An American Who Died Fighting for Indonesia’s Freedom

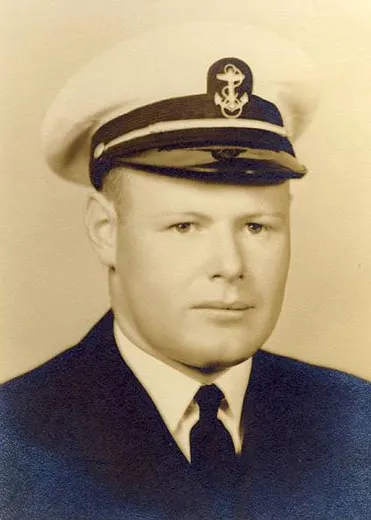

Bobby Freeberg, a 27-year-old pilot from Kansas, disappeared while flying a supply-filled cargo plane over the Indonesian jungle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Java-Island-Indonesia-631.jpg)

On the morning of September 29, 1948, a Douglas DC-3 cargo plane took off from Jogjakarta on the island of Java. Aboard the flight were five crewmen, one passenger, medical supplies and 20 kilograms of gold. Registered as RI002, the plane was the backbone of Indonesia’s fledgling air force in its independence movement, which was fighting for survival against the Netherlands’ colonial army. Within a year, the Dutch would be forced to hand over power to the Republic of Indonesia, ending a four-year war of liberation in the wake of Japan’s defeat in 1945 (Japan had invaded and occupied Indonesia during World War II).

But the six men aboard RI002, including its captain, Bobby Freeberg, a blond-haired, blue-eyed 27-year-old from Parsons, Kansas, never saw this victory. Sometime after the plane took off from the town of Tanjung Karang on the southern tip of Sumatra, it disappeared. Thirty years later, two farmers found part of its wreckage in a remote jungle, along with scattered human remains. Indonesia promptly declared the five fallen countrymen to be heroes who had died in the course of duty.

For Freeberg, a highly decorated Navy pilot, the wait for recognition has taken even longer. Last May, he was honored in an exhibition at Indonesia’s National Archives in the capital of Jakarta, along with Petit Muharto, his former co-pilot and friend, who missed the final flight. Freeberg is now recognized as an American who helped Indonesia win its independence. “He’s a common national hero,” insists Tamalia Alisjahbana, the show’s curator and director of Indonesia’s National Archives Building.

However, this flurry of interest is bittersweet for Freeberg’s family, who still wrestle with his dramatic disappearance. His niece, Marsha Freeberg Bickham, believes that her uncle didn’t die in a plane crash but was instead captured and imprisoned by the Dutch, and later died in captivity.

According to Bickham, not long after RI002 vanished, Kansas Senator Clyde Reed, a family friend from Parsons, told Freeberg’s parents that their son was alive and that he was trying to get him released from prison. But that was the last the Freeberg family would hear, as Senator Reed died of pneumonia in 1949.

Freeberg was well known to authorities as an American pilot working for the Indonesians, but Dutch archives show no record of his capture, explains William Tuchrello, the Library of Congress attaché in Jakarta, who helped research the exhibition. Tuchrello is mystified as to why there might have been a coverup of what happened to Freeberg’s plane. “We asked the Dutch, ‘Is there anything in your files that would verify any of this?’” he says. None has turned up. For her part, Alisjahbana has asked a Dutch historian to submit the case to a TV show in the Netherlands in which experts try to solve mysteries from the past. One person who never gave up hope of tracing “Fearless Freeberg,” as his Navy buddies called him, was Muharto, his Indonesian co-pilot. He kept in touch with Freeberg’s family until his death in 2000. “Bobby lit a light in him. When I met him 40 years later, it was still lit,” says Alisjahbana.

Born into a privileged Javanese family, Muharto was a medical student in Batavia, as Jakarta was then called, when Japan invaded in 1942. When the independence struggle broke out he decided to join the air force. The problem was that Indonesia had neither aircraft nor pilots. So Muharto was sent to Singapore and Manila to find commercial airlines willing to defy a Dutch blockade on the rebels. Without an air bridge to bring in arms and medicines and fly out spices and gold, the revolution was sunk.

One pilot willing to take a chance was Freeberg, who had left the Navy in 1946 and failed to find a civil aviation job back home. Back in the Philippines, he began flying for CALI, an airline in Manila, and saved up enough to buy his own DC-3. Later that year, he began flying exclusively for the Republic of Indonesia, which designated his plane as RI002. He was told that RI001 was reserved for the future plane of Indonesia’s first president after independence. Indeed, the 20 kilograms of gold carried on RI002’s final flight – and never recovered – was intended to be used to purchase more aircraft.

Freeberg was a mercenary, flying missions for a foreign power. He was planning to save money and return to America; he was engaged to a nurse he’d met in Manila. Indonesians called him “Bob the Brave.” But his work also began to exert an emotional pull on him and make him identify with a political cause. He wrote to his family of the injustice suffered by Indonesians at the hands of the Dutch and the resilience of ordinary people. “It is pretty wonderful to see a people believe in the freedom that we Americans enjoy (and) ready to fight for the achievement of this view,” he wrote.

Bickham says that Freeberg went to Indonesia because he loved to fly and stayed because he admired Indonesia’s cause. His disappearance was devastating to the family, she says, all the more so because of the lack of a body and some mistrust of the U.S. government, which initially sided with the Netherlands in the conflict before swinging behind the fledgling Indonesian republic. Insurers refused to pay out on Freeberg’s missing plane. His fiancée, a Naval nurse from Deposit, New York, died last year without ever marrying. “Her niece told me that she asked for Bobby on her death bed,” Bickham writes in an email.

Curator Alisjahbana had heard about Freeberg, who was dubbed the “One Man Indonesian Air Force” by the media. In June 2006, she hosted Donald Rumsfeld, then U.S. Defense Secretary and a former Navy pilot, at her museum during an official visit. Knowing that Rumsfeld was a military history buff, she told him the story and asked him to send her Freeberg’s wartime records. That got the ball rolling for last year’s exhibition, entitled “RI002: Trace of a Friendship.” The catalog leaves open the question of what happened to Freeberg after the plane went missing in 1948.

Meanwhile, Bickham, 57, who was born in Parsons and lives in Half Moon Bay, California, was feeling her own way through family lore about Freeberg. Her father, Paul, was the youngest of three brothers, who all served in World War Two (Paul was in Europe). The family spoke rarely of Bobby, says Bickham, as they felt so traumatized by their loss. “They spent so much money and went through so much without getting any answers,” she says.

Bickham was always curious about her uncle’s mysterious disappearance. But it wasn’t until 2008, when the U.S. Embassy contacted the family, that she was drawn into the search. Before her father died in January 2009, he gave Bickham around 200 of Freeberg’s letters and told her to find out what she could of his fate. That hunt is still on.