A Human Rights Breakthrough in Guatemala

A chance discovery of police archives may reveal the fate of tens of thousands of people who disappeared in Guatemala’s civil war

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/documents-Guatemala-police-station-archive-631.jpg)

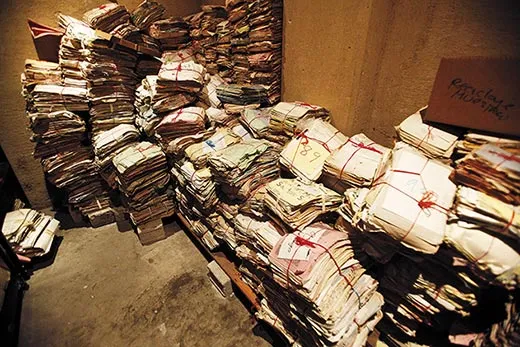

Rusting cars are piled outside the gray building in a run-down section of Guatemala City. Inside, naked light bulbs reveal bare cinder-block walls, stained concrete floors, desks and filing cabinets. Above all there is the musty odor of decaying paper. Rooms brim with head-high heaps of papers, some bundled with plastic string, others mixed with books, photographs, videotapes and computer disks—all told, nearly five linear miles of documents.

This is the archive of the former Guatemalan National Police, implicated in the kidnapping, torture and murder of tens of thousands of people during the country's 36-year civil war, which ended in 1996. For years human rights advocates and others have sought to hold police and government officials responsible for the atrocities, but very few perpetrators have been brought to trial because of a lack of hard evidence and a weak judicial system. Then, in July 2005, an explosion near the police compound prompted officials to inspect surrounding buildings looking for unexploded bombs left from the war. While investigating an abandoned munitions depot, they found it stuffed with police records.

Human rights investigators suspected that incriminating evidence was scattered throughout the piles, which included such minutiae as parking tickets and pay stubs. Some documents were stored in cabinets labeled "assassins," "disappeared" and "special cases." But searching the estimated 80 million pages of documents one by one would take at least 15 years, experts said, and virtually no one in Guatemala was equipped to take on the task of sizing up what the trove actually held.

That's when investigators asked Benetech for help. Founded in 2000 in Palo Alto, California, with the slogan "Technology Serving Humanity," the nonprofit organization has developed database software and statistical analysis techniques that have assisted activists from Sri Lanka to Sierra Leone. According to Patrick Ball, the organization's chief scientist and director of its human rights program, the Guatemalan archives presented a unique challenge that was "longer-term, more scientifically complex and more politically sensitive" than anything the organization had done before.

From 1960 to 1996, Guatemala's civil war pitted left-wing guerrilla groups supported by Communist countries, including Cuba, against a succession of conservative governments backed by the United States. A 1999 report by the United Nations-sponsored Guatemalan Commission for Historical Clarification—whose mandate was to investigate the numerous human rights violations perpetrated by both sides—estimated that 200,000 people were killed or disappeared. In rural areas, the military fought insurgents and indigenous Mayan communities who sometimes harbored them. In the cities, the National Police targeted academics and activists for kidnapping, torture and execution.

Although the army and the National Police were two separate entities, the distinction was largely superficial. Many police officers were former soldiers. One police official told the Commission for Historical Clarification that the National Police took orders from military intelligence and had a reputation for being "dirtier" than the army. The National Police was disbanded as a condition of the 1996 Guatemalan peace accords and replaced with the National Civilian Police.

The archive building is a very different place depending on which door one enters. One leads to the rooms filled with musty paper. Another opens on to the hum of fans and the clack of keyboards from workrooms and offices. Young workers in matching tan coats stride down brightly lit hallways, where row after row of metal shelves hold hundreds of neatly labeled file boxes.

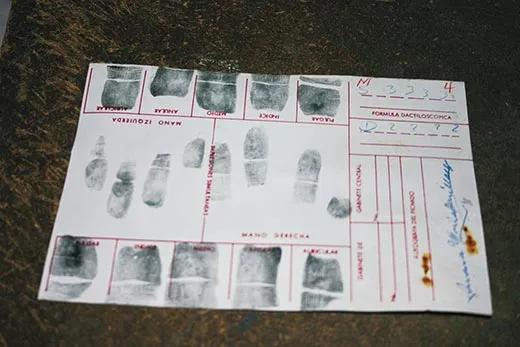

Benetech's first task was to get a sense of what the archive held. Guided by randomized computer instructions, workers withdrew sample documents: Take a paper from such and such a room, that stack, so many inches or feet deep. The more samples that are collected, the more accurately the researchers can estimate what the entire archive holds. Following this method, the investigators avoid charges from critics that they are selecting only incriminating documents.

In one room, three women in hairnets, gloves and painters' breathing masks are bent over a table. One brushes a typewritten document yellowed with age. After each document is cleaned, it is digitally scanned and filed. The Guatemalan researchers place all the documents into storage. Some documents—the ones randomly selected by Benetech—will be entered into a database called Martus, from the Greek word for "witness." Martus is offered free by Benetech online to human rights groups, and since 2003 more than 1,000 people from more than 60 countries have downloaded it from the group's Web site (www.martus.org). To safeguard the information stored in Martus, the database is encrypted and backed up onto secure computer servers maintained by partner groups worldwide.

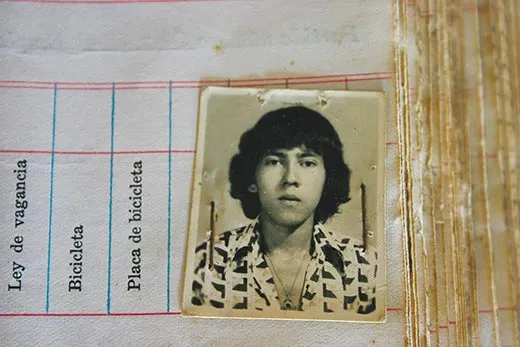

Working with an annual budget of $2 million donated by European countries, researchers and technicians have digitized eight million documents from the archive, and cleaned and organized another four million. Based on the evidence collected so far, there is "no doubt that the police participated in disappearances and assassinations," says Carla Villagran, a former adviser to the Project to Recover the Historic Archives of the National Police. In some cases the information is explicit; in others, conclusions are based on what the documents don't contain. For example, a name that disappears from an official list of prisoners might mean the person was executed.

As the details of daily reports and operational orders accumulate in the Martus database, a larger picture has emerged, allowing investigators to understand how the National Police functioned as an organization. "We're asking, ‘What's going on here?'" says Ball. Did the police get their orders directly from military intelligence or senior officials within the police force? Did mid-level officials give the orders without consulting superiors? Or did individual police officers commit these acts on their own initiative?

Ball insists that Benetech's job is to "clarify history," not to dictate policy. Guatemalan President Álvaro Colom showed his support with a visit to the archive last year. Still, "in this country, it has become dangerous to remember," says Gustavo Meoño, director of the archive project. There has been at least one attempt to firebomb the archive. Not everyone is eager to dig up the recent past, especially police—some still serving on active duty—who could be implicated in crimes. But at the very least, the researchers hope to give closure to victims' relatives and survivors. "If you have an official document that proves what you've been saying is true," Villagran says, "it's more difficult for anyone to say that you're lying about what happened to you, your family and the ones you loved." Villagran's voice cracks as she tells how her husband was kidnapped and then disappeared during the war.

This past March, Sergio Morales, the Guatemalan government's human rights ombudsman, released the first official report on the police archives project, "El Derecho a Saber" ("The Right to Know"). Though many human rights watchers had expected sweeping revelations, the 262-page report mostly just described the archive. Ball was among those disappointed, though he hopes a second report currently under development will include more details.

Yet the report did cite one specific case—that of Edgar Fernando García, a student who was shot in 1984, taken to a police hospital and never heard from again. (García's widow is now a congresswoman.) Based on evidence recovered from the archive, two former members of a police unit linked to death squads were arrested, and arrest orders have been issued for two other suspects. It was an alarming precedent for those who still could be implicated: the day after the report's release, Morales' wife was kidnapped and tortured. "They are using violence to spread fear," Morales told newspapers.

The question about what to do with future findings remains open. "Prosecutions are a great way of creating moral closure—I've participated in many," says Ball. "But they aren't what will change a country." In his view, understanding how the National Police went bad and preventing it from happening again—"that's real improvement."

The work at the archive is expected to continue. Villagran hopes to have another 12 million documents digitized over the next five years. Meanwhile, the databases have been made available to Guatemalan citizens and human rights groups everywhere, says Ball. "Now it's the world's job to dig through the material and make sense of it."

Julian Smith's book Chasing the Leopard will be published in summer 2010.