African Europeans, Jewish Commandos of WWII and Other New Books to Read

These May releases elevate overlooked stories and offer insights on oft-discussed topics

:focal(777x396:778x397)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/0e/490ee08c-3f8e-43b3-8869-95600406d530/booksweek18.png)

Sweeping in scope and ambition, historian Olivette Otele’s newest book is one of the first comprehensive chronicles of African people’s presence on the European continent. Beginning in Roman-occupied Gaul, where the Egyptian-born Saint Maurice was reportedly executed for refusing to worship Jupiter prior to a battle, African Europeans traces its subjects’ stories across the millennia, from the 3rd century to the 21st. Along the way, Otele highlights famous and lesser-known individuals alike, balancing profiles of specific figures with a broader examination of how conceptions of race have changed over time.

“The term ‘African European’ is … a provocation for those who deny that one can have multiple identities and even citizenships, as well as those who claim that they do not ‘see color,’” writes Otele in the book’s introduction. “The aims of this volume are to understand connections across time and space, to debunk persistent myths, and to revive and celebrate the lives of African Europeans.”

The latest installment in our series highlighting new book releases explores the lengthy history of African Europeans, the wartime exploits of German Jewish commandos fighting for the British Army, a deadly treasure hunt in the Rocky Mountains, a tale of espionage and enslavement in colonial America, and the secret world of plant communication.

Representing the fields of history, science, arts and culture, innovation, and travel, selections represent texts that piqued our curiosity with their new approaches to oft-discussed topics, elevation of overlooked stories and artful prose. We’ve linked to Amazon for your convenience, but be sure to check with your local bookstore to see if it supports social distancing–appropriate delivery or pickup measures, too.

African Europeans: An Untold History by Olivette Otele

Prior to the 17th century, religion was “a far more important vector of prejudice than skin color or geographic origin,” notes the Guardian in its review of African Europeans. Faced with fewer societal constraints, some early African Europeans assumed positions of power and successfully inhabited multiple worlds simultaneously. (Just look to Roman Emperor Septimius Severus and Renaissance Duke of Florence Alessandro de’ Medici.)

Otele argues that the slave trade and rise of plantation slavery in the Americas irrevocably shifted the relationship between Europe and Africa away from one of collaboration. The 18th century, she notes, “was a time at which Black presence was severely controlled, and scientific classification of various species was employed in a bid to establish a racial hierarchy.” Physical subjugation, in turn, “was accompanied not only by a rewriting of the oppressor’s history, but also by a shaping of the story of the oppressed.”

African Europeans is organized largely chronologically, with chapters on early encounters, the Renaissance and the invention of race followed by explorations of gender roles in 18th- and 19th-century trade centers, “historical amnesia” in former German colonies, and identity politics in modern and contemporary Europe. Featuring a rich cast of characters, from 16th-century humanist poet Juan Latino to actress and artists’ muse Jeanne Duval to the Nardal sisters, who helped lay the foundations for the 1930s Négritude movement, the text reveals “the richness and variety of the African European experience,” as Publishers Weekly writes in its review.

The book “demonstrates that cross-cultural engagement is a powerful way forward to combat discrimination,” according to Otele. “Most of all, it is a celebration of long histories—African, European and global—of collaborations, migrations, resilience and creativity that have remained untold for centuries.”

X Troop: The Secret Jewish Commandos of World War II by Leah Garrett

When World War II broke out in September 1939, the United Kingdom’s government designated the roughly 70,000 Germans and Austrians living in the country as “enemy aliens.” In total, notes the U.K. National Archives, at least 22,000 expatriates were imprisoned in detention camps over the course of the war.

Among the internees were dozens of young Jewish men who’d left Europe during Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. When the British military offered these refugees an escape from the camps for “unspecified ‘hazardous duty,’ which they were told would entail extremely dangerous work that involved taking the fight directly to the Nazis,” every single one accepted, writes historian Leah Garrett in her latest book. Together, they would form one of the U.K.’s most elite—and overlooked—units: the No. 3 (Jewish) Troop of the No. 10 Commando, better known as “X Troop.”

Based on declassified military records, wartime diaries, and interviews with commandos and their families, X Troop vividly charts the special unit’s missions, from storming Pegasus Bridge on D-Day to successfully liberating a trooper’s parents’ from the Theresienstadt concentration camp to capturing escaped Nazis after the war. As Garrett explains, the commandos had “an unusual combination of skills that usually don’t go together: advanced fighting techniques and counterintelligence training” centered on their fluency in German. Instead of waiting to interrogate prisoners back at headquarters, X Troopers questioned Nazis in the heat of battle or soon after, ensuring that essential intelligence remained fresh.

Garrett’s narrative focuses on 3 of the at least 87 men who passed through X Troop’s ranks, detailing how they and their comrades shed their identities as Jewish refugees to masquerade as British soldiers. “If they were recognized as Jews,” the historian writes, “they would be killed instantly and the Gestapo would hunt down their families if they were still alive.” The unit was so shrouded in secrecy, in fact, that just six men—including Prime Minister Winston Churchill and chief of combined operations Lord Louis Mountbatten—initially knew of its existence. After the war, this aura of anonymity persisted, with many former X Troopers retaining their assumed names and rarely speaking about their experiences. Most raised their children as Anglican Christians.

X Troop seeks to spotlight its subjects’ largely unheralded wartime contributions. “By serving as commandos,” notes Garrett, “the men of X Troop not only had been able to play crucial roles in the Allied effort, but they also had been able to feel a sense of agency—and eventually personal victory—over those who had destroyed their childhoods. As refugees they had been subject to the whims of history. As X Troopers they had helped shape it.”

Chasing the Thrill: Obsession, Death, and Glory in America's Most Extraordinary Treasure Hunt by Daniel Barbarisi

Eleven years ago, art dealer Forrest Fenn stashed a chest filled with $2 million worth of gold coins and nuggets, precious gems, and pre-Hispanic artifacts somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. Over the next decade, an estimated 350,000 people joined a much-publicized hunt for Fenn’s treasure, obsessively interpreting a poem in his autobiography said to contain nine clues to its location and dedicating countless hours to the pursuit. Five died while searching; others sank their life savings into the quest or grew so frustrated that they filed court cases accusing Fenn of fraud. Then, in June 2020, the dealer made a startling announcement: “The treasure has been found.”

Journalist Daniel Barbarisi first learned of the hidden cache in 2017. Once a dedicated searcher himself, he later shifted focus to writing an account of Fenn’s trove—and the insular, sometimes-fanatical community of treasure hunters who spent years trying to find it. In Chasing the Thrill, Barbarisi weaves personal anecdotes with extensive interviews, including conversations with fervent searchers, people who lost loved ones to the hunt, skeptical scholars and Fenn himself. He offers a glimpse of the enigmatic mastermind behind the search but acknowledges the difficulty of ever truly pinpointing the former pilot’s motivations. (Fenn, for his part, said he devised the search to help people “get off their couches.”)

“Could Fenn have ever really imagined what he had set in motion that day he secreted away his chest?” asks Barbarisi in the book’s closing pages. “Had he understood all along it would make people think, believe, do? Had all of it been part of his grand plan? Or had he just liked to play games with the world, roll the dice and see what happened?”

The eccentric art dealer died at age 90 last September, three months after announcing the treasure’s recovery. A few weeks later, writing for Outside magazine, Barbarisi revealed the lucky finder’s identity: Jack Stuef, a 32-year-old medical student from Michigan who claimed that the key to the mystery had been understanding Fenn’s character through close readings of his writings and interviews.

Though Stuef declined to share the treasure’s exact location, he did allow Barbarisi to examine the chest in person. The journalist’s description of the “electric thrill” he felt upon seeing and touching the artifacts—and the lingering disappointment experienced upon realizing that the hunt was over—provides a fitting coda to the story. Though the chest “barely covered the corner of an oblong table in a Santa Fe conference room,” per Chasing the Thrill, “this treasure mattered. It meant something. … It was Forrest Fenn’s treasure, and in that sense it wildly exceeded my expectations.”

Espionage and Enslavement in the Revolution: The True Story of Robert Townsend and Elizabeth by Claire Bellerjeau and Tiffany Yecke Brooks

In May 1779, a woman named Liss escaped from her enslavers, the Townsend family of Long Island, with the help of a British colonel and ardent abolitionist who probably hid her in one of his regiment’s caravans. Eight days after Liss’ disappearance, Robert Townsend, third son of family patriarch Samuel, penned a letter to his father expressing doubts about the likelihood of her return: “I think there is no probability of your getting her again,” he wrote, “[and I] believe you may reckon her amongst your other dead losses.”

Much about Liss’ life—and her relationship with Robert, whose secret identity as a member of the American Culper Spy Ring only came to light a century after his death in 1838—remains unknown. But as Claire Bellerjeau, historian and director of education at the Raynham Hall Museum, and author Tiffany Yecke Brooks write in their new book, Robert’s eagerness to discourage his father from pursuing Liss may have masked an ulterior motive: namely, embedding the enslaved woman as a mole in a British officer’s household.

Evidence for the authors’ theory is admittedly scant. Records kept by Robert indicate that he purchased items for Liss in the spring of 1782 and may have kept in contact with her in the years following her escape. Toward the end of the war, Bellerjeau tells Newsday, Liss approached Robert and essentially said, “Repurchase me. I don’t want to be evacuated with the British.” He complied, even going so far as to give his father, who was still technically Liss’ owner, £70 for her. She moved into Robert’s household and gave birth to a son who may have been fathered by him in February 1783.

One month after Liss’ arrival on his doorstep, Robert delivered his final piece of wartime intelligence. This timing could have been more than simply a coincidence: “[Liss’] appearance ... now, in the final days of New York’s British rule, may have been an act of both tremendous bravery and self-preservation if she was afraid of being unmasked as an American agent,” according to the book.

Based on years of archival research by Bellerjeau, Espionage and Enslavement takes a hard look at Robert, who became a member of the abolitionist movement but continued to enslave and sell people, while elevating the stories of Liss and others enslaved by the Townsends. “I’m looking to … get the idea into people’s heads that people like Elizabeth can be Founding Fathers and Mothers,” Bellerjeau tells Newsday. “That our story of America can have as a primary figure a person who lived a life like hers.”

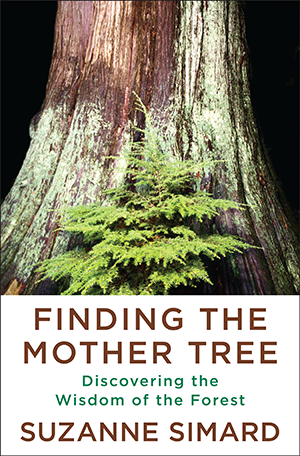

Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest by Suzanne Simard

Subterranean networks of plant roots and fungi lurk beneath the floor of every forest, linking trees and allowing them to communicate chemically, writes Suzanne Simard, a forest ecologist at the University of British Columbia, in her groundbreaking debut book. Blending memoir and scientific research, Finding the Mother Tree “convincingly argues [that trees] perceive, respond, connect and converse,” per Kirkus.

As Simard explains in the book’s introduction, the oldest, largest trees—described by the scholar as Mother Trees, or “majestic hubs at the center of forest communication, protection and sentience”—share resources with younger ones, passing down nutrients, water and even knowledge in a manner not unlike humans taking care of their children. Far from simply competing with each other, as scientists have long theorized, Simard’s research shows that trees cooperate, engaging in interdependent “yin and yang” relationships, as she explained in a 2016 TED Talk.

When Simard first published her findings in 1997, she was met with a wave of criticism, much of which came from older, male scientists who objected to the suggestion that trees might experience emotions and spiritual connections. Though studies conducted in the decades since have confirmed Simard’s increasingly mainstream theories, doubters remain.

Despite facing intense pushback, the ecologist is optimistic about her research’s implications for more effective forest management. “With each new revelation, I am more deeply embedded in the forest. The scientific evidence is impossible to ignore: [T]he forest is wired for wisdom, sentience, and healing,” she writes in Finding the Mother Tree. “This is not a book about how we can save the trees. This is a book about how the trees might save us.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)