Arthur Radebaugh’s Shiny Happy Future

For five years, a popular comic strip gave us a preview of life in Suburbatopia

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111104100015581004-ctwt-sm-470x251.jpg)

Whenever people discuss retro-futurism the first things that often come to mind are flying cars, jetpacks, meal pills and robot butlers. These were the dreams of a leisurely utopian world that would be built on the most advanced technologies history had ever seen. The promise of these products and the sincere belief in their inevitability flourished in the 1950s. After World War II, Americans were told that we would harness technology to make our lives easier, our products cheaper and our workers more productive. It was a belief in a sort of Technological Manifest Destiny — promoted through advertisements, theme parks and Saturday morning cartoons.

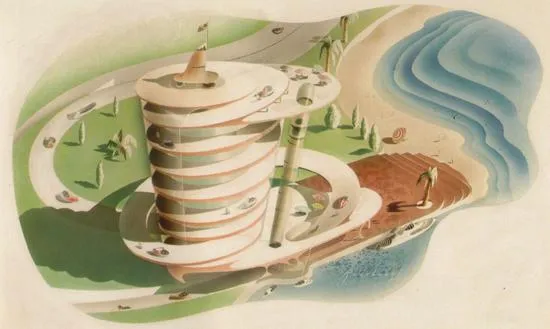

When it comes to the shiny, happy, techno-utopian futures of the 1950s and 60s most people remember Hanna-Barbera’s “The Jetsons” or Walt Disney’s Tomorrowland. But one of the great forgotten techno-utopian artists of the mid-20th century, Arthur Radebaugh, deserves recognition as well for his contributions to the world of futurism. As the illustrator of a late 1950s-early 60s newspaper comic called Closer Than We Think and countless other advertisements and magazine covers, Radebaugh helped shape mid-century American expectations for what the future held.

Arthur Radebaugh (1906-1974) was born in Coldwater, Michigan and would eventually establish his homebase in Detroit—though he spent much of his time in the late 1950s and 60s wandering the country in his Ford Thames, which had been converted to house a mobile art studio. Radebaugh briefly attended the Chicago Art Institute in 1925 but dropped out and spent the late 1920s working as a bus driver, hotel clerk and a theater usher. He moved back to Michigan in the 1930s and worked as a sign painter. He married his wife Nancy in 1934 and began to get illustration work for magazines like Esquire. During World War II Radebaugh designed armored cars and artillery for the Army. After the war, Radebaugh went to Detroit where he was Chief of the Army’s Industrial Design Branch and later went on to work as a designer for companies like Chrysler, Bohn and Coca-Cola.

Radebaugh’s Sunday comic strip Closer Than We Think was syndicated in the United States and Canada and ran for five years. The strip debuted January 12, 1958 with “Satellite Space Station” and ended on January 13, 1963 with a panel about the “Family Computer.” The strip reached about 19 million newspaper readers at its peak and gave people a look at some of the most wonderfully techno-utopian visions that America had to offer. In the May 5, 1958 edition of the strip, Radebaugh looked at the “push-button school” of tomorrow, with computer consoles as every child’s desk. The February 1, 1959 strip imagined the electronic home library of the future, with microfilm projections on the wall. The April 9, 1961 edition of the strip showed the factory farm of tomorrow. And the October 4, 1958 strip predicted jetpack mailmen hopping from house to house in Suburbatopia.

Radebaugh loved experimenting with different mediums, including airbrush and fluorescent paints. The May 2, 1947 Portsmouth Times (Portsmouth, Ohio) ran a piece that looked at the work he was doing in the late 1940s when he was Chief of the Army’s Industrial Design Branch.

Radebaugh, whose studios are in Detroit, Mich., helped design armored cars, bazookas and artillery for the Army. Now, as an outstanding designer of futuristic life, he conceives jet-propelled space ships; heli-cruisers for Sunday drivers; streamlined overhead tramways carrying cars made from surplus Army aircraft fuselages. He paints most of these imaginative themes conventionally, then switches out the regular lights in his studio, turns on a ultra-violet beam, and adds his fluorescent paint. Illuminated by the invisible rays of the ultra-violet light, windows blaze light, stacks belch smoke.

Arthur Radebaugh died in a Veteran’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Michigan on January 17, 1974. At the time of his death, his body of work in magazines and newspapers had been largely forgotten. But through the help of some very dedicated people online, including Tom Z., who has kindly provided many of the Closer Than We Think comic strips I’ve featured on Paleofuture over the years, Radebaugh has hopefully found a new audience to inspire.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)