A Year of Hope for Joplin and Johnson

In 1910, the boxer Jack Johnson and the musician Scott Joplin embodied a new sense of possibility for African-Americans

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Great-Expectations-Jack-Johnson-Scott-Joplin-631.jpg)

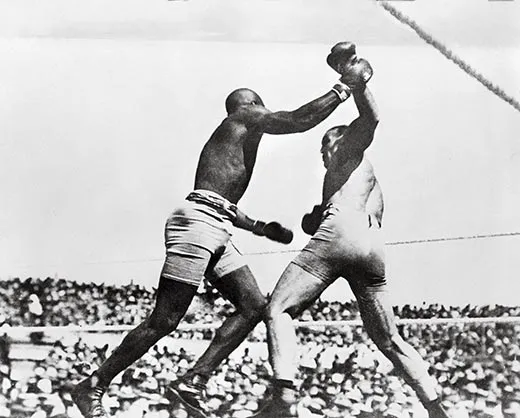

On that fourth of July afternoon 100 years ago, the eyes of the world turned to a makeshift wooden arena that had been hastily assembled in Reno, Nevada. Special deputies confiscated firearms, and movie cameras rolled as a crowd estimated at 20,000 filled the stands surrounding a boxing ring. The celebrities at ringside included fight royalty—John L. Sullivan and James “Gentleman Jim” Corbett—and the novelist Jack London. For the first time in U.S. history, two champions—one reigning, the other retired but undefeated—were about to square off to determine the rightful heavyweight king of the world. But more than a title was at stake.

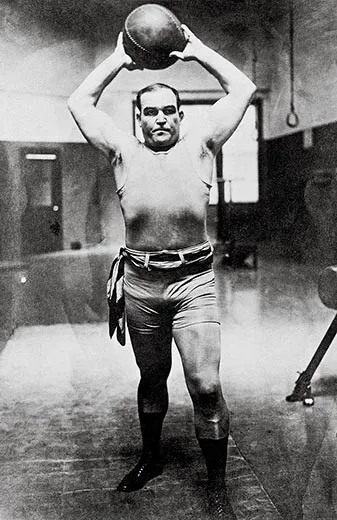

In one corner stood James Jackson Jeffries, the “Boilermaker,” who had retired undefeated six years earlier to farm alfalfa in sunny Burbank, California. The Ohio native had lived in Los Angeles since his teenage years, fighting his way up the ranks until he defeated the British-born Bob Fitzsimmons for the heavyweight championship in 1899. But now, at 35, Jim Jeffries was long past his prime. Six feet one and a half inches tall, he weighed 227 pounds, only two above his old fighting weight—but he had shed more than 70 to get there.

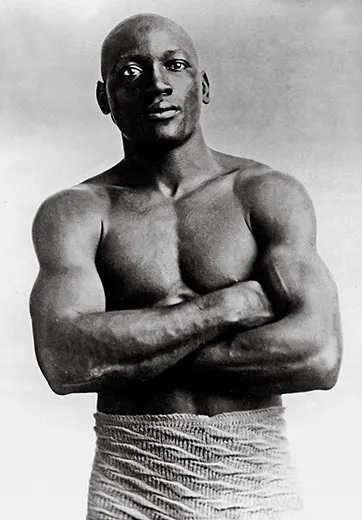

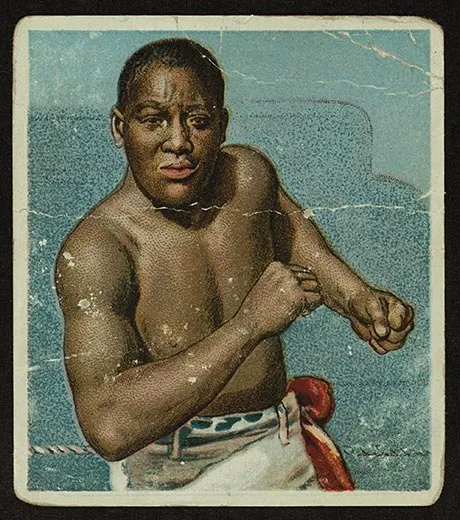

In the other corner was John “Jack” Arthur Johnson, the “Galveston Giant,” who had taken the title a year and a half before from Tommy Burns in Sydney, Australia, beating the Canadian fighter so badly that the referee stopped the fight in the 14th round. At 206 pounds, Johnson was lighter than Jeffries, but he was also three years younger, only an inch and a quarter shorter and immeasurably fitter. His head was shaved and his smile flashed gold and everything about him seemed larger than life, including his love of clothes, cars and women. Johnson had everything in his favor except that he was African-American.

A New York Times editorial summed up a common view: “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than physical equality with their white neighbors.” Jeffries was blunter: “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.”

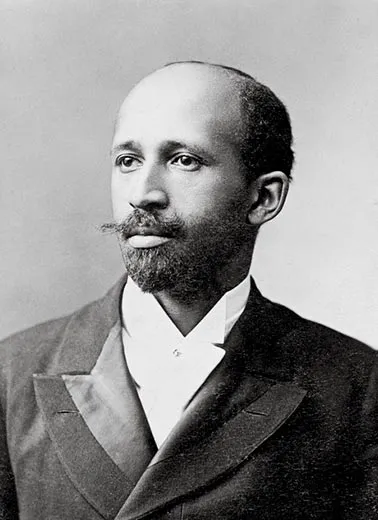

One of the nation’s first celebrity athletes, Jack Johnson also provided a rough foreshadowing of the political theories of a 42-year-old educator from Great Barrington, Massachusetts, named W.E.B. Du Bois. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was the first African-American to receive a PhD from Harvard and was a founder of the new National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He had concluded that to achieve racial equality, black people would first have to seize political power by organizing, demanding their rights and not backing down.

Such were the stakes when the bell rang for the first round of what would be called the Fight of the Century.

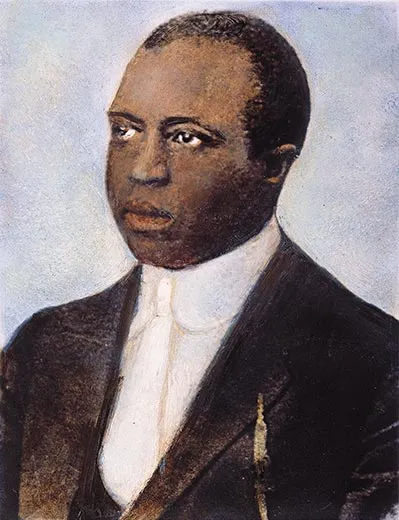

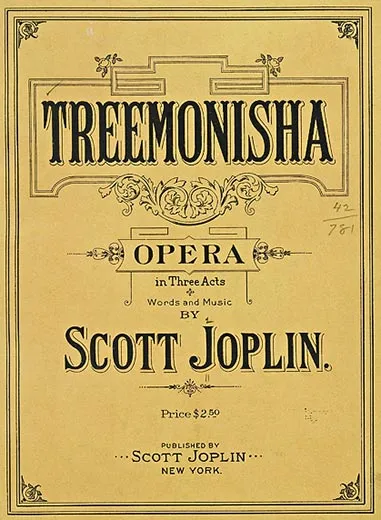

At about the same time, another African-American was making history on the other side of the country. In a boardinghouse at 128 West 29th Street in New York City—a block from Tin Pan Alley—Scott Joplin was feverishly putting the finishing touches on the libretto and score of an opera he was certain would be his masterpiece: Treemonisha.

A mild-mannered, self-effacing man who was in almost every way the opposite of Jack Johnson, Joplin had shot to fame in 1899 with the publication of the “Maple Leaf Rag,” the first million-selling piece of instrumental sheet music in America. Born in the last half of 1867 near Texarkana, Texas, to Giles and Florence Joplin, a freedman and a freeborn woman, he grew up with five siblings on the black side of town. He studied piano with a German-born teacher named Julius Weiss, who exposed him to European musical culture. Joplin left home early, kicked around Texas and the Mississippi River Valley as a saloon and bordello pianist, spent time in St. Louis and Chicago, and took music courses at the George R. Smith College in Sedalia, Missouri, about 90 miles east of Kansas City. In 1907, after a failed marriage and the death of his second wife, Joplin moved to New York.

Although Joplin did not invent ragtime—his friend Tom Turpin, a saloonkeeper in St. Louis’ Chestnut Valley sporting district in the late 19th century, was one of a few forerunners—he raised what had been a brothel entertainment into the realm of high art, taking the four-square beat of the traditional march, adding a touch of African syncopation and throwing in the lyricism of bel canto operas and Chopin nocturnes. Joplin, however, wanted more than fame as the “King of Ragtime.”

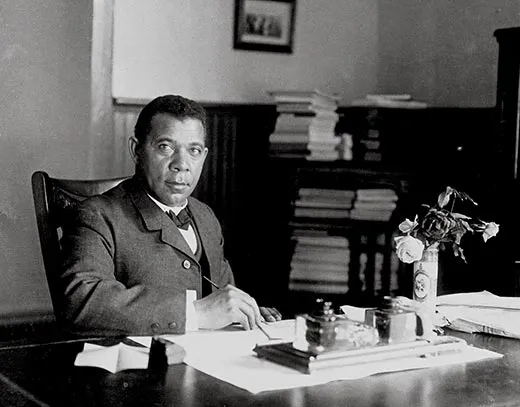

Joplin adhered to the philosophy of Booker T. Washington, who traced his rise out of bondage in the celebrated autobiography Up from Slavery and founded the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Where Du Bois, the scion of a family of New England landholders, aimed his message at what he called the “Talented Tenth” of the African-American population, Booker Taliaferro Washington advocated a by-the-bootstraps approach for the masses, one that accepted segregation as a necessary, temporary evil while African-Americans overcame the baleful legacy of slavery. Born in 1856, the son of a white man and a slave woman in Virginia, he preached that training and education were the keys to racial advancement. The Negro, he maintained, had to demonstrate equality with the European by exhibiting the virtues of patience, industry, thrift and usefulness. “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers,” he said in his famous Atlanta Compromise speech of 1895, “yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

Washington’s message was reflected in Joplin’s opera: set in the aftermath of the Civil War in Arkansas, Treemonisha told the tale of a wondrous infant girl found under a tree by a newly freed, childless couple named Ned and Monisha. Educated by a white woman, the girl, Treemonisha, rises to lead her people, defeating evil conjurers who would keep them enslaved by superstition, advocating education and bringing her followers triumphantly into the light of Reason to the strains of one of Joplin’s greatest numbers, “A Real Slow Drag.”

Joplin had long dreamed of a grand synthesis of Western and African musical traditions, a work that would announce to white America that black music had come of age. With Treemonisha, he felt that goal was in his grasp.

The first decade of the 20th century followed a period of disillusion and disenfranchisement for African-Americans. Starting in 1877 with the end of Reconstruction—when Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops from former Confederate states under an agreement that had secured him the disputed presidential election of the preceding year—the promises of emancipation proved hollow as newly elected Southern Democrats passed Jim Crow laws that codified segregation. In the 1890s alone, 1,111 African-Americans were lynched nationwide.

When President Theodore Roosevelt received Booker T. Washington for dinner at the White House in 1901, black America was electrified; Joplin memorialized the event in his first opera, A Guest of Honor, now lost, and he based his rag “The Strenuous Life” on TR’s landmark 1899 speech extolling the “life of toil and effort, of labor and strife.” But the White House visit was ridiculed across the South. (Back in Sedalia, the Sentinel published a derisive poem titled “N-----s in the White House” on its front page.)

In his 1954 study The Negro in American Life and Thought, Rayford Logan characterized the decades before the turn of the century as “the nadir” for African-Americans. The historian David Levering Lewis agrees. “It was a time of especially brutal relations between the races,” says the winner of two Pulitzer Prizes for his two-volume biography of Du Bois. “By 1905, segregation has been poured in concrete, as it were. Blacks can’t ride buses, go to vaudeville shows or the cinema unless they sat in the crow’s nest. [Blacks and whites] begin to live parallel lives, although not on an even plane.”

By the end of the decade, black Americans had begun the Great Migration northward, leaving the old Confederacy for the industrial cities of the North. Between 1910 and 1940, an estimated 1.75 million black Southerners would uproot themselves and settle not only in New York, Philadelphia and Chicago, but also in such smaller cities as Dayton, Toledo and Newark. “A new type of Negro is evolving—a city Negro,” the sociologist Charles S. Johnson would write in 1925. “In ten years, Negroes have been actually transplanted from one culture to another.” That same year, the intellectual Alain Locke said the “New Negro” had “renewed self-respect and self-dependence” and was slipping “from under the tyranny of social intimidation and...shaking off the psychology of imitation and implied inferiority.”

That tide of hope was just starting to rise in 1910, as early-arriving black migrants discovered opportunities previously denied them. Sports and entertainment long existed on the margins of polite society, where they provided immigrants—often marginalized and despised—a means of clawing their way toward the American dream. Now, it seemed, African-Americans might tread the same path.

The first all-black musical on Broadway, Clorindy; or, the Origin of the Cakewalk, had been a sensation in 1898, and its composer, Will Marion Cook, would have another triumph five years later with In Dahomey. Although largely forgotten today, Cook, an African-American from Washington, D.C., was a pioneer: he had been educated at Oberlin College and in Berlin, where he studied violin at the Hochschule für Musik; he then worked with Antonin Dvorak at the National Conservatory of Music in New York City.

After Clorindy’s opening-night triumph at the Casino Theatre at West 39th Street and Broadway, Cook recalled: “I was so delirious that I drank a glass of water, thought it wine and got glorious drunk. Negroes at last were on Broadway, and there to stay....We were artists and we were going a long way. We had the world on a string tied to a runnin’ red-geared wagon on a down-hill pull.”

True, the ride would be rough—at the height of a Manhattan race riot on August 15, 1900, whites had singled out black entertainers—but by 1910 it at least seemed underway. “For a moment it indeed looked like African-Americans were arriving on Broadway in numbers as large as Jews, and that’s very important,” says historian Lewis. “It led to some aspiration, in terms of poetry and music, that could indeed soften the relations between the races.”

Sports were not so different, especially boxing, where the races mingled relatively freely. Peter Jackson, a black native of St. Croix, fought leading black contenders such as Joe Jeannette and Sam McVey, both contemporaries of Jack Johnson, and fought Gentleman Jim Corbett to a 61-round draw in 1891. Even though blacks and whites met in the ring, the heavyweight title was considered sacrosanct, a symbol of white superiority. Thus Johnson’s demolition of Tommy Burns in 1908 stunned the sporting world, which shunned him as the legitimate champ. Since Jeffries had retired undefeated, the only way Johnson could place his title beyond dispute was to beat Jeffries in the ring.

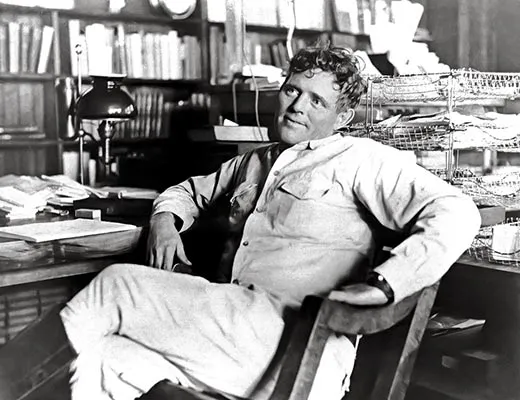

“With the rise of modern heavyweight champions, race was at the center of nearly every important heavyweight drama,” David Remnick, a Muhammad Ali biographer, wrote in the London Guardian’s Observer Sport Monthly in 2003. “First came John L. Sullivan, who refused to cross the color line and face a black challenger. Then came Jim Jeffries, who swore he would retire ‘when there are no white men left to fight’....Jeffries seemed to have the support of all of white America,” including, Remnick noted, the press, led by celebrated newspaperman and novelist Jack London, an occasional boxing correspondent for the New York Herald. The editors of Collier’s magazine wrote that “Jeffries would surely win because...the white man, after all, has thirty centuries of traditions behind him—all the supreme efforts, the inventions and the conquests, and whether he knows it or not, Bunker Hill and Thermopylae and Hastings and Agincourt.”

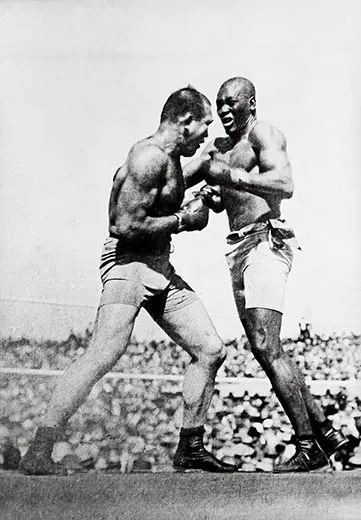

At first glance, it seems that the two men are dancing. Johnson, tall, broad-shouldered and bullet-headed, keeps his opponent at arm’s length, his gloves open. Jeffries charges, Johnson retreats, as agile as the young Ali (when he fought under his given name, Cassius Clay), swatting away punches as if they were butterflies. “He was catching punches,” says boxing historian Bert Sugar. “Jack Johnson was perhaps the greatest defensive heavyweight of all time.”

The Johnson-Jeffries fight was of such intense interest that it was filmed to be shown in movie theaters worldwide. Three years before the federal income tax was levied, promoter Tex Rickard paid each fighter $50,000 (worth about $1.16 million in 2010) for the film rights, to go with a signing bonus of $10,000 apiece; the winner would also take two-thirds of the purse of $101,000.

Watching the film today, one sees immediately how commanding a ring general Johnson was. Once it became clear, in the early rounds, that the once-fearsome Jeffries couldn’t hurt him, Johnson toyed with his opponent, keeping up a running stream of commentary directed at Jeffries, but even more so at a not-so-gentlemanly Jim Corbett in Jeffries’ corner. Corbett had showered Johnson with racist invective from the moment the fighter entered the ring, and a majority of the crowd had joined in. Many of the spectators were calling for Jeffries to kill his opponent.

“Jack Johnson was a bur in the side of society,” notes Sugar. “His win over Tommy Burns in 1908 was the worst thing that had happened to the Caucasian race since Tamerlane. Here was Johnson, flamboyantly doing everything— running around with white women, speeding his cars up and down streets and occasionally crashing them—all of it contributed to find somebody to take him on. Jack London had written: ‘Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove that smile from Johnson’s face.’”

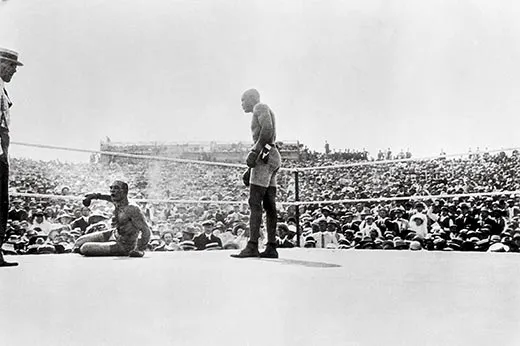

Instead, Johnson’s swift jab and eviscerating counterpunches began to take their toll as Johnson turned the tables on his tormentors. “Don’t rush, Jim. I can do this all afternoon,” he said to Jeffries in the second round, hitting the big man again. “How do you feel, Jim?” he taunted in the 14th. “How do you like it? Does it hurt?” Dazed and bleeding, Jeffries could barely keep his feet, and Corbett fell silent. In Round 15, Jeffries went down for the first time in his career. Johnson hovered nearby—there were no neutral corners in those days—and floored the former champ again the minute he regained his feet. Now a different cry went up from the crowd: Don’t let Johnson knock Jeffries out. As Jeffries went down yet again, knocked against the ropes, his second jumped into the ring to spare his man, and the fight was over. The audience filed out in near-silence as Tex Rickard raised Johnson’s arm in triumph; across America, blacks poured into the streets in celebration. Within hours scuffling broke out in cities across the country.

The next day, the nation’s newspapers toted up the carnage. The Atlanta Constitution carried a report from Roanoke, Virginia, saying that “six negroes with broken heads, six white men locked up and one white man, Joe Chockley, with a bullet wound through his skull and probably fatally wounded, is the net result of clashes here tonight.” In Philadelphia, the Washington Post reported, “Lombard Street, the principal street in the negro section, went wild in celebrating the victory, and a number of fights, in which razors were drawn, resulted.” In Mounds, Illinois, according to the New York Times, “one dead and one mortally wounded is the result of the attempt of four negroes to shoot up the town....A negro constable was killed when he attempted to arrest them.” In all, as many as 26 people died and hundreds were injured in violence related to the fight. Almost all of them were black.

In the following days, officials or activists in many localities began pushing to bar distribution of the fight film. There were limited showings, without incident, before Congress passed a law forbidding the interstate transportation of boxing films in 1912. That ban would hold until 1940.

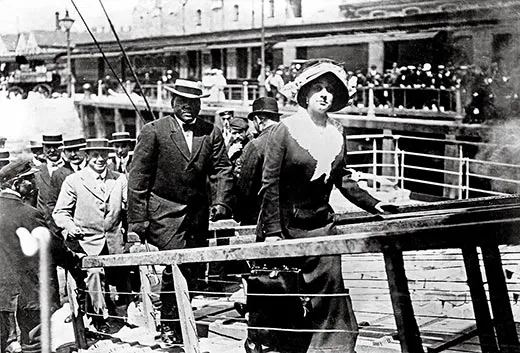

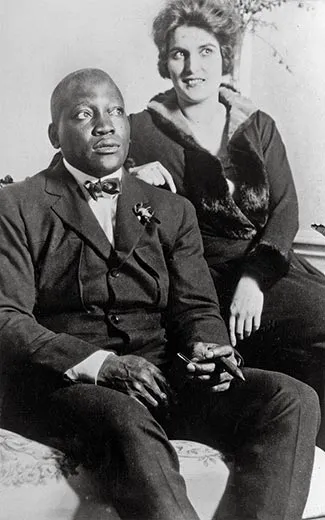

Johnson continued his flamboyant ways, challenging the white establishment at every turn. With some of the winnings from the fight, he opened the Café de Champion, a Chicago nightclub, and adorned it with Rembrandts he had picked up in Europe. In October 1910, he challenged race car driver Barney Oldfield and lost twice on a five-mile course at the Sheepshead Bay track in Brooklyn. (“The manner in which he out-drove and out-stripped me convinced me that I was not meant for that sport,” Johnson would write in his autobiography.) And he continued dating, and marrying, white women. His first wife, Etta Duryea, shot herself to death in September 1912. Later that fall, he was arrested and charged under the Mann Act, the 1910 law that prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for “immoral purposes.” (The arrest did not prevent his marriage to Lucille Cameron, a 19-year-old prostitute, that December.) Tried and convicted in 1913, he was sentenced to a year and a day in prison.

Rather than face jail, Johnson fled to France, where he defended his title against a succession of nonentities. He finally lost it in another outdoor ring under a broiling sun in Havana in 1915 to Jess Willard, a former mule seller from Kansas who had risen to become the leading heavyweight contender. Once again, the heavyweight division had a white champion.

In 1920, Johnson returned to the United States to serve his year in prison. Released on July 9, 1921, at age 43, he fought, and mostly lost, a series of inconsequential fights. In 1923, he bought a nightclub on Lenox Avenue in Harlem, Jack Johnson’s Café de Luxe; the gangster Owney Madden took it over and transformed it into the famed Cotton Club. Divorced from Lucille in 1924, Johnson married Irene Pineau, who was also white, a year later. In 1946, racing his Lincoln Zephyr from Texas to New York for the second Joe Louis-Billy Conn heavyweight title fight at Yankee Stadium, he hit a telephone pole near Raleigh, North Carolina. It was the only crash Jack Johnson failed to walk away from. He was 68.

No black man would hold the heavyweight title again until 1937, when Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, scored an eight-round knockout of James J. Braddock, the last of the Irish heavyweight champions.

In New York City, Joplin had undertaken a struggle all his own. Although he couldn’t find a publisher or backers to produce Treemonisha, the composer grew ever more determined to see his masterwork fully staged. According to King of Ragtime, Edward A. Berlin’s 1994 biography of Joplin, there had been a full-cast run-through without orchestra, scenery or costumes some time in 1911 for an audience of 17 people, and in May 1915, Joplin would hear a student orchestra play the Act II ballet, “Frolic of the Bears.” “The only orchestrally performed selection from his opera that Joplin was ever to hear,” Berlin wrote, “was apparently short of success.”

In late 1914, his health failing, Joplin moved with his third wife, Lottie Stokes, to a handsome brownstone in Harlem, where his output of piano rags dwindled to almost nothing. To make ends meet, Lottie took in boarders; in short order she turned the house over to prostitution. Joplin took himself to a studio apartment on West 138th Street and kept working. While awaiting his opera’s fate, he wrote the ineffably poignant “Magnetic Rag” of 1914, which stands as his farewell to the genre.

In October 1915, Joplin began to experience memory loss and other symptoms of what would turn out to be tertiary syphilis, most likely contracted during his youth in the Midwest. He had never been a virtuoso at the piano, and now his skills began to fade. A series of piano rolls he made in 1916 record the decline; a version of “Maple Leaf Rag” he performed for the Uni-Record company is almost painful to hear. According to Berlin, Joplin announced the completion of a musical comedy, If, and the start of his Symphony No. 1, but as his mind deteriorated along with his health, he destroyed many manuscripts, fearing they would be stolen after his death.

In January 1917 he was admitted to Bellevue Hospital, then transferred to the Manhattan State Hospital on Ward’s Island in the East River. He died at age 49 from what his death certificate listed as dementia paralytica on April 1, 1917, and was buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery in Queens. In The New York Age, a black newspaper, editor Lester Walton attributed his death to the failure of Treemonisha.

He had died too soon. A few years later, Harlem’s artistic community reached critical mass, as poets, painters, writers and musicians poured into the area. West 138th Street began to be known by a new name: Striver’s Row. The Harlem Renaissance had begun and would bear its full fruit over the next decade and into the 1930s. Says Lewis: “It was a moment missed, and yet at the same time enduring.”

In 1915, the year Johnson lost the title to Jess Willard, Booker T. Washington joined other black leaders to protest the celebratory racism of D. W. Griffith’s silent film The Birth of a Nation. Exhausted from a lifetime of overwork, Washington collapsed from hypertension in New York City and died in Tuskegee on November 14 at the age of 59.

In 1961, W.E.B. Du Bois concluded that capitalism was “doomed to self-destruction” and joined the Communist Party USA. The man who had cited as his only link to Africa “the African melody which my great-grandmother Violet used to sing” moved to Ghana. He died in 1963, at age 95.

In 1972, Treemonisha finally was given its world première, by conductor Robert Shaw and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, together with the music department of Morehouse College. “Warmth seemed to radiate from the stage to the capacity audience and back,” wrote the Atlanta Journal and Constitution’s music critic, Chappell White, and while it was clear that Joplin “was an amateur in the literary elements of opera,” his work reflected “remarkable daring and originality.” Three years later, a production by the Houston Grand Opera played for eight weeks on Broadway. And in 1976, the Pulitzer Prize committee awarded Scott Joplin a posthumous citation for his contributions to American music.

In July 2009, both houses of Congress passed a resolution urging President Obama to pardon Jack Johnson posthumously for his 1913 conviction under the Mann Act. As of press time, the White House had declined to say how the president would act.

Michael Walsh is the author of a biography of Andrew Lloyd Webber. The most recent of his several novels is Hostile Intent.