Andrew Jackson Was a Populist Even on His Deathbed

This lavishly decorated crypt was considered too ornate for the American president

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/35/a135315e-4a26-4abc-8c74-377869ac3132/mar2017_b01_nationaltreasureandrewjacksonsarcophagus.jpg)

Andrew Jackson lay gasping in his bed at home in Tennessee, the lead slugs in his body at long last having their intended effect. It was the spring of 1845 and “Old Hickory”—hero of the War of 1812 and the nation’s seventh president, born 250 years ago, on March 15, 1767—was finally dying after so many things and people had failed to kill him. The 78-year-old was wracked by malarial coughs from his field campaigns against the British, Creeks and Seminoles, and plagued by wounds from two duels, which had left bullets lodged in his lungs and arm. It was so apparent he would soon be buried that a friend offered him a coffin.

This was no ordinary box, however. It was a massive and ornate marble sarcophagus. Jackson’s old compatriot Commodore Jesse D. Elliott had purchased it from Beirut while serving as commander of the U.S. naval fleet in the Mediterranean, and brought it back in his flagship the USS Constitution, along with a mummy and a dozen Roman columns. The 71⁄2- by 3-foot sarcophagus, embellished with carved rosettes and cherubs, was thought to have once held the remains of the third-century Roman ruler Alexander Severus. Elliott believed it would be an illustrious vessel for the corpse of the former president. “Containing all that is mortal of the patriot & hero, Andrew Jackson, it will, for a long succession of years, be visited as a hallowed relic,” he predicted.

Elliott’s proposal said much about the powerful personality cult surrounding the president and the fanatical worshipfulness of his admirers. It also said something about the size of Jackson’s ego and taste for tribute that Elliott believed he would accept it.

Jackson’s reputation as a populist was disputed by his contemporaries. To his admirers he was a supremely gifted leader, to his critics, a self-interested tyrant and power-mad chieftain, whose farewell address was “happily the last humbug which the mischievous popularity of this illiterate, violent, vain and iron-willed soldier can impose upon a confiding and credulous people,” wrote one Whig newspaper.

Was Jackson truly, as he called himself, “the immediate representative of the American people”? Or was it “effrontery,” as his alienated vice president, John C. Calhoun, put it, to call himself a champion of the common man?

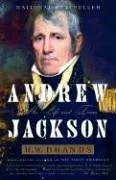

“He certainly believed that he came from the people and exercised power on behalf of the people,” says historian H. W. Brands, author of Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times. “But he wasn’t like most people who voted for him.”

He was the sworn enemy of elitism, who bore scars from a sword wound on his head for refusing to polish a British officer’s boots after being captured as a 14-year-old soldier in South Carolina during the American Revolution. Yet he was a remorseless slaveholder who chased gentleman-planter status. He was a merciless remover of Indians yet a tender collector of orphans, who took in a Creek boy, Lyncoya, found next to the child’s dead mother on a battlefield, as well as several nephews. He was a savage swearer of oaths, “a barbarian who could not write a sentence of grammar and hardly could spell his own name,” according to his rival John Quincy Adams. Yet a surprised hostess once found Jackson to be a courtly “prince” in a parlor.

He had the humblest beginnings of any president up to that point and despised inherited wealth, yet he was a dandy preoccupied with the cut of his coat and the quality of the racehorses at his plantation, the Hermitage. “Infatuated man!” Calhoun railed against him. “Blinded by ambition—intoxicated by flattery and vanity!”

Yet for all that he loved adulation, Jackson declined the sarcophagus. “I cannot consent that my mortal body shall be laid in a repository prepared for an Emperor or a King—my republican feelings and principles forbid it—the simplicity of our system of government forbids it,” he wrote to Elliott.

Jackson died a few weeks later, on June 8, 1845. “I wish to be buried in a plain, unostentatious manner,” he instructed his family. He was placed alongside his wife at the Hermitage, without much in the way of ceremony, but with a huge outpouring from the thousands who attended, including his pet parrot, Pol, who had to be removed for squawking her master’s favorite oaths.

As for Elliott, he gave the empty sarcophagus to the fledgling Smithsonian. “We cannot but honor the sentiments which have ruled his judgement in this case,” Elliott observed of the president, “for they are such as much add to the lustre of his character.”

Editor’s Note, March 22, 2017: This article has been updated to reflect Commodore Jesse D. Elliott’s report that he purchased the sarcophagus in Beirut.