A Whole Town Under One Roof

We’re moving on up—visions of a self-contained community within a 1,000-foot tall skyscraper

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201111181230181925-Jan-18-Times-Signal-Zanesville-OH-470x251.jpg)

The January 18, 1925, Zanesville Times Signal (Zanesville, Ohio) ran an article about a proposed 88 story skyscraper in New York. Titled “How We Will Live Tomorrow,” the article imagined how New Yorkers and other city-dwellers might eventually live in skyscrapers of the future. The article talks about the amazing height of the proposed structure, but also points out the various considerations one must make when living at a higher altitude.

The article mentions a 1,000 foot building, which even by today’s standards would be quite tall. The tallest building in New York City is currently the Empire State building at 1,250 feet. Until September 11, 2001, the North Tower of the World Trade Center stood as the tallest building in New York City at 1,368 feet tall. Interestingly, the year this article ran (in 1925) was the year that New York overtook London as the most populous city in the world.

The contemplated eighty-eight-story building, 1000 feet in height, which is to occupy an entire block on lower Broadway, may exceed in cubical contents the Pyramid of Cheops, hitherto the largest structure erected by human hands.

The Pyramid of Cheops was originally 481 feet high, and its base is a square measuring 756 feet on each side. The Woolworth Building is 792 feet in heigh, but covers a relatively small area of ground.

The proposed building, when it has been erected will offer to contemplation some rather remarkable phenomena. For instance, on the top floor an egg, to be properly boiled, will require two and a half seconds more time than would be needed at the street level.

That is because the air pressure will be less than at the street level by seventy pounds to the square foot, and water will boil at 209 degrees, instead of the ordinary 212. In a saucepan water cannot be heated beyond boiling point, and, being less hot at an altitude of 1000 feet, it will not cook an egg so quickly.

When one climbs a mountain one finds changes of climate corresponding to what would be found if one were to travel northward. Thus, according to the reckoning of the United States Weather Bureau, the climate on top of the contemplated eighty-eight-story building will correspond to that of the Southern Berkshires in Massachusetts.

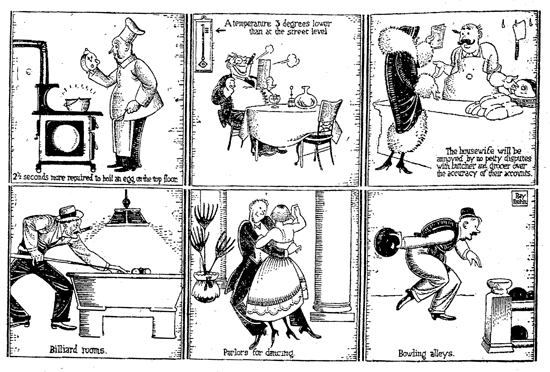

The newspaper ran a series of illustrations to accompany the article that demonstrate the communal features of skyscraper living and new considerations (however ridiculous) of living at 1,000 feet. The skyscraper was imagined to feature billiard rooms, parlors for dancing and bowling alleys. One of the illustrations explains that “the housewife will be annoyed by no petty disputes with butcher and grocer over the accuracy of their accounts.” The latter is a reference to the fact that meals will no longer be prepared at home, but “bought at wholesale rates by a manger, or by a committee representing the families of the block, and the cooks and other servants employed to do the work tend to everything, relieving the housewives of all bother.”

Features of the skyscraper of the future (1925)

The article looked to history for perspective on what wonders the next hundred years of skyscraper living may bring:

Compare the New York of today with what it was a century ago. May one not suppose that a century from now it will have undergone a transformation equally remarkable? Already the architects are planning, in a tentative way, buildings of sixty or seventy stories that are to occupy entire blocks, providing for all sorts of shops and other commercial enterprises, while affording space for the comfortable housing of thousands of families. Such a building will be in effect a whole town under one roof. The New York of today has great numbers of apartment houses. It has multitudes of family dwellings. The whole system must before long undergo a radical change. A block system of construction will replace it, achieving an economy of space which is an inexorable necessity. It is the only system under which the utmost possible utilization of ground area can be obtained.

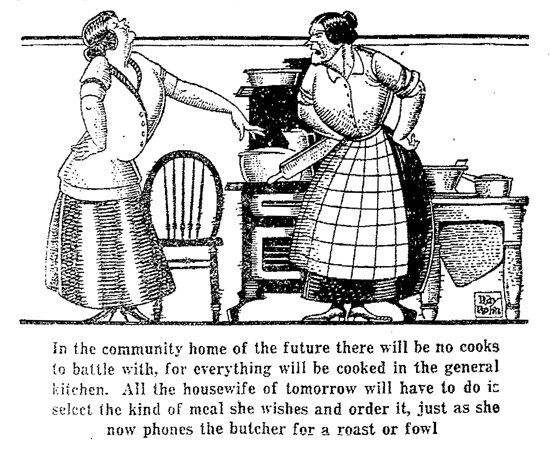

Predictions of communal kitchens in the future were quite popular in utopian novels of the late 19th century, like Edward Bellamy’s 1888 tome “Looking Backward.” But this 1925 vision of tomorrow’s kitchen shifts focus to the kind of ordering out that we may be more familiar with today. The illustration contends that “all the housewife of tomorrow will have to do is select the kind of meal she wishes and order it, just as she now phones the butcher for a roast or fowl.”

Community home and kitchen of the future

Interestingly, the pneumatic tube still rears its head in this vision of urban living in the future. The Boston Globe article from 1900 that we looked at a few weeks ago included predictions of the pneumatic tube system Boston would employ by the year 2000. Delivery of everything from parcels to newspapers to food by pneumatic tube was a promise of the early 20th century that would nearly die during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

On a recent occasion the possibilities of the pneumatic tube for the transportation of eatables was satisfactorily demonstrated by the Philadelphia Post-office, which sent by this means a hot dinner of several courses a distance of two miles. For the community block a trolley arrangement might be preferred, with a covered chut and properly insulated receptacles, lined with felt, will keep foods at a piping temperature for a dozen hours.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)