Abraham Lincoln’s Oft-Overlooked Campaign to Promote Immigration to the U.S.

A few weeks after the president delivered the Gettysburg Address, he called on Congress to welcome immigrants as a “source of national wealth and strength”

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/86/f5865425-d30a-4f8f-b69d-05f36522d3e3/lincoln-and-immigration.jpg)

Even under ideal circumstances, it would have been difficult for President Abraham Lincoln to surpass his recent address at Gettysburg. And now, with a fresh rhetorical challenge awaiting him, he fell ill. Lincoln arrived back in Washington, D.C. from Pennsylvania late on November 19, 1863, suffering from variola, a supposedly mild form of smallpox that proved severe enough to send the exhausted orator to his sickbed for weeks. By some accounts, Lincoln did not return to his White House desk until mid-December. Tellingly, the valet who tended him during his convalescence, a Black man named William H. Johnson, caught smallpox, too—and died.

Debility notwithstanding, Lincoln faced an unavoidable deadline for not only a new manuscript but also a much lengthier one. With the 38th session of the House and Senate set to convene on December 7, the president was expected to present his annual message to Congress—the equivalent of today’s State of the Union address—the following day. This would be his third such message, and the first to a Congress whose Republican strength had shriveled following setbacks in the most recent midterm elections.

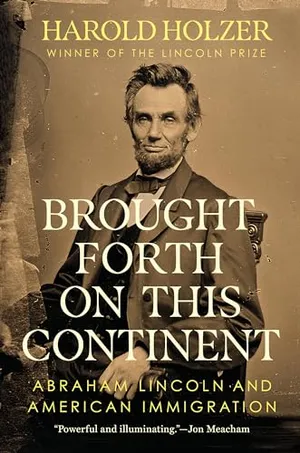

Brought Forth on This Continent: Abraham Lincoln and American Immigration

From acclaimed Abraham Lincoln historian Harold Holzer, a groundbreaking account of Lincoln’s grappling with the politics of immigration against the backdrop of the Civil War.

Nonetheless, Lincoln intended the message to include something dramatic: a historic proposal to encourage—and perhaps even financially underwrite—foreign immigration to the United States. By some accounts, Lincoln composed the entire message in bed.

The remarks at Gettysburg had been, in Lincoln’s folksy description, “short, short, short”: barely 270 words. No such brevity ever satisfied Congress. By custom, the House and Senate anticipated a detailed summary on both foreign and domestic affairs. To be expected was a full accounting of federal spending, as well as an update on the ongoing war against the Rebels. Congress would particularly desire reports on the enforcement of the president’s Emancipation Proclamation (“I shall not attempt to retract or modify [it],” he would pledge) and on the first months of African American military recruitment (which, he would report, “gave to the future a new aspect”).

Tradition also called for the president to use this yearly opportunity to specify his legislative priorities. Here is where the bedridden Lincoln summoned what strength he could muster to craft a historically bold proposal. “I again submit to your consideration,” he declared 20 paragraphs into his text, “the expediency of establishing a system for the encouragement of immigration.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/c8/56c82c5c-aa00-4b1b-a853-466e6b3d0334/lincolns_gettysburg_address_gettysburg.jpg)

Between 1830 and the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861, millions of Europeans migrated to the U.S., forever upending the demography, culture and voting patterns of the nation, especially in its teeming urban centers. In the wake of such overwhelming change, resistance to immigration and immigrants metastasized until forces arose that were determined not only to restrict foreigners from entering the country but also to disenfranchise, demonize and, occasionally, terrorize those who had already arrived, settled and earned citizenship here. And still the refugees poured across oceans and borders to reach our shores, their growing numbers inevitably challenging, and ultimately redefining, what it meant to be American.

Only when the Civil War began did foreign migration to the U.S. slow significantly. Prospective immigrants understandably shrank from the notion of abandoning one troubled country to relocate to another. To some Americans, the reduction in new foreign arrivals came as an answered prayer. For decades, immigration, particularly by Catholics, had stirred resistance, resentment and, in some cases, violence, destruction and death. Politically, these tensions split and ultimately destroyed the old Whig Party, in which Lincoln had spent most of his political career, inspiring anti-immigration nativists to form a political organization of their own. The realignment had driven many immigrants into the ranks of the Democrats, who welcomed new arrivals with a warm embrace and a swift path to citizenship and voter registration. The issue roiled the country and exposed an ugly vein of bigotry in the American body politic. And its intractability deflected mainstream attention from the country’s original sin: slavery.

Now Lincoln looked beyond the longtime national divide over immigration to propose his revolutionary idea. Although he reported in his message that refugees were “again flowing with greater freedom” into America, their numbers had yet to reach their robust, if bitterly contested, prewar levels. And the reduction was causing what Lincoln called “a great deficiency of laborers in every field of industry, especially in agriculture and in our mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals.” In other words, America could no longer rely on American workers to fill American jobs. Employers needed to look elsewhere—namely overseas—for labor.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d3/c5/d3c5a864-880a-419f-85d2-5fe23ac9b51c/germans-emigrate-1874.jpeg)

True enough, the Lincoln administration had in a sense contributed to this crisis-level “deficiency.” As many as a million men had now enrolled in the Union armed forces to fight the Confederacy, and since the spring of 1863, the newly introduced military draft had been wresting laborers from farms and factories and redeploying them into the Army. As Lincoln saw matters, their necessary absence from the home front now threatened national productivity—of civilian goods as well as war materiel. Whether the situation might ease longtime hostility to foreign laborers would be left for another day. First, Lincoln urgently wanted robust immigration to resume—even if the government had to provide the means to accelerate it.

As Lincoln forcibly argued in his message, the time had come to regard immigrants not as interlopers but as assets, not as a drain on public resources but as a “source of national wealth and strength.” He expressed it this way:

While the demand for labor is thus increased here, tens of thousands of persons, destitute of remunerative occupation, are thronging our foreign consulates and offering to emigrate to the United States if essential, but very cheap, assistance can be afforded them. It is easy to see that, under the sharp discipline of civil war, the nation is beginning a new life. This noble effort demands the aid, and ought to receive the attention and support, of the government.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/55/ee/55eebf4d-9343-431b-9035-5d6b4bfd3326/soldiers.jpeg)

Summoning his full rhetorical power, Lincoln concluded his 1863 annual message with a resounding salute to the Army and Navy, “the gallant men, from commander to sentinel, who compose them”—many of them, he might have mentioned, foreign-born—“and to whom, more than to others, the world must stand indebted for the home of freedom disenthralled, regenerated, enlarged and perpetuated.” The key words were “regenerated” and “enlarged.” At Gettysburg in November, Lincoln had spoken of the “fathers” who had “brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty.” He proclaimed, more directly than had any previous chief magistrate, that a new generation conceived elsewhere might also enjoy a “new birth of freedom” in a land other than their birthplace.

Addressing Congress in December, Lincoln shared a strong message on immigration, especially given his reduced physical vitality. Still, the result evoked the usual partisan press response. To the pro-administration New York Tribune, the message showed “wise humanity and generous impulses.” But to the hostile Richmond Examiner, its author remained a “Yankee monster of inhumanity and falsehood.” From whatever political viewpoint, nearly all of the coverage focused on Lincoln’s new plan for amnesty and reconstruction, a generous—perhaps over-generous—move to end the rebellion with the Emancipation Proclamation intact. Under the proposal, Confederate states could establish new governments after they accepted the abolition of slavery and 10 percent of their male population swore loyalty to the Union.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0a/fb/0afbf0fe-83e2-4ed0-8377-ebdbfbc9d3f8/abraham_lincoln_4271563209.jpeg)

Largely escaping notice was the president’s landmark proposal on immigration, just as the entire subject of Lincoln and immigration policy has been largely overlooked by generations of historians and biographers. Coming as it did less than a month after his oratorical zenith at Gettysburg, Lincoln’s message was quickly forgotten—and largely remains so.

Yet Lincoln’s proposal did spur prompt and consequential action on what became the first piece of proactive federal legislation to encourage, rather than discourage, immigration to the United States. Congress made sure An Act to Encourage Immigration reached the president for his signature by a doubly symbolic date: July 4, 1864. It was not only Independence Day but the third anniversary of an earlier message Lincoln had sent to a special session of Congress at the start of the war in 1861. In words that would have fit well into his new argument for immigration reform, Lincoln had urged loyalty to the government, pledging, as he put it, “to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all.” Now, for the first time, the government would openly encourage natives of the Old World to pursue such opportunity in the New.

Excerpted from Brought Forth on This Continent: Abraham Lincoln and American Immigration by Harold Holzer, to be published on February 13, 2024, by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. © 2024 Harold Holzer.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/harold2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/harold2.png)