Baseball’s Glove Man

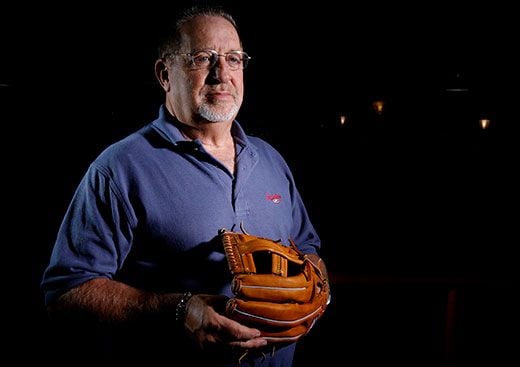

For 28 years, Bob Clevenhagen has designed the custom gloves of many of baseball’s greatest players

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Baseball-gloves-Bob-Clevenhagen-631.jpg)

At spring training about two decades ago, a young shortstop named Omar Vizquel mentioned to Bob Clevenhagen that he needed a new glove as soon as possible. Clevenhagen, the glove designer for Rawlings Sporting Goods, said he had one ready, but it would take a few days to imprint the ”Heart of the Hide” logos and other markings. Without them, Clevenhagen said, he could have a new glove shipped by the next day.

Vizquel opted for unadorned and it’s proved to be a wise choice. Over a career spanning 23 seasons, he has won 11 Gold Gloves for fielding excellence. Still robbing hitters at age 44 for the Chicago White Sox, the venerable infielder has remained true to his Pro SXSC model.

“Even today, we make his glove with no writing on it,” Clevenhagen says, noting the request is only partly a ballplayer's superstition. “It also guarantees the fact I made the glove for you. We didn't pull it off the shelf and ship it.”

Clevenhagen is known to many as the Michelangelo of the mitt. Since 1983, he has designed gloves (and occasionally footballs and helmets and catcher's gear) for the sporting goods firm best known as the Gold Glove Company. He is only the third glove designer in the history of the company, following the father-son team of Harry Latina, who worked from 1922 to 1961, and Rollie Latina, who retired in 1983.

Clevenhagen apprenticed with Rollie for a year before settling in to his position 28 years ago. Since then, he’s designed gloves for any number of major-league players including Alex Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, Torii Hunter, Mark McGwire and Hall of Famers Ozzie Smith, Robin Yount, Mike Schmidt and Cal Ripken Jr. He even designed a glove—a big glove—for the Phillie Phanatic. Nearly half – 43 percent – of major leaguers use Rawlings gloves.

Rawlings became synonymous with baseball gloves in the 1920s after St. Louis pitcher Bill Doak, then famous for his spitball, suggested his hometown sporting goods company connect the thumb and forefinger of a glove with webbing to create a small pocket. Previously, players dating back to the 1870s had worn gloves as protection (one early wearer used a flesh-colored glove in hopes of going unnoticed so opponents wouldn’t think him less of a man).

The Doak model glove, which Rawlings sold until 1949, drastically changed the game. ”A reporter once said the original designers, father and son, probably did more to do away with the .400 hitters than pitchers did,” Clevenhagen says.

Today's gloves dwarf those of the 1940s and 1950s. The Rawlings mitt Mickey Mantle used in his 1956 Triple Crown year, for instance, resembles something a Little League tee-ball player would use today. “It's sort of flat and it doesn't actually close easily because of the bulk of the padding, so you've got to use both hands,” Clevenhagen notes.

In 1958, Rawlings began making its XPG model in response to Wilson’s A2000, which had a larger web, a deeper pocket and less padding than previous models. With Mantle’s autograph on it, the glove quickly became Rawlings most popular model. It introduced “Heart of the Hide” leather, the “edge-U-cated heel”and the “Deep Well” pocket, still offered on gloves today.

Those Sportscenter highlight catches pulling home run balls back from over the fence wouldn't have happened 50 years ago, he notes, because players had to use two hands to keep the ball in the gloves of the era. "Today, the glove can make the catch for you,” Clevenhagen says. “You get that ball anywhere inside the glove, the way it's formed with the fingers curved, the webbing deeper, and it just makes all the difference in the world."

During his early years on the job, one of the first designs Clevenhagen made was for Dave Concepcion, the perennial all star shortstop for the Cincinnati Reds. He changed the back of Concepcion’s Pro 1000 to make it deeper and easier to break in. Another early project was redesigning the Rawlings signature softball glove. Clevenhagen played a lot of fast pitch softball in those days and the typical glove design was just to add a few inches in length to a baseball glove. He made a pattern with a wide, deep pocket, spreading the fingers suitable for the bigger ball, a model RSGXL that’s still sold today. Over the years, he’s also designed gloves for young players with physical disabilities such as missing fingers that make it difficult or impossible to use regular gloves.

Dennis Esken, a Pittsburgh-area historian and glove collector who owns three game-used Mickey Mantle mitts and has owned a host of gloves worn by All Stars, says Clevenhagen has made gloves more streamlined and, in particular, lightened and improved catcher’s mitts. “He’s made them easier to use, more functional,” adds Esken, who speaks regularly with Clevenhagen.

Gloves are now designed with every position in mind, not just first base and catcher, which traditionally have used specialized mitts. The differences are more than just the appearance and size, but in the interior changing how the glove closes around the ball. “For outfielders, the ball will be funneled into the webbing. They are more apt to snag the ball up high in the web,” Clevenhagen says. “An infielder wants the ball where there's no problem finding it with his bare hand, not in the webbing, but at the base of the fingers.”

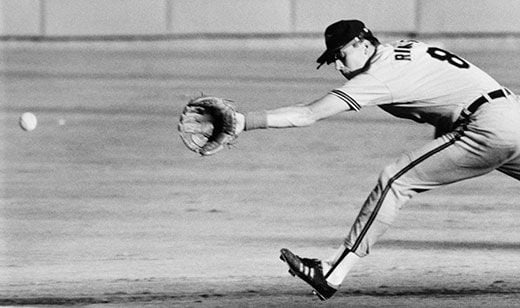

Most players today grew up brandishing a retail version of the glove they flash in the big leagues. Alex Rodriguez now has his own model, but for years he used the same model as his hero, Cal Ripken, a Pro 6HF. When Ozzie Smith, the St. Louis Cardinals acrobatic shortstop, began brandishing a six-finger Trap-Eze model made famous by Stan Musial in the 1950s, a generation of young shortstops followed suit. Clevenhagen says 99 percent of the players use the same model their entire career. "There’s just something about it,” he adds. “They just can’t bring themselves to try something different."

In past years, players like Dwight Evans of the Boston Red Sox, Amos Otis of the Kansas City Royals and pitcher Jim Kaat, who won a record 16 Gold Gloves, hung on to their favorites, their “gamers,” for a dozen years or more, repeatedly sending them to Rawlings to be refurbished. Mike Gallego, then a shortstop with the Oakland A's, went back into a darkened clubhouse during the World Series earthquake of 1989 to retrieve his glove, an eight-year-old RYX-Robin Yount model.

Now young players don’t want to spend weeks breaking in a new glove. Sometimes, they don’t get through a season with the same gamer. One reason, he says, is that the materials are better and the gloves are more consistent. “We used to go to spring training with 50 of a certain model and go through 47 before a player found one that felt right,” he says. “Now, they're happy right off the bat.”

Some players still name their favorites. Torii Hunter, the Los Angeles Angels outfielder and a nine-time Gold Glove winner, has three or four gamers, each with a name. Over the years, he's taken Coco, Sheila, Vanity, Susan and Delicious into the field with him. When he makes an error with one, he sets it aside, like a petulant child being sent to the corner, until he thinks it’s ready to return.

“It's like a relationship, you just know,” Hunter said earlier this year. “You start dating a girl, you hang out with her a couple times, you know this is the one for you. After a year, you get comfortable and you figure out whether she's the real deal.”

Clevenhagen, who figures he’ll retire in a few years, is careful to put his contribution into perspective. One of his favorite players, Ozzie Smith, exchanged his XPG12 model for a new gamer regularly.

“A pro player could probably play with anything,” he adds. “I always thought it didn't matter if Ozzie had a cardboard box on his hand. He'd still be the greatest shortstop ever.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)