After Pearl Harbor, Vandals Cut Down Four of DC’s Japanese Cherry Trees

In response to calls to destroy all the trees, officials rebranded them as “Oriental” rather than “Japanese”

:focal(1870x1485:1871x1486)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/a6/fba6daa3-2df5-49fb-832b-a90e3956aa19/ap080603020399_1.jpg)

This is part of a series called Vintage Headlines, an examination of notable news from years past.

In December 1941, American newspapers were understandably occupied covering a major news story: the country's entry into World War II.

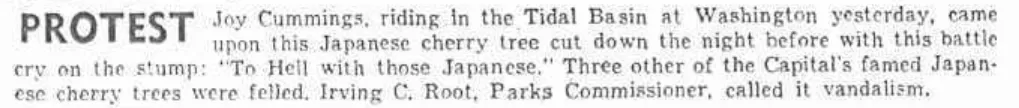

But on December 11, a number of papers—including Yonkers' The Herald Statesman—carried an intruiging item, along with a black-and-white photo, that described a reaction to Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor that's now largely forgotten:

The vandals were never identified, but the carving on the stump made their intent pretty clear: to retaliate against Japan by attacking four of the cherry trees originally donated by the county in 1912 as a gesture of goodwill.

But for many people, destroying just four of the trees wasn't enough. Afterward, according to the Richmond Afro American, there was "talk of cutting [all] the trees down and replacing them with an American variety." In 1942, the Tuscaloosa News reported that "letters are pouring into the National Capital Parks commission, demanding that the gifts from Nippon be torn up by the roots, chopped down, burned."

Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed. 62 years before "Freedom Fries," parks staff decided that a simple change in nomenclature would suffice. Throughout the rest of the war, instead of calling them Japanese cherry trees, they were officially referred to as "Oriental Cherry Trees"—a label apparently presumed to be less inflammatory, partly because China and other Asian countries served as allies during the war.

Still, for the next six years, the National Cherry Blossom Festival—an annual springtime celebration that had been held every year since 1935—was suspended, partly because of wartime austerity, and partly due to the fact that the trees clearly represented the enemy in a brutal and destructive war, regardless of their name.

In 1945, the Victoria Advocate described how before the war, "hundreds of thousands of Americans came to Washington annually to see the pretty flowers." After the Pearl Harbor attack, though, it wrote, "the trees are as colorful as ever, but somehow the citizens don't get the same thrill out of 'em. There's something wrong. You're doggone right there is. It's been wrong since December 7, 1941."

Eventually, though, after the war ended in 1945, anti-Japanese sentiments gradually subsided. The festival was brought back in 1947, and the trees were again allowed to be called "Japanese."

In 1952, in fact, when parks officials became aware that the cherry tree grove that grew along the banks of the Arakawa River, near Tokyo—the grove that had served as the parent stock for the original 3000 saplings donated to Washington in 1912—was ailing due to neglect during the war years, they wanted to help. In response, the National Park Service sent cuttings from its own stock back to Japan to help replenish the site.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)