‘Axis Sally’ Brought Hot Jazz to the Nazi Propaganda Machine

The voice of Nazi Germany’s U.S. radio disinformation campaigns would have had great success in the media landscape of today

:focal(1251x502:1252x503)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/93/c493dc39-5ae0-4913-b50a-3efe82d5b600/croppedv.png)

It was 2011 and Axis Sally was, once again, on the air. Shortwave radio enthusiast Richard Lucas, doing promotional work for his new book on the infamous American broadcaster employed by the Nazis, did a double take when he saw her name surface, via Google Alert, on a neo-Nazi website.

But sure enough, a podcast produced by the Northwest Front—which self-identifies as a “political organization of Aryan men and women who recognize that an independent and sovereign White nation in the Pacific Northwest is the only possibility for the survival of the White race on this continent”— featured a woman taking on the sobriquet that Lucas knew so well. Introducing this 21st-century version of Axis Sally was podcast host and founder of Northwest Front, American neo-Nazi Harold Covington.

“It was clear [Covington] had read [my] book,” says Lucas. “He started to describe Axis Sally as a very brave woman who withstood all kinds of things from the Führer and all that kind of stuff. And, of course, that wasn’t my intention writing the book. So it started to worry me quite a bit.”

Years earlier, Lucas had come across an online trove of the real broadcasts hosted by Axis Sally, whose messages were scripted by her married German lover to sow discord in the American armed forces and the homefront during the war. A freelance writer, Lucas used the recordings as an opportunity to dive into the true story of the woman behind the name, one Mildred Gillars. He combed through declassified federal documents and newspaper archives to write the first full-length biography on Axis Sally and her Reich Radio broadcasts—programs that ultimately made Gillars one of the few people ever convicted for treason in the United States.

“I was really trying to have a nuanced story of her and make her seem like a human being rather than a caricature,” says Lucas. “Especially today. People are not black and white; there are all kinds of tradeoffs that lead them to become who they are.”

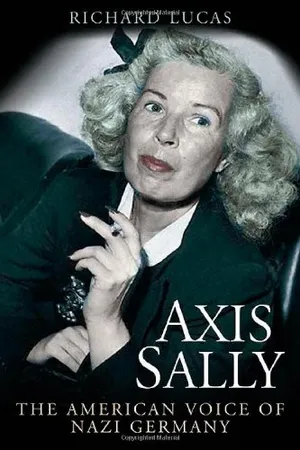

Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi Germany

One of the most notorious Americans of the 20th century was a failed Broadway actress turned radio announcer named Mildred Gillars (1900–1988), better known to American GIs as “Axis Sally.” Freelance writer and lifelong shortwave radio enthusiast Richard Lucas chronicles her life in her first full-length biography, Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi German. Lucas is currently working on his next book about journalist and broadcaster Dorothy Thompson.

While Gillars the person navigated a series of unhappy life events before she was recruited by Nazi propagandists as a radio talent, perhaps it’s not too surprising that the Nazi fantasy persona she embodied on-air was repurposed by modern-day white supremacists.

Gillars—born Mildred Elizabeth Sisk in Portland, Maine, in 1900—may not be as well-known as her contemporaries, like Lord Haw-Haw, voiced by the Irish-American William Joyce, or Tokyo Rose, whom American Iva Toguri D'Aquino was forced to bring to life. But Gillars’ work weaving together entertainment and propaganda feels, arguably, more at home in today’s culture, where extremist ideas enter the mainstream through the cult of personality.

For her part, Gillars vacillated easily between playing hot swing-era, big-band hits and denouncing the Jews, Franklin Roosevelt and the British on air. "One thing I pride myself on,” she’d say in a typical broadcast, “is to tell you American folks the truth and hope one day that you’ll wake up to the fact that you’re being duped; that the lives of the men you love are being sacrificed for the Jewish and British interests!”

She was very calculating, though, pushing back whenever she worried the text she was given to read on air went too far—“If she had something in the script that she thought was going to make her liable for treason in the future she fought it,” Lucas says.

“Midge,” as Gillars was called, always viewed herself as an entertainer. Growing up, she had dreams of becoming an actress. She suffered a traumatic childhood—reporter John Bartlow Martin, who covered her treason trial for McCall’s, wrote that she “grew up in the unhappy home of a drunken, incestuous father,” in reference to her stepfather Robert Bruce Gillars, whom her mother remarried when Midge was a child. When she left home, she studied drama and acting at Ohio Wesleyan University, but left school before receiving her diploma on the advice of a married professor—"the first of a series of intellectual older men whose influence shaped her fate,” Lucas notes in his book—in hopes of making it big.

Success never came. By the age of 31, disillusioned by her lack of theatrical success in New York, she followed a British-born man (Jewish, as it happened) to his posting in Algiers, where it appears that they were lovers, says Lucas. Their relationship must have dissolved shortly after, though, because when Gillars’ mother wrote to her to see if she wanted to join her European tour in Hungary in the spring of 1934, she followed. After mother and daughter met up in Budapest, the women traveled on, fatefully, to Berlin.

That was the year Adolf Hitler declared himself absolute dictator, the last vestige of Germany’s Weimar Republic falling to the Third Reich. While her mother was soon ready to return to the States, Midge, reluctant to return to a stalled theater career, decided to stay and study music. She found at job at the Berliz School teaching English, and thanks to a well-connected friend, she wrote, among other things, film and theater reviews for Variety (there, Lucas says, her writings betrayed her anti-Semitic sentiments). By 1940, she was badly hurting for money, though, and so she took a job at the German State Radio Corporation.

Josef Goebbels, the Nazi propagandist, had been looking for someone just like Gillars. In “Goebbels’ Principles of Propaganda,” Yale University psychology professor Leonard W. Doob summarized the Nazi propaganda chief’s philosophy that “the best form of newspaper propaganda was not "propaganda" (i.e., editorials and exhortation), but slanted news which appeared to be straight.” Goebbels leveraged this insight on many platforms, including short-wave broadcasts sent out by the Reich Radio Chamber. Short-wave radio has an expansive reach; Axis and Allied forces alike used it during the war to reach listeners throughout Europe and even across the Atlantic.

In 1941, a project at Princeton University studying the programs targeting U.S. audiences, issued the following assessment: “German commentators and news announcers have spent most of their breath trying to create attitudes of defeatism and distrust concerning Britain.” To do so, the Nazis played up the race, class and cultural divisions already manifest in the U.S. “Berlin programs for this country are employing corrosive anti-Semitic propaganda, together with conflicting appeals to workers, businessmen, isolationists, interventionists, racial and national groups,” the paper wrote. These programs also included radio theater, like one “pro-Nazi, anti-British dramatization of the life of Lincoln.”

But Goebbels knew the Teutonic accents aired on his broadcasts were getting in the way of the effectiveness of the content. Voiced by Germans, the messaging just didn’t have the same punch it would if it was delivered by someone with a more familiar, Midwestern voice. He needed someone who could speak to Americans in their own speech patterns, and Gillars was just the woman for the job.

According to the dossier of her 1949 treason trial, when Gillars began, “her duties were those of an announcer introducing programs and an actress in dramatic and cabaret broadcast.” By all accounts, she never expected the U.S. to enter the war. “She was basically frozen in an isolationist viewpoint of a woman who was still in the 1920s—we’re not going to fight another war for Britain and France; we are going to stay out of this war,” says Lucas. Pearl Harbor, he says, took her bitterly by surprise. But she didn’t go back to the U.S. after the Japanese attack—her passport, for one, had been confiscated by a less-than-sympathetic U.S. embassy official in the spring of 1941. She had also gotten engaged to a German physicist who said he wouldn’t marry her if she returned to the States.

Worried she was too old to find another partner, she stayed. Her fiancé died on the Eastern Front, but Gillars didn’t remain alone long—she soon became seriously involved with the married Max Otto Koischwitz. Once a professor of German at Hunter College in New York until his Nazi sympathies pushed him out of academia, he was now an official of the German Foreign Office. He became yet another older male mentor for Gillars, says Lucas, and after Koischwitz was put in charge of the Nazi radio broadcasts targeting U.S. troops, he arranged for his lover to work under him.

Now Gillars was directly amplifying Nazi state propaganda, starring in the programs and radio plays that Koischwitz wrote for her. Accounts by U.S. troops show they found these screeds, intended to weaken the morale of the GIs, something of a joke: “In far off Berlin, Minister Goebbels thinks that Sally is rapidly undermining the morale of the American doughboy but our corporal knows that just the opposite is happening. He gets a bang out of her. All the U.S. troops love her,” explained Norman Cox in Radio Recall, the journal of the Metropolitan Washington Old-Time Radio Club.

The reason they tuned in was, in part, because she played live jazz music, a tactic she convinced her superiors to adopt.

As one 1944 column in the Saturday Evening Post put it: “There’s nothing quite so good for a soldier's morale as a little swing music now and then. Good, groovy, solid swing. That's where the radio is playing a big part in winning the war.”

“She was bringing something very American and very showy to Goebbel’s lineup,” says Lucas. “[The Nazis] didn’t have the kind of capability to do that. Most of the people who knew how to do radio, the dramatists, they left Germany by 1939 and went into exile.”

Gillars also conveyed information about Americans in German prison camps, which is the way many listeners back home would receive news of the status of their loved ones. With an eye toward self-preservation, though, she was always careful to make sure that nothing she read crossed over into the realm of treason. That’s one reason she was so upset when she found out another woman, Rita Luisa Zucca of New York, was also calling herself “Axis Sally” on the Italian state airwaves; she didn’t want to be held accountable for anything the other Sally said. Among other things, Zucca had discussed military intelligence on her programs in an attempt to confuse the advancing Allied troops.

Gillars took pride in her performances on Berlin state radio, so much so that she squirreled away her best broadcasts, even preserving them after Nazi Germany fell. “She was a narcissist. That’s the thing. She was basically a show person,” Lucas says.

But unlike Zucca, who renounced her U.S. citizenship prior to the war and married an Italian national, ensuring she couldn’t be tried for treason in the U.S., Gillars was vulnerable when the war ended. She was so besotted with Koischwitz that she believed until the end that he was going to leave his wife and marry her. After a bombing killed the wife in 1943, she thought it was just a matter of time, but Koischwitz died himself in 1944, leaving her without the cover of German citizenship by marriage, which would have meant she no longer owed allegiance to the U.S.

Gillars blended in with the masses of displaced persons following the fall of Nazi Germany, until the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps caught up with her in 1946. Koischwitz was still on her mind: “When they finally caught her, the U.S. interrogator said, ‘Why did you stay?’ ‘Why didn’t you run?’ She said, ‘I never thought he would die,” says Lucas.

She was held in internment camps until she was brought back to the U.S. to face trial in 1948. “Both her trial and Tokyo Rose’s trial happened within months of each other,” says Lucas. “They could have let them go. It had been two years since [Gillars’s] capture, three years since end of war. But there were political considerations.” 1948 was, after all, a presidential election year, with incumbent President Harry S. Truman looking to gain political favor in the race against New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey.

Of the ten counts of treason Gillars was initially charged with (eventually reduced to eight), she was only convicted on one, for her role in Vision of Invasion, a radio play written by Koischwitz in which Gillars starred as an Ohio mother who had a dream about her son being killed in the Allied Invasion of Europe.

A jury levied a fine of $10,000 and sentenced her to 10 to 30 years in prison, though she was released after 12. During her time behind bars, she converted to Catholicism and upon release, the Catholic Church arranged for her to teach at a convent in Columbus, Ohio. Later, she found work tutoring local high school students and finally graduated from Ohio Wesleyan, fittingly with a degree in speech.

According to Lucas, her neighbors had no idea about her past life until the media came calling after her death in 1988.

It’s not a far stretch of the imagination to suppose things might have gone differently if she were around today. With an ability to keep people listening by packaging propaganda among radio hits and scoops, and an eye for toeing the line just so, had she wanted to, it’s easy to see her making having a second act in media. “She would go through a period of two years three years where she’d be considered persona non grata, she’d do her apology, hire a PR firm that would help her rehabilitate her career, and she’d be back,” Lucas agrees. “When I see some of these people who were [shunned] 15 years ago and are back at it…it almost feels like her ghost.”

Instead, while Axis Sally appeared briefly in the 2008 Spike Lee film Miracle at St. Anna, and a screenplay about her life is currently in the works, she’s mostly disappeared from popular knowledge.

While Lucas spent six-odd years thinking about Gillars’ life for his book, he says he still wonders about her. While she always swore that she had no knowledge about the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question,” one woman who was close to her in Columbus surprised him when she mentioned that one of Gillars’ most prized possession was a cup that had been given to her by Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS. If she was hobnobbing with Himmler, says Lucas, that implied she had access to inner circle information.

“How much did she know?” he asks.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.