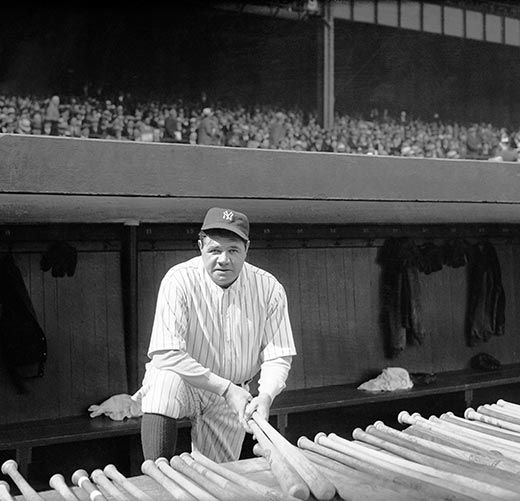

Baseball’s Bat Man

When stars like Derek Jeter ask to customize their baseball bat, Chuck Schupp makes sure they get what they want

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/baseball-bats-in-dugout-631.jpg)

Chuck Schupp has delivered alchemy to major-league players for 27 years, listening to their wishes for the perfect bat and then getting his team at the Hillerich & Bradsby plant in Louisville, Kentucky to produce one that fits their fancy.

When Texas Rangers outfielder Josh Hamilton put on a herculean display at the 2008 Home Run Derby, Schupp fielded calls from players, including slugger David Ortiz of the Boston Red Sox, who wanted to know what bat he was using—a C253 model originally made for Jeff Conine, a solid journeyman who played 17 seasons.

“Everybody’s different,” says Schupp, the pro baseball division manager for the venerable bat company. “Some guys never waver at all [in their bat choice]. Some guys tweak their stuff. Part of the challenge is reading the personalities of the guys.”

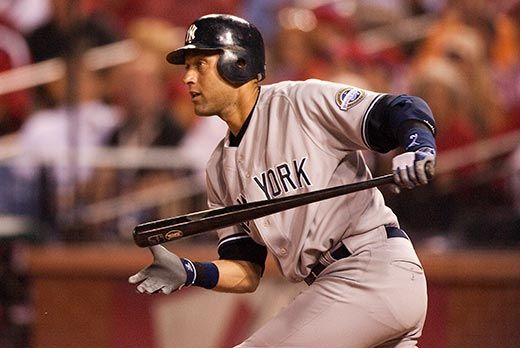

Derek Jeter of the New York Yankees has used a 32-ounce P72 bat since his days in the minor leagues nearly two decades ago. “He just reloads,” Schupp says. “When I look at the guys I’ve dealt with, the guys that are really good don’t change. ARod [Alex Rodriguez], Jeter, Ryan Howard, Jim Thome. Most of the guys that are really good for a long period of time find something they’re comfortable with and stick with it. They reduce the opportunities for failure. They fail most of the time anyway, so why muddy the water with five bat choices?” Custom bats were born in 1884 when J.A. “Bud” Hillerich, an apprentice woodworker, sneaked out of the shop to watch a baseball game. Pete Browning, the star slugger of the Louisville Eclipse, broke his bat that day and Hillerich, 18, invited him back to the shop to create a new one. They worked through the night with Browning periodically taking a practice swing to check the evolving model. The next day, he smacked three hits with it; the Louisville Slugger was born.

Schupp is a barometer of the changing tastes of players over the past three decades. When he began, the Louisville Slugger dominated the market with bats made from white ash (Fraxinas americana) grown in the forests of Pennsylvania and New York. In those days, only about five companies supplied bats to players; now, about three dozen firms supply hundreds of models of bats to major-league clubs although most are variations on just four models. The model names mentioned below are specific to H&B, but other makers take their bats and modify them as their players request. If you think those models debuted in the hands of Hall of Famers, you’d be mistaken. One of the benefits of being a major leaguer was that custom bats were paid for by the team. As such, even the most mediocre of players had their own customized weapons at the plate.

Legendary Minnesota Twins and California Angels infielder Rod Carew wielded a C243 while winning seven batting titles, but the original was made for Jim Campanis (son of big league player and executive Al Campanis), a career .147 hitter who played only 113 big league games in the late 1960s. Another example is the C271, a bat with a cupped end (to reduce weight) fashioned after a bat that outfielder José Cardenal got in the early 1970s from a teammate who played in Japan. The third model is the T85, originally made for “Marvelous” Marv Throneberry, a .237 hitter best known as a punch line during the early years of the New York Mets, and later used by George Brett, a three-time batting champion. The fourth is the I13 model made for Mike Ivie, who hit .269 in 11 mostly struggling seasons, now swung by all-stars Evan Longoria of the Tampa Bay Rays and Albert Pujols of the St. Louis Cardinals.

“I think we’ve made all the models we’re going to make until I walk in the clubhouse again,” Schupp says. “Everything starts out as a request or an oddity. That’s the fun part of it.”

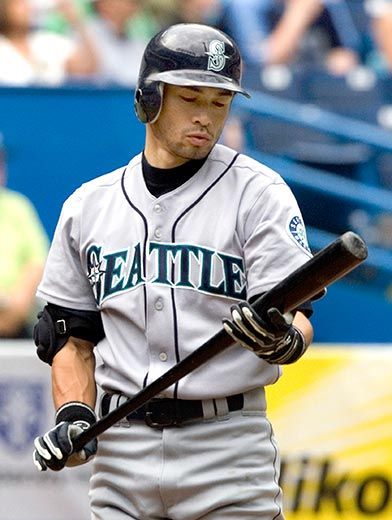

Players’ relationships with bats have inspired any number of myths and tales. Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural centered around Wonderboy, the lightning-tempered bat swung by Robert Redford in the movie version. Richie Ashburn, the slap-hitting outfielder for the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1950s, slept with his bat when he was on a hot streak. Ty Cobb rubbed his bats with tobacco juice to keep out moisture. Babe Ruth carved 21 eyelash notches in the Louisville Slugger that swatted 21 home runs during the 1927 season. Dante Bichette, the slugger who played 14 seasons mostly in the 1990s, held his bats up to his ear and pinged them; he was convinced that the higher the pitch, the more solid the wood. Ichiro Suzuki, the Seattle Mariners batting champion, keeps his bat in a silver case.

Schupp has watched bats get lighter as players weaned on the whippy aluminum bats used in high school and college have advanced to the pros. Babe Ruth used an R43 model that was 35½ inches long and weighed 38½ ounces made from hickory when he hit 60 home runs in 1927. By the time Hank Aaron was breaking Ruth’s record in 1973, he used an ash bat that was a similar model, 35 inches long weighing 33 ounces. Rodriguez swings a 34-inch, 31-ounce model. As the long season wears on them, Schupp says some players request bats a half ounce or ounce lighter.

The biggest change has been the shift to maple bats. Eleven years ago, Schupp was at spring training when he saw one player after another trying Sam Bats, as they were called, hitting sticks made by the Original Maple Bat Company from Ottawa, Ontario. He went back to his bosses and told them there would be a market for maple. When Barry Bonds hit 73 home runs in 2001 with a maple bat, their popularity soared. Today, maple and ash are about equally split among major leaguers, fueled partly by the perception among players that the ball flies off maple bats faster.

“It doesn’t,” Schupp says, and research commissioned by Major League Baseball backs him. In 2005, the league spent $109,000 for Jim Sherwood of the Baseball Research Center at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell to study the differences. He concluded that the batted ball speeds for ash and maple were essentially the same. “You’re talking physics versus clubhouse logic,” says Schupp. “The exit velocity is not any different. But it’s a harder, dense grain so it does fray less.”

Maple has a different problem. It shatters when it breaks, sending splintered projectiles into the field. After so many bats turned into weapons during the 2008 and 2009 seasons, Major League Baseball commissioned a study, then implemented regulations that required a minimum wood density, outlawed soft maple bats, reduced the diameter of barrels and increased the minimum diameter of handles. The rate of maple bats breaking dropped 35 percent from 2008 to 2009 and another 15 percent this season, according to Major League Baseball.

In September, though, Chicago Cubs outfielder Tyler Colvin, while running toward home plate, was struck in the chest with a splintered bat. He spent three days in the hospital for treatment of the puncture wound. The injury renewed calls from some players and managers to ban maple bats. Earlier this year, Tampa Bay Rays manager Joe Maddon said “The maple bat is turning into the Claymore mine of baseball,” adding that it was only a matter of time before someone was impaled. “I don’t like it... Something needs to be done.”

Major League Baseball officials said they would seek to expand the existing regulations to make handles thicker and barrels thinner during the off-season. Schupp says with six months lead time or more, Hillerich & Bradsby could harvest enough ash (despite an eight-year ash blight that’s hit Northeast forests), but he doesn’t think Major League Baseball will ban maple, the latest craze. “The customer—the ballplayer—more than half of them ask for maple,” he says. “The players want it. That’s the tough thing.”

Ultimately, Schupp and the craftsmen at H&B as well as the other bat makers are trying to create—recreate, really—something as elusive as a World Series-ending home run—feel-good wood. Two bats may be the same length, the same weight and the same shape yet feel entirely different.

“I pick ‘em up and if they feel good, then I use them,” said Wade Boggs, the Hall of Fame batting champion. “It’s all feel.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)