Ancient Greeks Voted to Kick Politicians Out of Athens if Enough People Didn’t Like Them

Ballots that date more than two millennia old tell the story of ostracism

:focal(792x472:793x473)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/f9/22f9ec45-461d-4135-aa63-27efe5721e6d/ancient_greece2.jpg)

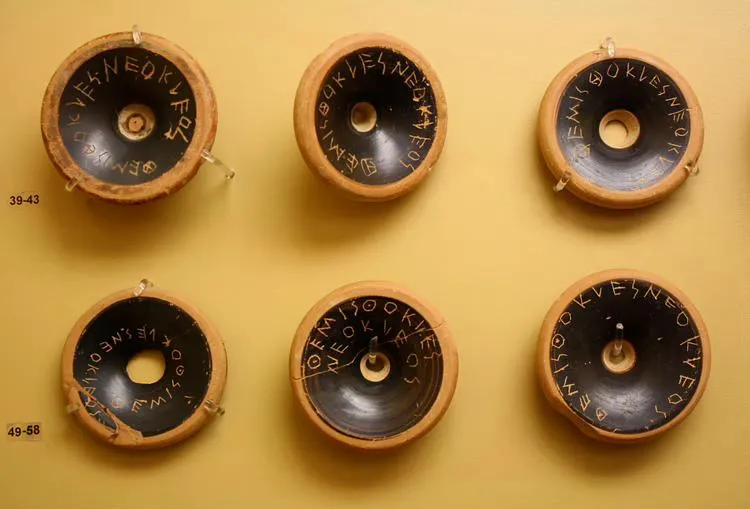

In the 1960s, archaeologists made a remarkable discovery in the history of elections: they found a heap of about 8,500 ballots, likely from a vote tallied in 471 B.C., in a landfill in Athens. These intentionally broken pieces of pottery were the ancient equivalent of scraps of paper, but rather than being used to usher someone into office, they were used to give fellow citizens the boot. Called ostraca, each shard was scrawled with the name of a candidate the voter wanted to see exiled from the city for the next 10 years.

From about 487 to 416 B.C., ostracism was a process by which Athenian citizens could banish someone without a trial. “It was a negative popularity contest,” says historian James Sickinger of Florida State University. “We're told it originated as a way to get rid of potential tyrants. From early times, it seems to be used against individuals who were maybe not guilty of a criminal offense, so [a case] couldn't be brought to court, but who had in some other way violated or transgressed against community norms and posed a threat to civic order.” Athenians would first take a vote on whether there should be an ostracophoria, or an election to ostracize. If yes, then they would set a date for the event. A candidate had to have at least 6,000 votes cast against him to be ostracized and historical records suggest that this occurred at least a dozen times.

Ostracisms occurred during the heyday of Athenian democracy, which allowed direct participation in governance for the city-state's citizenry, a population that excluded women, enslaved workers and foreign-born residents. Though the number of citizens could sometimes be as high as 60,000, a much smaller group of men was actively involved in Athenian politics. Ostracism could be a guard against any one of them gaining too much power and influence. Nearly all of Athens' most prominent politicians were targets. Even Pericles, the great statesman and orator, was once a candidate, though never successfully ostracized; his ambitious building program that left us the Parthenon and the other monuments of the Acropolis as we know it today was not universally beloved.

Written ballots were fairly unusual in Athenian democracy, Sickinger says. Candidates for many official positions were chosen by lot. During assemblies where citizens voted on laws, the yeas and nays were typically counted by a show of hands. Ostraca, then, are the rare artifacts of actual democratic procedures. They can reveal hidden bits of history that were omitted by ancient chroniclers and offer insight into voter behavior and preferences that would otherwise be lost.

The first ostracon was identified in 1853, and over the next century, only about 1,600 were counted from various deposits in Athens, including some from the Athenian Agora, or marketplace, which Sickinger has been studying. So it was a remarkable haul when a German team of archaeologists started finding thousands of ostraca in the Kerameikos neighborhood of Athens in 1966. The Kerameikos was just northwest of the ancient city walls and famous for its pottery workshops where artists created Attic vases with their distinctive black and red figures. These ballots—which had been made from fragments of a variety of types of household vases and even roof tiles and ceramic lamps—had been dumped along with heaps of other trash to fill in an abandoned channel of the Eridanos river. Excavations continued there until 1969, and some of the ostraca were studied over the next few decades, but it wasn’t until 2018 that Stefan Brenne of Germany’s University of Giessen published a full catalogue describing all 9,000 ostraca that were excavated in the Kerameikos between 1910 and 2005.

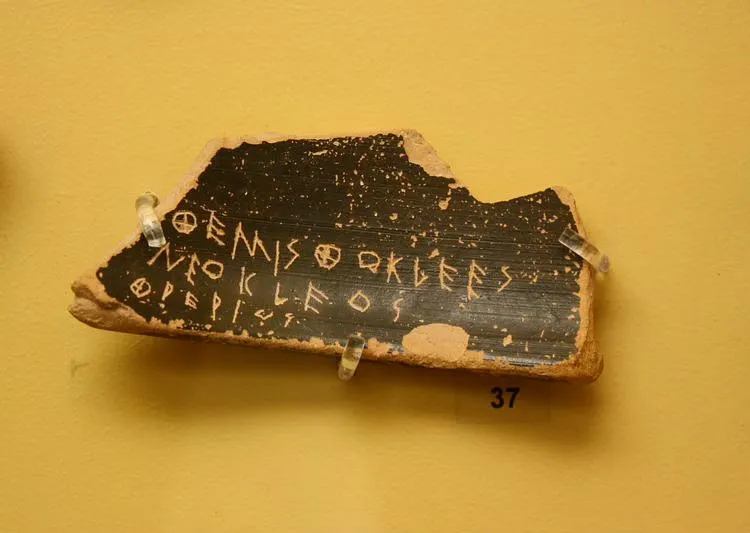

From this collection of ostraca, the most votes were cast against Athenian statesman Megakles, who was apparently hated by many for his ostentatious and luxurious lifestyle. Historical records indicate that Megakles had been ostracized in 486 B.C., but that date didn’t seem to fit with the archaeological evidence: Other ballots found in the Kerameikos hoard contained names of men who didn’t begin their political careers until the 470s B.C. and some ostraca matched with later styles of pottery. Those clues led archaeologists to conclude that Megakles returned to Athens and was ostracized again in 471 B.C. The other top candidate that year appeared to be Themistocles, the populist general who fought in the Battle of Marathon. He was ostracized the next year.

The votes often concentrated around just two or three people, but other individuals—some of whom scholars never knew existed—also received votes in fairly large numbers according to ostraca deposits studied by archaeologists, Sickinger says. “Writers from antiquity focus on just a few big men," he adds. "History was the history of leading figures, powerful individuals, generals and politicians, but others were maybe not quite as prominent, but clearly prominent enough that dozens or hundreds of individuals thought them worthy of being ostracized."

Besides the names of forgotten Athenian men, the ostraca themselves also reveal Athenians’ attitudes toward their fellow citizenry. Some feature nasty epithets: “Leagros Glaukonos, slanderer;” “Callixenus the traitor;” “Xanthippus, Ariphron's son, is declared by this ostracon to be the out-and-out winner among accursed sinners.” Others took jabs at the personal lives of the candidates. One ballot, cast in 471 B.C., was against “Megakles Hippokratous, adulter.” (Adultery was then a prosecutable offense but also may have been used as a political attack.) Another declared “Kimon Miltiadou, take Elpinike and go!” Brenne explains that a noble-born war hero (Kimon) was suspected of having an incestuous relationship with his half-sister (Elpinike.) The mention of her name is one of the few instances where a woman’s name appears on an ostracon.

According to Brenne, some of these comments may reflect personal grievances against candidates, but the time leading up to an ostracophoria, political campaigns against candidates were probably rampant. As he once wrote, “most of the remarks on ostraca belong to low-level slogans easily propagated,” reminiscent of tabloid coverage of candidates today. Meanwhile, researchers have uncovered a few examples of Athenians casting their vote not against a fellow citizen but limós, or famine. Sickinger says it's unclear whether this was meant to be a sarcastic or sincere gesture, but some Greek cities had rituals where they would drive out a scapegoat (usually an enslaved worker) designated to represent hunger.

The extraneous remarks on ostraca, alongside other irregularities like misspellings and crossed-out letters, indicate that no strict format for the ballots had been established. It seems that voters didn’t even have to write on their own ballots. Scholars have found several examples of ostraca that fit together, as if broken from an old pot on site, with matching handwriting as well, suggesting some Athenians helped their friends and neighbors write down their vote. Archaeologists have also found a trove of seemingly unused but mass-produced ballots against the general Themistocles in a well on the north slope of the Athenian Acropolis.

“The assumption is that they did not have restrictions on someone else producing your vote for you,” Sickinger says. But he adds that it seems likely that voters filed into the marketplace through specific entrances, according to their tribes, so some oversight or supervision guarded against fraud in ballot casting.

The ancient writer Plutarch tells us that the final ostracism took place in 416 B.C. when political rivals Alcibiades and Nicias, realizing they were both facing ostracism, teamed up to turn the votes of their fellow citizens against another candidate, Hyperbolus, who was banished. The outcome apparently disgusted enough Athenians that the practice ended.

“I try to convey to my students that when we talk about the Athenians as inventing democracy, we tend to put them on a pedestal,” Sickinger says. “But they were victims of many of the same weaknesses of human nature that we suffer from from today. [Ostracism] wasn't necessarily a pristine, idealistic mechanism, but it could be abused for partisan ends as well.”