An Attempt to Keep the Dying Gottschee Culture Very Much Alive

Inspired by a trip to Slovenia with her grandmother, one New Yorker took it upon herself to chronicle the story of a lost piece of European history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/73/2b73af36-45e5-4a9d-9300-c23128d68c76/gotschee.jpg)

It used to be difficult for Bobbi Thomason to explain where her grandmother comes from. Relatives used all sorts of names to describe it: Austria, Yugoslavia, Slovenia, the Hapsburg Empire. “It was really quite confusing to me,” says Bobbi, who stands a few inches taller than her grandmother and squints warmly when she smiles. All those place names were accurate at one time. But the name that lasted longest was Gottschee.

Her grandmother goes by a few names, too: Oma, Grandma, and her full name Helen Meisl. She left Gottschee in 1941, and didn't go back for 63 years.

When she finally did, it was 2004 and she was 74 years old. Her hair had turned white and her husband had died, but she laughed a lot and was close to the women in her family. Helen boarded a plane from New York to Vienna. Then she drove with two daughters and Bobbi to the village where she'd grown up. It was evening, and dark patches of forest flickered past the windows.

When the sun rose over the county of Kočevje, in southern Slovenia, Helen saw that her hometown looked only vaguely familiar. Most of the roads were still made of dirt, but electricity and television had been added since she'd left. The white stucco walls of squat houses had cracked and discolored. Old street signs, once written in German, had been discarded and replaced with Slovene signs.

Helen reached the house that her husband had grown up in. She and Bobbi stood at the threshold but didn't enter, because the floorboards looked too flimsy to support their weight. Holes in the roof let the rain in; holes in the floor showed through to the earth basement. It was comforting to know the building still existed, but sad to see just how modest its existence was.

* * *

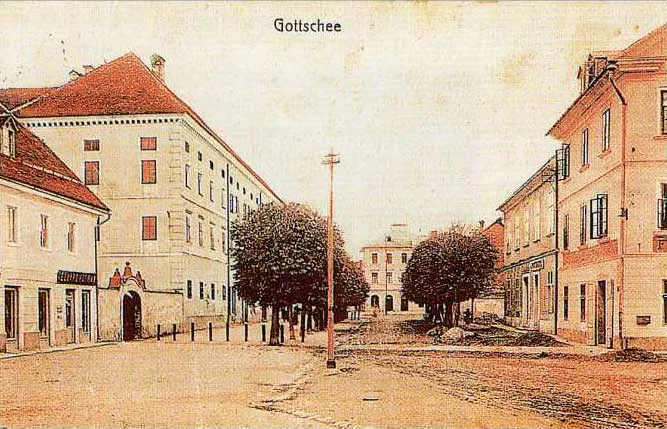

Gottschee was once a settlement of Austrians in what's now Slovenia, which was itself once Yugoslavia. It was called a Deutsche Sprachinsel—a linguistic island of German speakers, surrounded by a sea of Slavic speakers. The Gottscheers arrived in the 1300s, when much of the area was untamed forest. Over the course of 600 years, they developed their own customs and a dialect of Old German called Gottscheerish. The dialect is as old as Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. Germans only vaguely understand it, the way an American would only vaguely understand Middle English.

For centuries, European empires came and went like the tides. But when World War II came, Gottschee abruptly vanished from the map. Today, there are hardly any traces of a German community there. In what remains of Helen's childhood home today, saplings are pushing their way through the floorboards.

“Gottschee will always be my home,” says Helen, who's now 85 and lives in the Berkshires. She and her husband moved later in life, because the green fields and leafy forests of Massachusetts reminded them of their birthplace. “I was born in Gottschee, I will always speak my mother language.”

Only a few hundred people speak the Gottscheerish dialect today, and almost all of them left Gottschee long ago. Yet a proud and thriving community of Gottscheers still exists—in Queens, New York.

In fact, Helen first met her husband in Queens—at Gottscheer Hall, which hosts traditional Austrian meals and choir performances in the Gottscheerish dialect. The hall is an anchor for the community. It's decorated with dozens of portraits of young women who served as “Miss Gottschee,” chosen each year to represent the Gottscheers at events. So complete was the Gottscheer transplantation that by the 1950s, it was possible to meet someone from your birthplace, even at a New York polka dance thousands of miles from home.

The journey back to Kočevje helped Helen accept how much had changed. But for Bobbi, it was more transformative: It helped her understand just how much she didn't know about her roots. During the trip, she heard stories her grandmother had never told before. She started to wonder about her late grandfather, who had been conscripted into the German army at 13 years old, and who had to wander through Austria in search of his family when the war ended in 1945.

Bobbi started to understand just how unlikely her grandparents' migration had been. Family traditions took on new meaning. As a child, she sometimes baked apple strudel with her grandmother. “It requires her pulling out the whole dining room table, to roll the dough,” Bobbi remembers. “The saying is that you should be able to read a newspaper through it.” Her grandfather—a thin, stoic man who liked to read the New York Daily News in a lawn chair—would critique their work when the layers were too thick.

When Bobbi stood in the doorway of her grandfather's childhood home in Kočevje, she wished she could step inside and look around. Peering into the house was a way of peering into the past. A looking glass. Bobbi wanted to know what might be waiting inside, just out of view.

* * *

In 2005, after returning from the trip, Bobbi started contacting Gottscheer organizations in New York. She was considering graduate school in European history and wanted to interview a few older Gottscheers.

To Bobbi, research seemed like a solemn intellectual undertaking. It was too late to interview her grandfather, but in Queens, there were hundreds of men and women who had made the same journey that he had. And she knew that soon enough, no one living would remember Gottschee. Her task was to capture the stories of a community that was quickly dying out.

Her research couldn't have come soon enough. Every year, the group of Gottscheers who remember their birthplace shrinks. In 2005, she attended a meeting of the Gottscheer Relief Association that around 60 people attended. Four years later, when her research was complete, she attended another meeting and only 25 people showed up. Many Gottscheers had died in the interim.

But there are still a few old-timers left to ask about Gottschee. “My youth was beautiful,” says Albert Belay, a 90-year-old who left Gottschee as a teenager. He grew up in one of the dozens of small towns that surrounded the city of Gottschee. Most towns had a vivid German name, like Kaltenbrunn (“cold spring”), Deutschdorf (“German village”), and Hohenberg (“high mountain”).

“We were neighbors of the school building, and across the street was the church,” Belay remembers, with a warmth in his voice. Belay's childhood world was small and familiar. “8 o'clock in the morning, five minutes before, I left the kitchen table and ran over to school.”

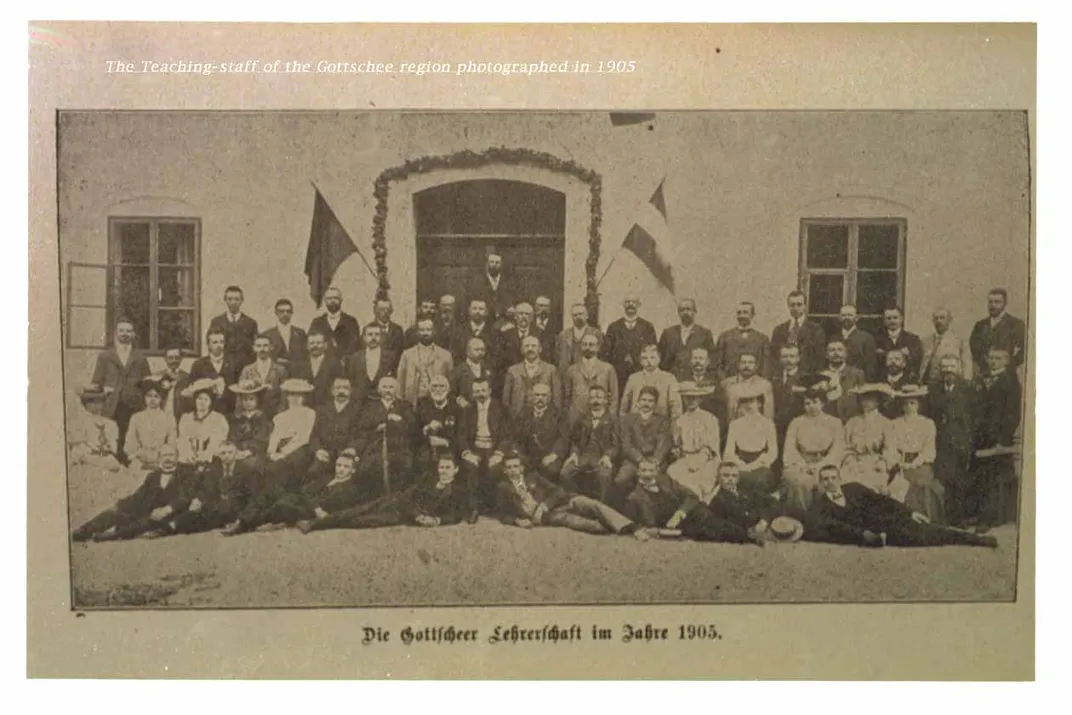

In school, Belay had to learn three alphabets: Cyrillic, Roman, and Old German—a sign of the many cultures that shared the lands around Gottschee. In high school, he had to learn Slovenian in just one year, because it became the language of instruction.

Edward Eppich lived on his father's farm in Gottschee until he was 11. His memories of his birthplace aren't particularly warm. “You had only maybe one or two horses and a pig, and that's what you live on,” Eppich recalls. When Austrians first settled Gottschee in the 1300s, they found the land rocky and difficult to sow. “It was not that easy,” he says.

These stories, and many more like them, helped add color to Bobbi's sketchy knowledge of her grandfather's generation. Her curiosity deepened. She learned German and decided to continue her interviews in Austria.

Bobbi's research told her that for hundreds of years, despite loose ties to central European empires, Gottschee was largely independent. For most of its history, it was officially a settlement of the Hapsburg Empire. But because it was on the frontier of central Europe, locals lived in relative poverty as farmers and carpenters.

In the 20th century, European borders were drawn and redrawn like letters on a chalkboard. In 1918, after World War I, Gottschee was incorporated into Yugoslavia. Locals complained, even proposing an American protectorate because many Gottscheer immigrants already lived in the US. But the area was insulated enough by geography and culture that none of these changes significantly affected Gottschee—until Hitler came to power in 1933.

At the time, pockets of German speakers were scattered across Europe, in countries like Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Yugoslavia. Some of those people wanted nothing to do with the Reich. Yet Hitler sought a homeland unified by the German language, and he expected far-flung communities like the Gottscheers to help build it.

There were undoubtedly supporters of Hitler in Gottschee. In the local newspaper, one local leader insisted that the rise of Germany would be good for Gottschee. “Wir wollen ein Heim ins Reich!” read a headline. We want a home in the Reich!

Still, many Gottscheers were illiterate—and thanks to a long history of isolation, they didn't easily identify with a nation that was hundreds of miles away. It's likely that, as in so much of Europe, many Gottscheers passively accepted Hitler's rule out of fear or indifference.

It's difficult to know what ordinary Gottscheers believed. Hindsight deforms the telling of history. Countless German historians have struggled to explain how World War II and the Holocaust happened at all. Lasting answers have been hard to come by—in part because In the wake of such vast atrocity, participants fall silent and bystanders belatedly take sides.

What Bobbi knew was that the horrors of World War II hung like a shadow in the minds of older Gottscheers. In Austria, a man invited Bobbi for an interview over lunch. The conversation was friendly until she asked, in imperfect German, about Hitler. His eyes grew dark and he started shouting. “To experience this, to live through this, you can never understand!” he said. “It's so easy to say 'Nazi' when you weren't there!”

As an American and a descendant of Gottscheers, Bobbi remains troubled by the connections between Gottschee and Nazi Germany. Even after years of research, she isn't sure what they deserve blame for. “There are pieces that they don't know, and also pieces that look different with the knowledge of hindsight,” Bobbi says. “And it's scary to wonder what they were a part of, without knowing it, or knowing incompletely.”

* * *

For the Gottscheers, life was better during the war than in the years that followed.

Gottschee was located in Yugoslavia when war broke out, but in 1941 the country was invaded by Italy and Germany. Gottschee ended up in Italian territory—and as such, residents were expected simply to give up the keys to their homes and resettle. They weren't told where they were going, or whether they would one day come back.

“You can't talk about Gottschee without the Resettlement,” one Austrian woman told Bobbi. “It is just like with the birth of Jesus Christ—there are years B.C. and A.D. You simply can't talk about before and after without it.”

“Everything came to an end in 1941,” says Albert Belay. “There was no way out. Europe was fenced in. Where to go? There was no place to go.”

Helen adds: “When Hitler lost the war, we also lost our home. We were homeless, we were refugees.”

Most Gottscheers were sent to farms in what was then Untersteirmark, Austria. Only upon arrival did they discover rooms full of personal belongings and meals left haphazardly on the table—signs that whole towns had been forcibly emptied by the German army. They had no choice but to live in those homes for the rest of the war.

When Germany surrendered in 1945, the Gottscheers lost their old home and their new one. Yugoslavia was seized by Josip Broz Tito and the Partisans, a resistance group had doggedly fought the Germans during the war. Both Gottschee and Untersteirmark were within the country's new borders, and the Gottscheers weren't welcome there.

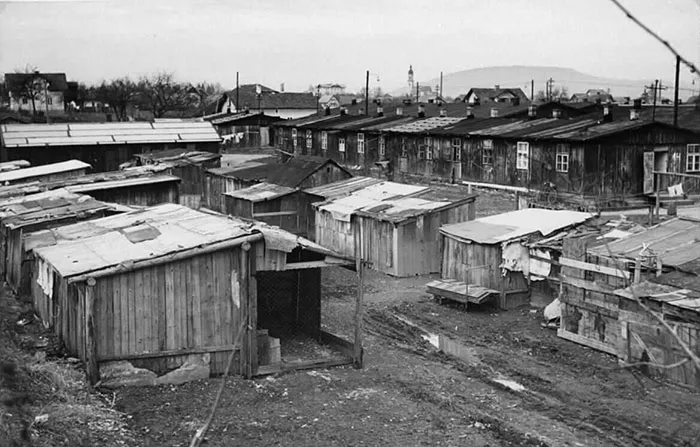

Herb Morscher was just a toddler when he left Gottschee, but he remembers the years after resettlement. “We were 'displaced persons,'” Morscher says bitterly. His family lived in a camp in Austria that had been designed to house soldiers. “We had to go and eat in a kitchen. We had no plates, no knives. We had nothing. They gave us soup, and you had to look for a couple of beans in there.”

By moving to Austrian territory, Gottscheers had technically rejoined the culture they had originally stemmed from. But Belay and Morscher say that Gottschee was the only homeland they really had. When Morscher attended school in Austria, he was labeled an Ausländer, or “foreigner.” By joining the Reich, says Belay, “we left the homeland.”

Perhaps it makes sense, then, that so many Gottscheers decided to leave Europe entirely. Family connections in the United States made emigration possible for a few thousand. Others gained refugee status or applied for residency.

Morscher moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where a cousin helped him integrate into Grover Cleveland High School. It was a painful transition. He had to wake up at 5 a.m. to practice the English alphabet. While Austrians had called him a foreigner, American schoolchildren heard his accent and called him 'Nazi.'

John Gellan, who grew up in Gottschee and recently turned 80, remembers the day he arrived in New York by ship. (His family was allowed to immigrate on the condition that Gellan join the U.S. military, which posted him on bases in Germany.) “We were parked outside the harbor of New York,” he says. “Our big impression was the higher buildings, and the many cars.”

He still remembers the exact stretch of New York's Belt Parkway that he could see from the ship. “All the traffic. It was like another world,” he says, and pauses. “Another world opened up, yes.”

* * *

Bobbi, for her part, discovered another world as she investigated her family's story. As she contacted Gottscheer organizations in New York in 2005, she thought of herself as a scholar helping preserve a disappearing culture. But her involvement soon became deeply personal. Just after Bobbi started her research in 2005, Helen got a phone call with good news.

Helen passed it down through the women of her family, first calling her daughter, Bobbi's mother. Bobbi's mother called Bobbi and explained, “The Miss Gottschee Committee wanted to ask if you would be Miss Gottschee,” she said.

It wasn't quite what Bobbi had bargained for. She was hoping to become a serious young researcher. Miss Gottschee, by contrast, is expected to deliver speeches at polka dances and march in parades wearing a banner and tiara. The two identities didn't seem particularly compatible.

But she had to admit that she was a descendant of Gottscheers, baking strudel with her grandmother, long before she was an aspiring graduate student. “They were both so excited that I would have this honor and this special role in the community,” Bobbi says. “At that moment, as a daughter and a granddaughter, there was no question that I was going to do this.”

More importantly, the yearly tradition of Miss Gottschee—along with the dances and parades and choir performances—were themselves proof that the Gottscheers were not a dying community at all. Every year, in a tradition that dates to 1947, over a thousand Gottscheers gather at a festival on Long Island. A Gottscheer cookbook frequently sells out at events, and orders have come in from Japan and Bermuda. And a second Gottscheer community in Klagenfurt, Austria passes down a different flavor of the group's heritage.

Bobbi had gone searching for a cultural graveyard, and found it overflowing with life.

* * *

The festival on Long Island—the Volksfest—is an odd and heartening sight. Just blocks away from suburban homes with broad driveways and carefully trimmed hedges, a huge crowd gathers around a long line of picnic tables. Boys and girls in traditional overalls and dresses run through crowds of Gottscheer descendants, while elderly men start sipping beer before noon.

At this year's Volksfest, women sold strudel and cake at an outdoor booth. At another, children and their grandparents paid a quarter to play a game that looked a little like roulette. The prize was sausage.

There was even a woman from Kočevje, Slovenia, in attendance. Anja Moric unearthed the Gottscheer story when, as a kid, she discovered an old Gottscheer business card in her parents' home. Eventually she discovered that Gottscheer communities still exist, and she connected with researchers like Bobbi to share what she'd found. It was as if, while digging a tunnel from one community to another, she had run headlong into someone digging a tunnel from the other end.

In the afternoon, Bobbi marched in a long procession of women who had once served as Miss Gottschee. She's becoming a regular at the festival—though it will take a few more years to rival the older Gottscheers who have attended more than 50 times.

Bobbi admits that there's a vast difference between being a Gottscheer and being a Gottscheer-American. When a few women gave speeches at the Volksfest, they stumbled over snippets of German. And it's easy to mistake the whole thing for a German-American gathering. Many Americans see sausage and beer and don't know the difference. Only small signs suggest otherwise, and they are easy to miss: the choir performances, the older couples speaking Gottscheerish, the reproduced maps of Gottschee and its villages.

Gottscheers could see Americanization as a small tragedy. But Bobbi thinks it's a triumph, too. “After centuries of struggling to have a space that was their space, they have it,” says Bobbi. “In this form that probably they could never have guessed would happen, centuries ago.”

There are echoes of the broader immigrant experience in the Gottscheer story. Egyptian restaurants opening in Queens sometimes remind Bobbi, unexpectedly, of the Gottscheers. But the Gottscheers also stand out in a few ways. There's an irony to their journey during World War II. During the war, they briefly became German—yet thousands of them ended up becoming American.

“What's really unique about the Gottscheers is the fact that the homeland that they had doesn't exist anymore,” Bobbi says. Their immigration story, which may seem familiar to many Americans, is more extreme than most because going home was never an option.

At times, Gottscheers wished it was. Bobbi's grandfather was told in Europe that the streets of America were paved with gold. The streets of New York were dirty and crowded. “He arrived in Brooklyn and said: If I had anything I could have sold for a ticket back, I would have,” Bobbi says.

On the whole, though, descendants of the Gottscheers looked forward. They took factory jobs or started pork stores or left home for college. Many encouraged their children to speak English.

In short, they integrated successfully—and that's exactly why Gottschee culture can't last. The blessing of the American mixing pot is that it can accommodate a staggering variety of cultural groups. The curse is that, in a mixing pot, cultures eventually dissolve. Integrating into a new place also means disintegrating as a culture.

Gottsheerish is going the way of the hundreds of regional dialects that fall into disuse each year. And Albert Belay says that's only one measure of what's lost. “It is not only the language,” he says. “It's a way of life in the language! That makes the bond between the people so strong. The language, and the habits—the past.”

Still, accidents can preserve culture for a time. Remnants persist in the fine print of a business card, the tiara on a teenager's head, the layers of an apple strudel.

Or in the sound of a violin. More than 70 years ago, Albert Belay brought one with him from Gottschee. His uncles played the instrument in Austria, and it's the only keepsake he has left. “They wanted me to learn,” he says. “The violin I kept, and I still have it here.”

Belay is 90, but the instrument brings back memories of childhood. “I'm back home, like. Every time I pick up the violin, I have a good feeling,” he says. “I'm well protected, like I was as a kid.”

This story was published in partnership with Compass Cultura.