Go Behind the Glass of Churchill’s Underground War Rooms

Exploring the secrets of the storied bunker—from its well-worn maps to a leader under extreme duress

“This is the room from which I will direct the war,” declared Winston Churchill in May, 1940, after he entered an underground bunker below the streets of London. The newly minted prime minister surveyed the space, readily aware that England could be under Nazi attack at any moment.

The Cabinet War Rooms, as the bunker was called, didn’t fall into Churchill’s lap. Four years prior, when he was relegated to a position as a backbench MP, he had advocated for an underground bunker where government staff, military strategists and the prime minister could safely meet in case Britain came under attack, explains Jonathan Asbury, author of Secrets of Churchill’s War Rooms. This detail came as a surprise to Asbury when he started working on a book, published earlier this year by the Imperial War Museums, which takes readers behind the glass panels of the storied space.

“I knew Churchill was the lead voice warning about the threat of German air power, but I hadn’t realized he’d been quite active in talking about the defenses against that,” says Asbury.

Secrets of Churchill's War Rooms

With Secrets of Churchill’s War Rooms, you can go behind the glass partitions that separate the War Rooms from the visiting public, closer than ever before to where Churchill not only ran the war—but won it. This magnificent volume offers up-close photography of details in every room and provides access to sights unavailable on a simple tour of Churchill War Rooms.

When Churchill first entered the political sphere in 1900, he had rapidly ascended the ranks of the British government. In the decades leading up to his time as prime minister, he had been appointed the president of Board of Trade, colonial secretary, first lord of the Admiralty, minister of munitions, war, and air, and chancellor of the exchequer. But the “British Bulldog” also sustained heavy political blows, some self-imposed, others at the hands of his rivals. By the 1930s, the public had soured on Churchill, especially his refusal to weaken Britain’s colonial grip on the Indian empire. They saw Churchill as equally out-of-touch as he railed against what he viewed as the rising German threat.

But Churchill saw what was coming, and he knew Britain was not prepared. In a private room at the House of Commons in 1936, he called on Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, who at the time was promoting a message of international disarmament, to take steps to defend Britain against the German air threat. “Have we organized and created an alternative center of government if London is thrown into confusion?” he asked.

“I don’t think you can say he was personally responsible for [the War Rooms] being created. Other people were thinking along the same lines, but he lead the pressure … to make sure it happened,” says Asbury.

It took two more years, after the Nazis had taken over Czechoslovakia and annexed Austria, for the idea of an emergency headquarters to be approved. Finally, in May, 1938, construction began in earnest to create a safe space to house the heads of the military; the structure became fully operational on August 27, 1939, one week before Britain and France declared war on Germany. Within the next year, Baldwin’s successor, Neville Chamberlain, resigned as prime minister, and Churchill found himself suddenly at the seat of British power. When he walked through his War Rooms for the first time as prime minister in 1940, the country was bracing itself for total war, and the Battle of Britain was just weeks away.

The subterranean rooms—spread out over two claustrophobic floors—allowed Churchill’s war cabinet, which included the heads of the army, navy and air force, to meet in a secure space, which became crucial after the German Luftwaffe launched the eight-month Blitz campaign in September. (Soon after the Blitz began, much to Churchill’s shock and horror, he learned that the bunker was not bomb-proof—an oversight quickly rectified with a generous new coating of concrete, explains Asbury.)

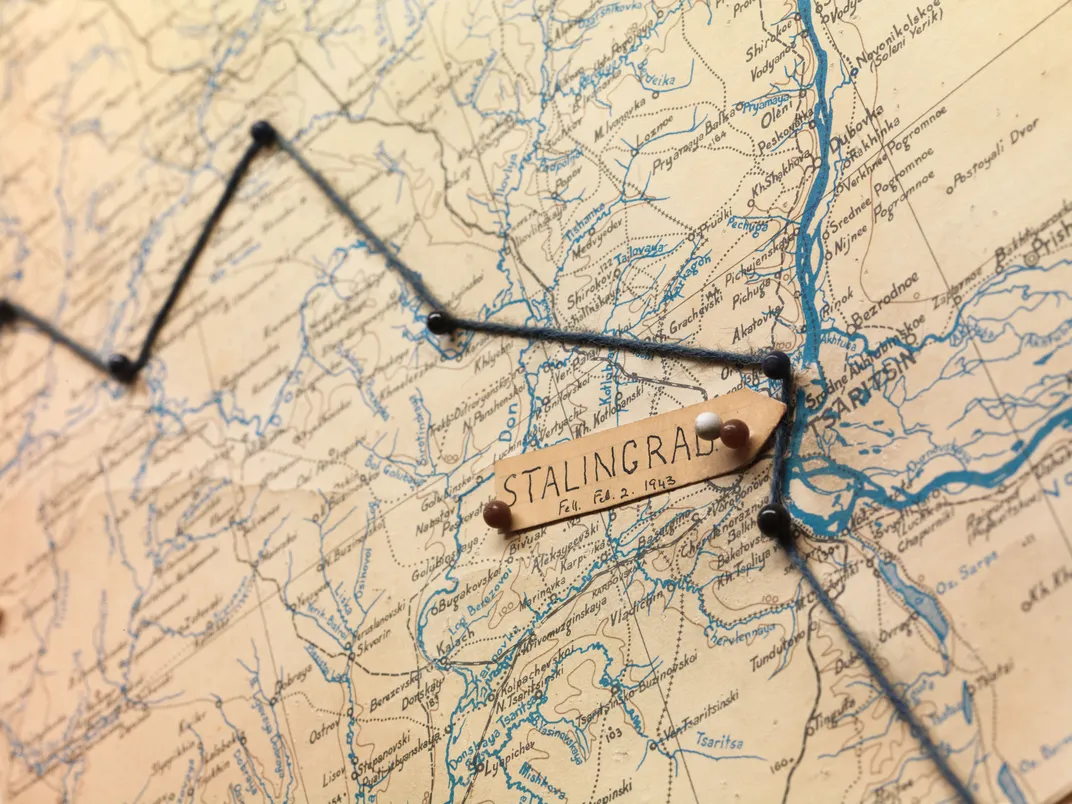

Churchill’s war cabinet met in the bunker 115 times during the course of the war, discussing everything from Dunkirk to the Battle of Britain to Stalingrad. The staff kept the bunker operational 24 hours a day, seven days a week, until August 16, 1945, two days after Japan publically announced its unconditional surrender. Only then did the lights in the Map Room Annex—where all of the intelligence came in to Churchill’s military advisers—turn off for the first time in six years.

According to Asbury, almost immediately after the war, a small stream of visitors were brought into the rooms for unofficial tours, even as government officials continued to toil away on secret Cold War projects in several of the rooms (with sensitive documents sometimes left out in the open). By the late 1940s, more official tours began to take place, and an effort to preserve the rooms (many of which had been significantly altered when they were put to new use after the war) began. Interest in the War Rooms steadily built until the Imperial War Museum was asked to take it over and open it up fully to the public in 1984. In the early 2000s, an expansion to the War Rooms opened up more of the original complex for view, in addition to adding a museum dedicated to Churchill.

But while anyone can tour the War Rooms for themselves today, what they can’t do is go behind the glass to see the artifacts in the detail that Asbury shares in his book.

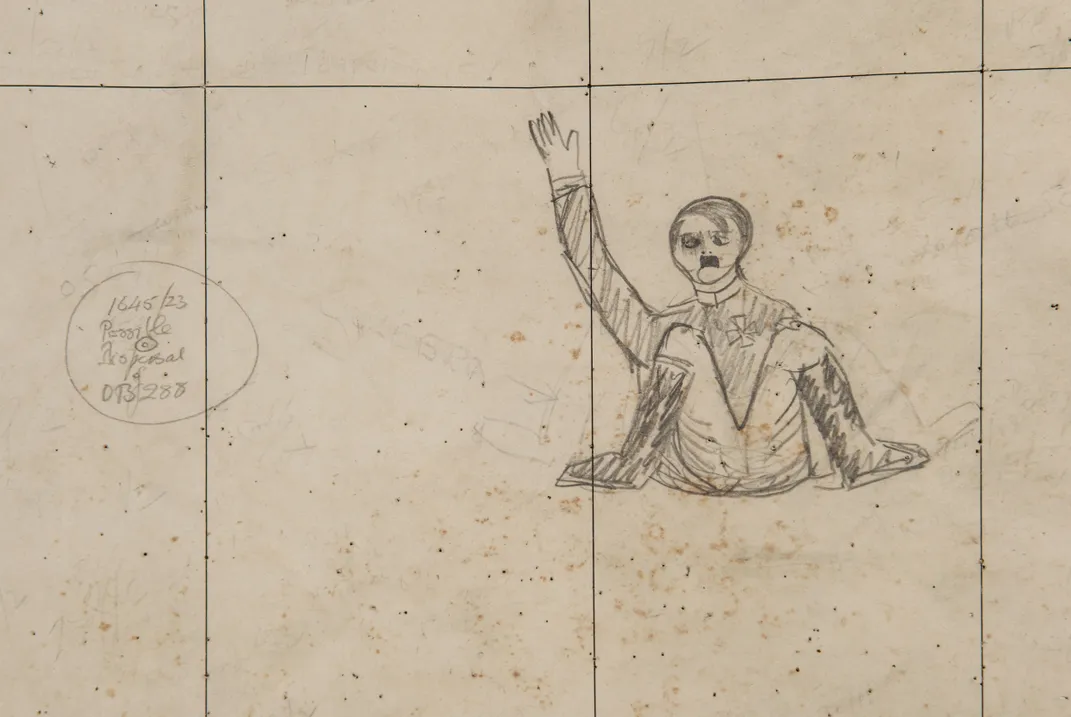

Paging through Secrets of Churchill’s War Rooms, what is striking about the underground bunker is the level of improvisation that went into its creation and evolution. The decision of which maps would go into the Map Room, for example, was just made by some government worker who was told that there was going to be a war room and that it would need maps. When he asked his commanding officer what maps he should acquire, “The guy just said, 'well, your guess is as good as mine,'” says Asbury.

The Map Room is arguably the most iconic room in the complex. A large map on the wall marked cargo ships movements across the Atlantic and the locations where the U-boats had sunk them. It became pockmarked so heavily that pieces of it had to be replaced as the war went on. The convoy map occupied much of Churchill’s fears, says Asbury. “He thought if one thing was going to defeat them, it would be if they couldn’t get enough supplies if Germany succeeded in its U-boat campaign. I’m sure he would have spent time staring at that map,” he says.

Asbury includes lighter accounts of the War Rooms as well, such as a recollection of a toilet paper roll, which papered the maze-like space for Christmas or a document marked “Operation Desperate,” written up by the woman who worked in the War Rooms, requesting stockings and cosmetics.

But more than anything, a close-up look at the War Rooms reveals the desperate situation that Britain faced. Rooms were equipped with gun racks so that officers could defend themselves if the War Rooms ever came under a parachute attack or invasion, and Asbury notes that Churchill’s bodyguard carried a loaded .45 Colt pistol for the prime minister, which he intended to use against the enemy and ultimately himself if the situation came down to it.

Asbury first visited the War Rooms after its latest overhaul with his oldest son George, who was just a baby at the time. He remembers feeling claustrophobic. “You feel like you’re quite a long way below ground even though you’re not actually very far,” he says. “I just got this real sense you feel very close to the [history]. It’s quite something to look at the rooms. That is the bed Churchill slept in, even if it was only four or five times. That is the desk he sat at.”

One of the most thrilling moments working on the book, he says, was getting to sink into Churchill’s chair in the Cabinet War Room. Churchill sat in that chair opposite the heads of the army, navy and air force, a setup seemingly designed for confrontation. Sitting in Churchill’s chair, Asbury gained new appreciation for the wartime leader.

“This incredibly powerful trio of men was sitting directly opposite of Churchill and they genuinely would argue,” he says. “One of Churchill’s great strengths was allowing himself to be challenged and pushing and pushing and pushing, but being prepared to concede when his experts argued back.”

The situation took an undeniable toll on Churchill, as a picture taken of one of the arms of Churchill’s chair reveals. Up close, the polished wood betrays marks from Churchill’s nails and signet ring. “They’re quite deep gouges,” says Asbury. “It makes you realize just how stressful it must have been.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.