Ancient Rome’s Forgotten Paradise

Stabiae’s seaside villas will soon be resurrected in one of the largest archaeological projects in Europe since World War II

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/stabiae_Stabiae2.jpg)

It was Malibu, New York and Washington, D.C. all rolled into one. Before A.D. 79, when the erupting Mount Vesuvius engulfed it along with Pompeii and Herculaneum, the small port town of Stabiae in southern Italy was the summer resort of choice for some of the Roman Empire's most powerful men. Julius Caesar, the emperors Augustus and Tiberius and the statesman-philosopher Cicero all had homes there.

And what homes they were. Looking out over the Bay of Naples, enjoying fresh breezes and the mineral-rich water from natural springs, the seaside villas ranged in size from 110,000 to 200,000 square feet and represented the best in painting, architecture and refinement—apt testimonials to their owners' importance.

With those glory days long gone, finding the site of the ancient resort and its opulent villas today is like going on a treasure hunt. Arriving in Castellammare di Stabia, the bustling, working-class town of 67,000 on the road to Sorrento that is its modern replacement, there is no hint of its predecessor's eminence. Not much point asking the locals, either: many of them ignore Stabiae's existence, let alone its location. A 20-minute walk gets you to the general area, but it's still hard to figure out exactly how to get to the villas.

That's destined to change. Stabiae is about to be wrested from anonymity, thanks in no small measure to a local high school principal and one of his students. Large-scale excavations are scheduled to begin this summer on a $200-million project for a 150-acre Stabiae archeological park—one of the largest archeological projects in Europe since World War II.

Thomas Noble Howe, Coordinator General of the non-profit Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation (RAS) and art history chair at Southwestern University in Texas, describes the villas, believed to number at least six or seven, as "the largest concentration of well-preserved elite seafront Roman villas in the entire Mediterranean world."

"These villas were not just places of retreat and luxury for the Roman super-wealthy," says the foundation's U.S. Executive Coordinator Leo Varone, an architect born in Castellammare whose vision is behind the project. "In the summer months, the capital virtually moved from Rome to here, and some of the most pivotal events of the Roman Empire actually occurred in the great villas of the Bay of Naples."

Linked to an urban renewal plan for Castellammare, the park will be easily accessible from that town and from Pompeii (three miles away) via the existing Circumvesuviana commuter train line linked to a new funicular railway. The park's amenities will include panoramic pedestrian walkways, an outdoor theater, a museum, restaurant and visitor and educational centers, with each phase opening as it is completed. To protect the integrity of the area, a maximum of 250,000 tourists will be allowed each year—far fewer than the 2.5 million who visit Pompeii.

The uncovering of the original, street-level entrance quarters of Villa San Marco, one of two well-excavated villas, will be the first major excavations done in Stabiae in over half a century and the latest chapter in a story both long and poignant. After some initial digging in the 18th century, work was stopped so that more money could be funneled toward excavating Pompeii. The villas that had been exposed were reburied—so well, in fact, that by the mid-20th century they were long lost and their location forgotten.

That's when Libero D'Orsi, the principal of the local high school that Varone attended, used his own funds to look for the villas with the help of the school janitor and an unemployed mechanic. They found them but eventually ran out of money and suspended their work.

Inspired by his high school principal and the various archaeological sites surrounding Stabiae, Varone had no doubt about his career choice. "Since I was seven years old," he says, "I wanted to be an architect." After getting a degree from the University of Naples, he went to the University of Maryland and for his master's thesis offered a design that would resurrect the archeological site, while also improving the economy of his hometown.

That was the genesis of RAS and the creation of an ambitious project that has partnered the university with the Archeological Superintendency of Pompeii, which has authority over Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae. The foundation has also enlisted national and international partners and funding from donors in the United States, Italy and Campania.

A visit to Villa San Marco explains all this support—it's like a window into the world of Rome's titans. Plenty of open space for the groupies and "clients" who followed or lobbied the great men; cold, tepid and hot spas; a gym; a kitchen big enough to feed 125 people; lodging for 100 servants; a room for sacrificial offerings; hidden gardens; tree-line walkways; and a pool-facing living rooms (dietae) and panoramic dining rooms (oecus)—said to have been the place for the ultimate power lunches.

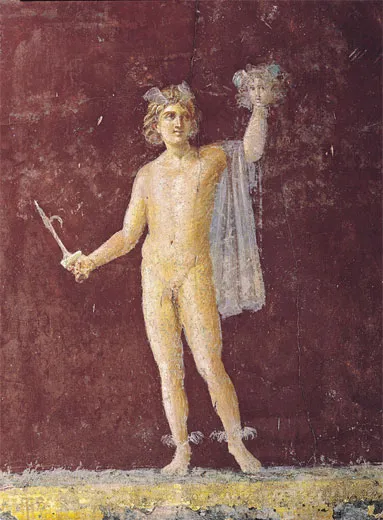

Frescoes were everywhere, including the rooms thought to have belonged to the kitchen staff—an indication of the importance that this area attached then as now to food preparation. Some of the works, still vibrant after all these years, are being restored under the RAS Adopt-A-Fresco Campaign that allows individuals or groups to pay for their repair. The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg will showcase some of these restored wall paintings in September.

In order to engage the best scientific minds, RAS recently opened the first residential and academic facility for visiting scholars in Southern Italy, the Vesuvian Institute for Archaeology and the Humanities.

The influence of modern technology is already having an effect. Last year a small exploratory excavation confirmed an earlier study that Villa San Marco has a still-buried 355-foot colonnaded courtyard, which Howe calls "the most significant recent discovery in the Vesuvian region in the last generation." Archaeologists also recently unearthed a skeleton—from the eruption of Vesuvius—in the region for the first time.

Varone says no one knows exactly the geographical boundaries of the resort or precisely the number of villas that are still buried. Likewise, no one knows what other long-buried secrets could be revealed as the story unfolds.