Airmail Letter

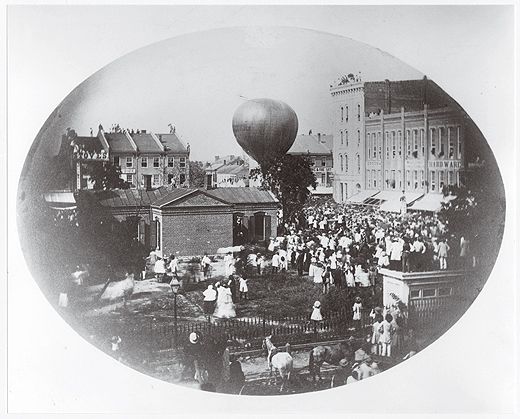

Stale Mail: The nation’s first hot-air balloon postal deliveries barely got off the ground

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/object_aug06_388.jpg)

If you happened to be a child in the New York City of 1859, awaiting a birthday letter from, say, Aunt Isabel in Lafayette, Indiana—containing, perhaps, a shiny silver dollar—you were going to be disappointed. The mail that your aunt had expected to be unusually timely was going to be late. And what earns this delayed delivery a place in the annals of postal irony is that the letter you were anticipating was aboard America's first airmail flight.

More accurately, we should call the delivery lighter-than-air mail, since this imagined letter would have been one of 123 handed over to John Wise, aeronaut and pilot of the balloon Jupiter.

The postmaster of Lafayette had entrusted the 51-year-old Wise, a former builder of pianos, with a locked bag containing letters and a few circulars. Although Lafayette lay in the path of the prevailing westerlies, in the 90-degree heat of August 17, the air was still. Wise had to ascend to 14,000 feet—an astonishing altitude at the time—before he found any wind at all.

The wind was light, however, and carried Jupiter south, not east. After more than five hours aloft and with only 30 miles traveled, Wise had to descend near the town of Crawfordsville, Indiana. The Lafayette Daily Courier wryly dubbed the flight "trans-county-nental." After landing, Wise gave the bag of mail to a railroad postal agent, who put it on a New York-bound train.

The high hopes for this newfangled idea still resonate in the one piece of mail known to exist from that day's attempt. Today held in the collections of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, in Washington, D.C., the letter was sent in an ornately embossed envelope, bearing a three-cent stamp, to one W H Munn, No. 24 West 26 St., N York City. To the left of the address are written the words "Via Balloon Jupiter, 1858." According to Ted Wilson, registrar of the Postal Museum, the post office required this phrase in order to place letters aboard the balloon. That the date is a year too early, and the handwriting appears different from that of the address, lend an aura of mystery.

Wilson notes that the museum purchased the letter in 1964 from a stamp dealer, adding that "It had only come to light a few years earlier." This rare find, consisting of a single page written in sepia-colored ink and signed by Mary A. Wells, is devoted mainly to the method of delivery: "Dear Sir, Thinking you would be pleased to hear of my improved health I embrace the opportunity of sending you a line in this new and novel way of sending letters in a balloon."

Wise's pluck exceeded his luck. A few weeks before his shortfall delivery of New York mail, he had made another attempt, taking off in a different balloon from St. Louis for New York City. On that flight, Wise covered 809 miles, the longest balloon journey ever made at the time, but a storm caused him to crash in Henderson, New York. Since the mail he was carrying was lost in the crash, his 30-mile August flight is the one counted as history's first airmail.

Despite the unpredictability and danger, Wise never lost his enthusiasm for balloon flight, or his belief that it was the wave of the future. During the Civil War, he flew observation balloons for the Union Army. Twenty years after his Lafayette takeoff, at the age of 71, he died in a crash into Lake Michigan.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)