4139-9d8e-56c6a9edc534/seacole.jpg)

It had been an arduous seven months since British forces landed on the Crimean Peninsula with their French allies in September 1854. Here they still were, dug in outside Sevastopol, thousands of miles from home on this peninsula at the southernmost tip of the Russian Empire.

Having endured three terrible battles with their Russian foes, the British Army was still reeling after a bitter and devastating winter. Thanks to the scandalous incompetence of the British Commissariat, thousands of men in the rank and file had died of frostbite, hypothermia, malnutrition and gastrointestinal disease. But the new year had brought hope and the first trickle of much-needed supplies of food, medicine and warm clothes from England.

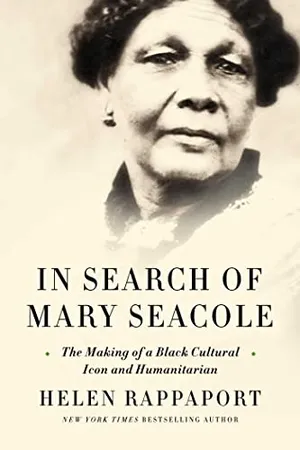

In Search of Mary Seacole: The Making of a Black Cultural Icon and Humanitarian

From New York Times bestselling author Helen Rappaport comes a superb and revealing biography of Mary Seacole that is testament to her remarkable achievements and corrective to the myths that have grown around her.

It also brought something unexpected to cheer the spirits of the beleaguered British Army. On March 9, 1855, a small announcement was made at the very end of a long dispatch by William Howard Russell, special correspondent for the London Times, who had been embedded throughout with British troops outside Sevastopol. As he noted, “Inter alia, we are to have an hotel at Balaclava. It is to be conducted by ‘Mrs. Seacole, late of Jamaica.’”

When Russell’s dispatch was syndicated across the British press, the announcement provoked a degree of bafflement; nearly every paper amended the sex of the entrepreneur in question to “Mr. Seacole.” Russell’s “Mrs. Seacole” must have been a misprint, surely? How could any respectable woman possibly entertain setting up a hotel at the seat of war—and alone and unaccompanied at that?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/68/46/6846ef2e-4d8b-4857-973a-39f3d6476c44/6b.jpg)

Events would soon show, however, that one very determined Mary Seacole was most definitely on a 3,000-mile journey from England all the way to the Black Sea, although there would be no “hotel,” per se, and certainly not at Balaclava, a supply port on the Black Sea. Instead, Seacole’s British Hotel—initially envisioned as “a mess table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers”—became a makeshift canteen and storehouse offering food, supplies and medicine to war-weary soldiers.

It was enough of a surprise that any woman should undertake such a venture. But no one in 1855 could have anticipated that the lady in question would be Black. The Victorian popular perception of Black people in the 1850s was pretty much confined to anti-slavery literature of the Uncle Tom’s Cabin variety. Yet against all the odds—of her sex, ethnicity and time—when no Black person in Britain held any public office or position of authority, Seacole would launch herself into the heart of the war effort, and with it earn herself a unique place in the British public’s consciousness.

That brief notice in March 1855 would be the first of many sightings on the Crimean Peninsula of Seacole—a Jamaican caregiver and nurse, herbalist, sutler, humanitarian and patriot—over the next 16 months. By the time British troops left in July 1856, everybody in Crimea knew Mrs. Seacole, or, as she was better known, “Mother Seacole.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/7a/7c7a8ab5-5a50-4af9-84f5-f1c0f67fc1cd/1b.jpg)

Not only that, but the British people back home knew of her Crimean exploits, too. Thanks to extensive press coverage of the war—the result of some fine on-the-ground reporting by Russell and others—and the many letters home from their men, they knew about the efficacy of Seacole’s Jamaican herbal remedies for dysentery and cholera; her skill with stitching a wound, bandaging injuries and dealing with frostbite; her wonderful stews and Christmas puddings; and most important of all, her compassion and absolute devotion to her “sons” of the British Army.

By the end of the Crimean War, Mother Seacole had become the archetype of the loyal colonial subject doing her bit for the British war effort—the embodiment of Christian kindness, compassion and generosity of spirit. Indeed, searching through hundreds of collections of letters, diaries and newspaper accounts of the war, one finds that only one other woman during that time was accorded as much coverage: Seacole’s white female nursing contemporary, Florence Nightingale. For, in her way, as Reynolds’s Newspaper observed on June 14, 1857, Seacole, like Nightingale, was “A Real Crimean Heroine.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3c/1d/3c1dfa45-40fe-45ef-9716-e868366363ac/3b.jpg)

There is no doubt that from the late 1850s to her death in 1881, Seacole was the most famous Black woman in the British Empire. Indeed, until she was voted Greatest Black Briton in 2004, only the Trinidadian pianist Winifred Atwell and the Welsh mixed-heritage singer Shirley Bassey enjoyed an equivalent celebrity, though their popularity only grew after the Second World War.

Over the years, when speaking about Seacole, I have tried to impress on people just how extraordinary and exceptional her achievements and fame were in the context of 19th-century white Victorian Britain. There simply was nobody quite like her. The nearest modern-day equivalent in terms of the national acclaim accorded a woman of color, who was also of Jamaican heritage, is probably the tremendous reception given to Kelly—now Dame Kelly—Holmes after she returned from the Athens Olympics in 2004 with two gold medals for the women’s 800 and 1,500 meters, the first British woman of color to achieve this double.

Early in 1857, while riding on the crest of her popularity and to get herself out of debt, Seacole sat down to write her memoirs in an attic room in Soho Square in London. She had served Britain with loyalty and diligence and felt that the time had come for her to receive due recognition of that fact. The account she published—Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands—was a catchy populist title that became an instant bestseller, but it has also created problems for the biographer. People assume that this is Seacole’s autobiography, but it is nothing of the sort. Her book reveals virtually no details of its author’s life before 1850.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d6/c4/d6c478d1-cd6f-4108-b361-498eecc1b9cd/mary_seacole_natinoal_portrait_gallery.jpg)

To make up for this, one might imagine, given Seacole’s celebrity in mid-Victorian Britain, that a considerable archive of personal detail has accrued from that period and added to our knowledge beyond that slim book’s 200 pages. Sadly, this is not the case: With Seacole, most of her personal story begins and ends with what she tells us in Wonderful Adventures. We come away from it knowing next to nothing about her early life—her parents, her siblings, and the complex network of friends and family back home in Jamaica. This is because Seacole left us no paper trail; evidence of almost all the key landmarks in her life prior to the war is missing, beyond the publicly accessible documents of her marriage, her death, her will and census returns.

So, how does one begin to reconstruct a life that is virtually uncharted for the first 45 years? This has been the enormous challenge of writing Seacole’s biography, for even with the republication of the Wonderful Adventures—after 127 years—in 1984, her account is still the sole primary source. But it only takes us up to her return to England in July 1856 and is full of gaps, puzzles, faux-modest evasions and glaring omissions.

The challenge for the biographer is to penetrate beyond Seacole’s carefully constructed and controlled self-image. Her book is a brilliant piece of PR, but it hides so many secrets from us. It therefore comes as something of a surprise to me, still, that, thanks to an insatiable curiosity about Seacole, I have been able to unearth as much as I have: the names of her parents and five half-siblings, details of her life in Jamaica, potential candidates for the father of her illegitimate daughter.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6d/42/6d42532d-c51c-434b-944e-f0a0c0f0f957/5b.jpg)

For me, it really has been a mission, born of a desire to reconstruct the story of a woman of color who was obliged by the racial, social and moral attitudes of her time to omit or obfuscate so much of the detail of her personal life, as well as her true attitude to the white establishment that for all too short a time allowed her to take center stage. To get to this level of truth and dig out every possible vestige of evidence relating to her life has consumed me at times and still leaves me endlessly wishing “If only I knew…,” “If only I could verify this…,” “If only there was more.”

Excerpted from In Search of Mary Seacole The Making of a Black Cultural Icon and Humanitarian by Helen Rappaport. Published by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2022 by Helen Rappaport. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/helen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/helen.png)