What Made the Battle of Blair Mountain the Largest Labor Uprising in American History

Its legacy lives on today in the struggles faced by modern miners seeking workers’ rights

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/e9/16e9483a-3b97-4f42-a833-a3ec5b69af6e/blair-after-the-battle-4a.jpg)

Police chief Sid Hatfield was a friend to the miners of Matewan, West Virginia. Rather than arresting them when they got drunk and rowdy, he’d walk them home. For his allegiance to the unionized miners of southwestern West Virginia, rather than the say, the nearby coal companies who employed them, Hatfield was gunned down on August 1, 1921, on the steps of the Welch, West Virginia, courthouse, alongside his friend Ed Chambers as their wives looked on in horror. Their murder catalyzed a movement, the largest labor uprising in history, that remains resonant to this day.

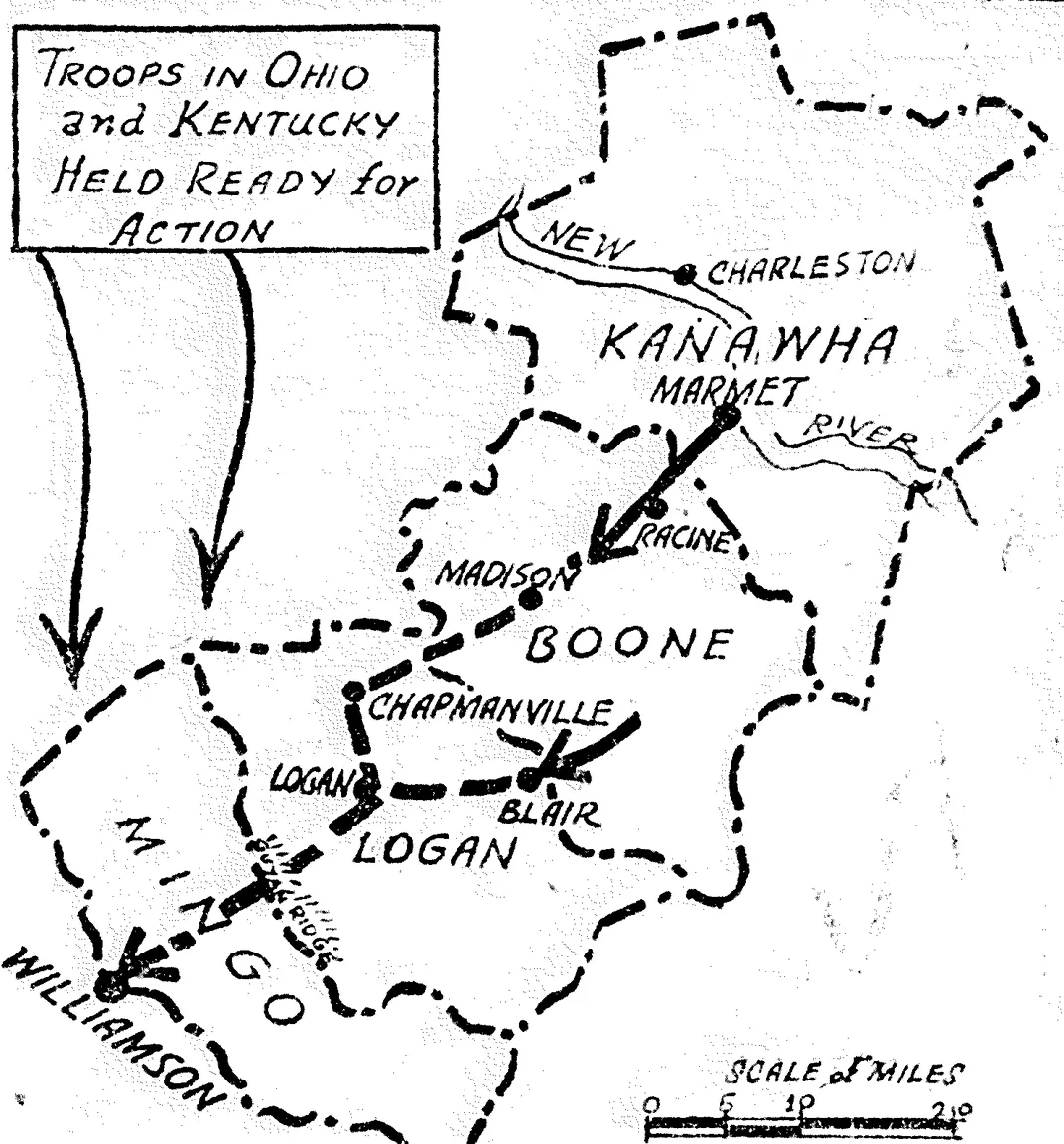

The Battle of Blair Mountain saw 10,000 West Virginia coal miners march in protest of perilous work conditions, squalid housing and low wages, among other grievances. They set out from the small hamlet of Marmet, with the goal of advancing upon Mingo County, a few days’ travels away to meet the coal companies on their own turf and demand redress. They would not reach their goal; the marchers instead faced opposition from deputized townspeople and businesspeople who opposed their union organizing, and more importantly, from local and federal law enforcement that brutally shut down the burgeoning movement. The opposing sides clashed near Blair Mountain, a 2,000-foot peak in southwestern Logan County, giving the battle its name.

The miners never made it past the mountain, and while experts don’t have a definitive death toll, estimates say about 16 miners died in the fighting, although many more were displaced by evictions and violence. Despite the seemingly low death toll, the Battle of Blair Mountain still looms large in the minds of today’s Appalachian activists and organizers as a time when working class and impoverished Americans came together to fight for their rights. For some advocating for labor rights today, the battle also is a reminder of what poor Appalachians are capable of.

Miners then often lived in company towns, paying rent for company-owned shacks and buying groceries from the company-owned store with “scrip.” Scrip wasn’t accepted as U.S. currency, yet that’s how the miners were paid. For years, miners had organized through unions including the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), leading protests and strikes. Nine years prior to Blair Mountain, miners striking for greater union recognition clashed with armed Baldwin-Felts agents, hired mercenaries employed by coal companies to put down rebellions and unionizing efforts. The agents drove families from their homes at gunpoint and dumped their belongings. An armored train raced through a tent colony of the evicted miners and sprayed their tents with machine gun fire, killing at least one. In 1914, those same agents burned women and children alive in a mining camp cellar at Ludlow, Colorado.

This history of violence against the miners and their families, combined with low wages, dangerous jobs and what amounted to indentured servitude with a lifetime of debt were all contributors to the Blair Mountain uprising. Hatfield’s murder lay atop these injustices. On August 25, 1921, it all boiled over and miners marched toward Mingo, where they hoped to force local deputies to lift the strict martial law that inhibited union organizing.

According to Chuck Keeney, historian and descendant of key labor leader Frank Keeney, the miners swore themselves to secrecy over who was leading them to avoid legal retaliation. This meant that no single “general” led the miner army, although they did think of themselves as an army, and not just as peaceful protestors. Keeney says they were rebelling against the mine guard system, but they were also avenging the death of their friend. While the miners may have been a ragtag group, full of secrets, Keeney argues they were still well organized, as do historians who’ve recorded the history. In Thunder in the Mountains, a thoroughly reported historical account of the battle, author and historian Lon Savage describes a testy, oppressed and angry group of laborers.

“They had been crushed and killed on their jobs and fired from them when they tried to organize a union,” Savage wrote. “They had been evicted from their company homes and machine-gunned in their union tents. Periodically they had risen in fury.”

The two sides fought for days, shooting stray bullets back and forth in mountain passes on the march to Mingo. With gunfire being exchanged throughout the march and in wooded, sheltered areas, it was difficult to ascertain, and even now, how many men were shot or injured at any given time. Before and during Blair Mountain, Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin ruled the region and sided with local coal operators, hoping to put down the rebellion and restore order in his jurisdiction. He helped organize a raid on the town of Sharples on August 27, when around 70 police officers fired at opposing miners. Two miners were killed, but as people ran from town to town the rumored death toll grew like a big fish story. Savage wrote that miners told each other bodies were stacked up after the raid. Later in the skirmishes, with the help of deputized townspeople, Chafin dropped homemade pipe bombs on the marchers.

According to Keeney, the miners’ doomed mission was the “closest thing to a class war” our country has seen. On September 2, 1921, President Warren G., Harding heeded West Virginia lawmakers’ requests for federal troops. Their presence persuaded the miners to throw down their guns and surrender, as many were veterans themselves and refused to fight against their own government. They sought to wage war not against the United States but against coal operators. Keeney says it’s not clear what would've happened had the miners continued, but anything is possible.

“If they had continued to fight, they would have broken through, probably,” says Keeney, who wrote a book about the labor uprising, Road to Blair Mountain. In an alternative history, a miner coalition could have overwhelmed the local police force and coal-employed fighters to push forward on the march to Mingo. There, they might have lifted martial law, freed jailed coal miners and made good on a popular miner’s tune, “We’ll Hang Don Chafin From a Sour Apple Tree.”

After Blair Mountain, small victories and bigger losses would change the landscape of union organizing. Labor leaders, including Keeney’s ancestor Frank Keeney, were cleared of charges related to the insurrection. Other miners were freed from jail as well, because as Savage wrote, coal attorneys were discouraged and dismissed indictments; juries in West Virginia counties often sided with miners instead of coal companies. But membership in the United Mine Workers of America plummeted; continued strikes cost the UMWA millions and made little headway toward their goals of changing coal company policies. UMWA membership peaked around 1920, with 50,000 members, but fell to just 600 in 1929. Later, it would rise and fall again, following a roller coaster of peaks and declines throughout the 20th century.

Despite the ultimate surrender, one of the many bits of Blair Mountain history that continues to stick out is the diversity of the miner’s army. In 1921, coal company towns were segregated, and Brown v. Board of Education was decades away. However, Wilma Steele, a board member of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, says Matewan was one of the only towns in the United States where Black and white children, most commonly Polish, Hungarian and Italian immigrants, went to school together. Other miners were white Appalachian hill folk. Most all were kept apart in order to prevent organization and unionization. It didn’t work. Keeney recalls one incident during the Mine Wars, Black and white miners held cafeteria workers at gunpoint until they were all served food in the same room, and refused to be separated for meals.

“We don’t want to exaggerate it and act like they were holding hands around the campfire, but at the same time they all understood that if they did not work together they couldn’t be effective,” Keeney says. “The only way to shut down the mines was to make sure everybody participated.”

This year, the Mine Wars Museum marks that unity in the first Blair Centennial celebration. Kenzie New, the museum’s director, says planning has been somewhat fluid because of ongoing COVID-19 concerns, but will start with a kickoff concert in Charleston, West Virginia, on Friday, September 3. The UMWA will retrace the miners’ 50-mile march over the weekend, and end with a rally on Labor Day.

The Blair Centennial serves as a reminder, says New, that solidarity is the only way forward.

“New labor and justice conflicts are emerging in West Virginia and throughout the nation,” New says. “Blair Mountain teaches us that we have to stand together if we’re going to win. The miners took great risks and banded together collectively, overcoming barriers of race and ethnicity, to shine a light on these dramatic examples of exploitation.”

It’s true that the miners didn’t defeat Chafin and his deputized army. It’s also true they threw down their guns when federal troops were called in. But to many, they didn’t exactly lose. By surrendering only to the federal government and not to local authorities, they proved they were a force to be reckoned with.

“It was Uncle Sam did it,” a miner yelled as he leaned out of a passing streetcar during the retreat. Savage wrote in his book that the miner “expressed the pride of all that neither Sheriff Chafin nor [West Virginia] Governor [Ephraim] Morgan had stopped their march.”

Appalachians today find inspiration in that attitude and the organizing of the 1920s. Videos posted by younger generations on social networks like TikTok are reminiscent of what New and others have said: Appalachia may not always win its labor battles, but its people have a high tolerance for fighting for what’s right, even when the odds of victory are slim. The lesson best learned from Blair Mountain is simple resilience.

Today’s coal miners face similar battles, though the specific injustices and locations have changed detai. Wes Addington, executive director of the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, who began taking on black lung disease cases more than a decade ago, says the spread of the illness has gotten worse in recent decades as miners are exposed to higher levels of rock silica. With richer coal seams having been fully extracted, miners must resot to smaller seams that require adjacent seams of rock to be mined along with it.

“It’s really an exhausting process to watch someone you care a lot about slowly die from a disease that causes you to have a little less breath every day,” Addington says. “And the next day is a little worse.”

“Every miner’s lungs are black if they’ve worked in a mine any significant period of time,” adds Kentucky state representative Angie Hatton, whose husband has black lung. “It takes something pretty awful for them to admit any sort of weakness or physical limitation. And by the time they get to that point they’re near death.”

Local black lung support groups and the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center help miners get black lung benefits in court, but it’s not an easy task. After a Kentucky state law changed what kind of medical testimony was allowed during trial, Ohio Valley Resource reports, Kentucky miners diagnosed by state-approved experts as having the disease fell from 54 percent before the change to 26 percent in 2020. In short, even as black lung is getting worse for the miners, it’s become harder to claim health benefits and receive appropriate care because of new legislation.

In a more direct parallel to the struggles of the Blair Mountain marchers, miners in Alabama are now in their fifth month of strike as they fight for higher pay. Miners are particularly upset because they took massive pay cuts to save the Warrior Met coal company from bankruptcy and have gotten none of the raises and benefits promised for their sacrifice. In 2016, Warrior Met, a global supplier that mines the kind of coal needed for steel production, reached an agreement that included severe cuts to pay, health care benefits, time-off from work and more.

Braxton Wright, a Warrior Met miner, says morale is on a bit of a roller coaster. The local UMWA holds solidarity meetings and cooks meals for miners, families and the community each week. Miners are also getting strike pay from the union and are supported by a food pantry. Wright, whose father and grandfather were miners, say striking workers are attacked on the picket lines regularly. They’ve had five instances in which non-union workers who break picket lines try to ram picket lines with their vehicles.

Warrior Met operates today without a contract, even though it has two union coal mines in the region. Wright says they’ve received a lot of solidarity from other retail, theater and even media unions, some of whom marched in a picket line with the Alabama miners. The solidarity with unexpected allies may be surprising, but so are environmental concerns miners have about nearby waterways, which Wright says has been polluted by coal runoff. They fought for a pollution check on the Warrior River; these are not backwoods miners unconcerned by climate change and pollution.

Despite the shrinking populations in Appalachia today, not to mention the continued fight for earned wages, anti-union sentiment and so many more struggles, the region finds a way to commemorate its own heritage. The Blair Centennial is only one example of the important labor history that brought diverse groups of people together 100 years ago. Today, union workers, their families, and activists of all stripes look back on Blair Mountain for inspiration about how to fight today’s battles and for lessons on how to persevere.

One thing Wright knows for sure: Coal miners and their families know how to endure.

“We will take care of each other,” Wright says. “One of the [Warrior Met] negotiators has said ‘We’ll starve y’all out.’”

“You won’t starve us out.”

Editor's note, August 26, 2021: This story has been updated to reflect how miners are exposed to higher levels of rock silica.