Why an Alabama Town Has a Monument Honoring the Most Destructive Pest in American History

The boll weevil decimated the South’s cotton industry, but the city of Enterprise found prosperity instead

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/94/5594e452-e804-43d8-b75d-b753861d8138/1024px-boll_weevil_monument_alabama_historical_marker.jpg)

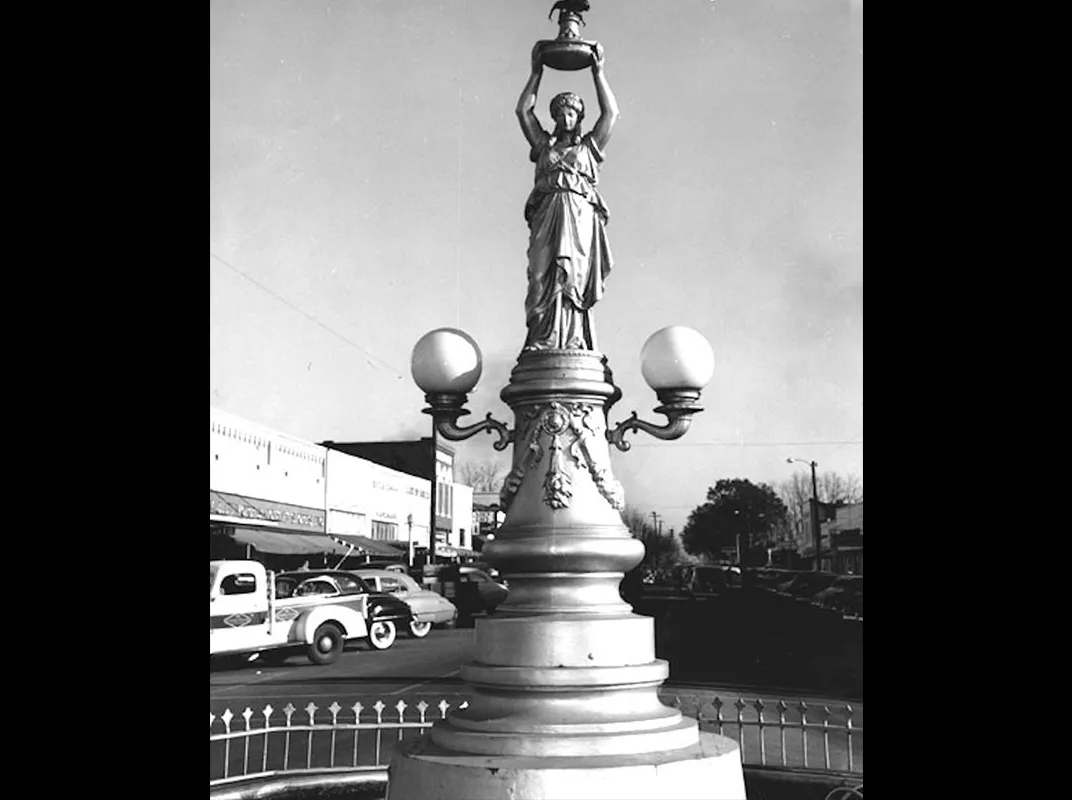

A statue of a Greek woman stands proud in the center of Enterprise, Alabama. Its white marble arms stretch high above its head. Braced in the beautiful woman’s hands is a round bowl, atop which is perched … an enormous bug. It’s a boll weevil, to be precise—about 50 pounds in statue form, but normally smaller than a pinkie fingernail.

Enterprise’s weevil statue dates back to 1919, when a local merchant commissioned the marbled figure from an Italian sculptor. Originally, the classical statue held a fountain above her head; the insect wasn’t added for another 30 years. The plaque in front of it reads the same today as it did then: “In profound appreciation of the boll weevil and what it has done as the herald of prosperity, this monument was erected by the citizens of Enterprise, Coffee County, Alabama.”

The monument could be just another piece of quirky Americana, a town honoring a small aspect of its heritage in a unique way. But the impact the boll weevil has had across the United States is anything but small—and is far from positive. Since its arrival from Mexico in 1892, the weevil has cost the American cotton industry more than $23 billion in losses and prompted the largest eradication effort in the nation's history.

“I cannot think of another insect that’s displaced so many people, changed the economy of rural America, and was so environmentally injurious that everybody clearly rallied around and said we have to get rid of it,” says Dominic Reisig, a professor of entomology at North Carolina State University.

The havoc the boll weevil wrought on the Southern economy was so disruptive that some scholars argue it was one of the factors that spurred the Great Migration—the movement of 6 million African-Americans from the South to urban areas in the North. As the weevil destroyed cotton farms, many farmworkers moved elsewhere for employment, including urban centers.

So why would any town want to honor such a pest with an expensive statue, let alone call it a herald of prosperity? To understand that requires jumping back over 100 years in history, to when the insect first invaded American farmland.

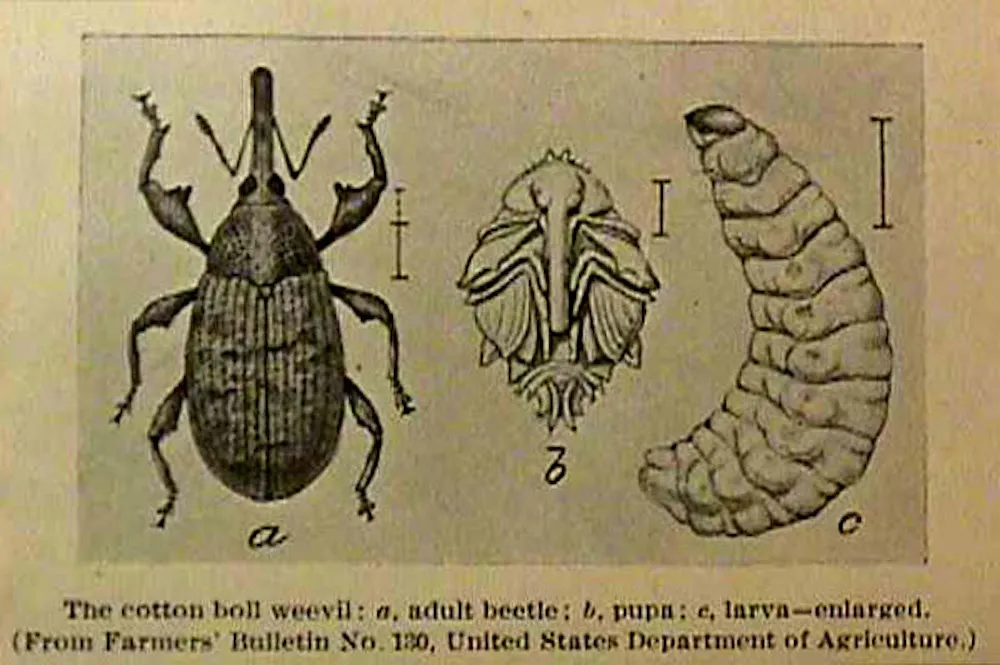

The boll weevil, Anthonomus grandis, is native to Mexico and lives almost exclusively on cotton plants. In the early season, adults feed on cotton leaves and then puncture the cotton “square”—the pre-floral bud of the plant—to lay their eggs. When the eggs hatch, the grubs chew their way through everything inside, and by the time the plants open up, the cotton lint that should be present is largely gone. In a single season, one mating pair can produce 2 million offspring.

The weevil was first spotted in the United in Texas, though no one knows exactly how it came across the border. Although the bugs can only fly short distances, they spread rapidly and their path of destruction had immediate effects. “Within 5 years of contact, total cotton production declined by about 50 percent,” write economists Fabian Lange, Alan Olmsted and Paul W. Rhode. As local economies were devastated, land values plummeted. In 1903, the USDA chief in the Bureau of Plant Industry referred to the pest as a “wave of evil.”

By the 1920s, weevils blanketed the cotton-producing South. They survived from one year to the next by hibernating in nearby woods, Spanish moss and field trash. Farmers couldn’t afford to abandon cotton, especially as scarcity drove up prices further. So they simply grew more cotton—and spent more and more trying to drive away the bugs. As cotton boomed, so did the weevil.

Farmers tried everything to get rid of the weevils: they planted early-maturing varieties of cotton in hopes that they could increase yields before the weevils got to them, experimented with arsenic sprays and powders, and burned their cotton stalks after harvesting. Theodore Roosevelt suggested importing a predatory ant from Guatemala to feed on the weevil. At one point, one-third of all pesticides used in the entire U.S. were targeted at killing boll weevils, Reisig says.

But the boll weevil’s story was different in Enterprise. By 1909, the weevil had reached nearby Mobile County, Alabama. Like elsewhere, cotton was the main cash crop, and with the weevils now in their fields, farmers were getting smaller and smaller yields.

“The Enterprise cotton gin ginned only 5,000 bales [in 1915] compared to 15,000 the year before,” says Doug Bradley, president of the Pea River Historical and Genealogical Society. H.M. Sessions, a man who lived in town and acted as a seed broker to farmers in need, saw the devastation and knew he needed to act.

Farmers could switch to other crops that wouldn’t support the boll weevil, but cotton generated the highest profits and grew on marginal land—“sandy, well-drained land that not a lot of crops can tolerate,” Reisig explains. One of the few crops that could tolerate those conditions: peanuts. After visiting North Carolina and Virginia, where he saw peanuts being grown, Sessions came back with peanut seeds and sold them to area farmer C. W. Baston.

“In 1916, Mr. Baston planted his entire crop in peanuts. That year, he earned $8,000 from his new crop, and paid off his prior years of debt and still had money left over,” Bradley says. At the same time, Coffee County cotton production was down to only 1,500 bales.

Word of Baston’s success spread quickly. Farmers who had once scorned the idea of growing anything other than cotton jumped on the peanut train, and by 1917 regional farmers produced over 1 million bushels of peanuts that sold for more than $5 million, Bradley says.

By 1919—right when the boll weevil scourge was reaching its peak elsewhere in the South—Coffee County was the largest producer of peanuts in the country, and shortly thereafter became the first in the region to produce peanut oil.

Bradley, who worked in the cotton fields as a young boy in the ’40s and ’50s, remembers seeing the weevils and witnessing the havoc they wreaked. But by that point, Enterprise had diversified its crops. In addition to peanuts and cotton, there were potatoes, sugar cane, sorghum and tobacco. It was really thanks to the boll weevil that Coffee County diversified at all, which is why Enterprise erected a statue in its honor.

As for the rest of the South, efforts to combat the weevil continued throughout the 20th century. In 1958 the National Cotton Council of America agreed on farming legislation that would fund research into cotton growing and the boll weevil. Researchers with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service tried the sterile insect technique (filling the environment with sterile mates), which was unsuccessful, and tested a number of pesticides. But neither tactic brought the weevil down—instead, their own pheromones came to be their undoing.

“Scientists realized [pheromones] were chemicals produced by the glands in insects and they changed insect behavior,” Reisig says. “A particular synthetic blend was developed specifically for the boll weevil.” The pheromones lured boll weevils into traps where they could be sprayed with pesticides. That combination drove a 99 percent success rate. Today, the weevil has been eradicated from 98 percent of U.S. cotton land across 15 Southern states and parts of northern Mexico.

For Reisig, it’s a story of beating enormous odds. “It was a really special time and place when everything lined up right. We had political unanimity. The government was willing to give money on the federal and state level. The long-lasting legacy was cooperation among scientists and the development of things like pheromones, and investment in institutions like the USDA.”

For Bradley and the town of Enterprise, the lesson is a bit subtler. “So many people think, why did you build a statue to honor something that did so much destruction?” Bradley says. “It was more to recognize the fact that the boll weevil caused farmers to seek a better cash crop to replace cotton.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)