What Led Benjamin Franklin to Live Estranged From His Wife for Nearly Two Decades?

A stunning new theory suggests that a debate over the failed treatment of their son’s smallpox was the culprit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/f9/53f9e9d8-ff1a-4164-a686-ce595ec2cad2/sep2017_h03_benfranklin-wr.jpg)

In October 1765, Deborah Franklin sent a gushing letter to her husband, who was in London on business for the Pennsylvania legislature. “I have been so happy as to receive several of your dear letters within these few days,” she began, adding that she had read one letter “over and over.” “I call it a husband’s Love letter,” she wrote, thrilled as though it were her first experience with anything of the kind.

Perhaps it was. Over 35 years of marriage, Benjamin Franklin had indirectly praised Deborah’s work ethic and common sense through “wife” characters in his Pennsylvania Gazette and Poor Richard’s Almanac. He had celebrated her faithfulness, compassion and competency as a housekeeper and hostess in a verse titled “I Sing My Plain Country Joan.” But he seems never to have written her an unabashed expression of romantic love. Whether the letter in question truly qualified as his first is unknown, since it has been lost. But it’s likely that Deborah exaggerated the letter’s romantic aspects because she wanted to believe her husband loved her and would return to her.

That February Franklin, newly arrived in London, had predicted that he would be home in “a few Months.” But now he had been gone for 11, with no word on when he would come back. Deborah could tell herself that a man who would write such a letter would not repeat his previous sojourn in England, which had begun in 1757 with a promise to be home soon and dragged on for five years, during which rumors filtered back to Philadelphia that he was enjoying the company of other women. (Franklin denied it, writing he would “do nothing unworthy the Character of an honest Man, and one that loves his Family.”) But as month after month passed with no word on Benjamin’s voyage home, it became clear that history was repeating itself.

This time Franklin would be gone for ten years, teasing his imminent return almost every spring or summer and then canceling at nearly the last minute and without explanation. Year after year Deborah stoically endured the snubbing, even after she had a stroke in early spring 1769. But as her health declined, she gave up her vow not to give him “one moment’s trouble.” “When will it be in your power to come home?” she asked in August 1770. A few months later she pressed him: “I hope you will not stay longer than this fall.”

He ignored her appeals until July 1771, when he wrote her: “I purpose it [his return] firmly after one Winter more here.” The following summer he canceled again. In March and April 1773 he wrote vaguely of coming home, and then in October he trotted out what had become his stock excuse, that winter passage was too dangerous. In February 1774, Benjamin wrote that he hoped to return home in May. In April and July he assured her he would sail shortly. But he never came. Deborah Franklin suffered another stroke on December 14, 1774, and died five days later.

We tend to idealize our founding fathers. So what should we make of Benjamin Franklin? One popular image is that he was a free and easy libertine—our founding playboy. But he was married for 44 years. Biographers and historians tend to shy away from his married life, perhaps because it defies idealization. John and Abigail Adams had a storybook union that spanned half a century. Benjamin and Deborah Franklin spent all but two of their final 17 years apart. Why?

The conventional wisdom is that their marriage was doomed from the beginning, by differences in intellect and ambition, and by its emphasis on practicality over love; Franklin was a genius and needed freedom from conventional constraints; Deborah’s fear of ocean travel kept her from joining her husband in England and made it inevitable that they would drift apart. Those things are true—up to a point. But staying away for a decade, dissembling year after year about his return, and then refusing to come home even when he knew his wife was declining and might soon die, suggests something beyond bored indifference.

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

In this colorful and intimate narrative, Isaacson provides the full sweep of Franklin’s amazing life, showing how he helped to forge the American national identity and why he has a particular resonance in the twenty-first century.

Franklin was a great man—scientist, publisher, political theorist, diplomat. But we can’t understand him fully without considering why he treated his wife so shabbily at the end of her life. The answer isn’t simple. But a close reading of Franklin’s letters and published works, and a re-examination of events surrounding his marriage, suggests a new and eerily resonant explanation. It involves their only son, a lethal disease and a disagreement over inoculation.

**********

As every reader of Franklin’s Autobiography knows, Deborah Read first laid eyes on Benjamin Franklin the day he arrived in Philadelphia, in October 1723, after running away from a printer’s apprenticeship with his brother in Boston. Fifteen-year-old Deborah, standing at the door of her family’s house on Market Street, laughed at the “awkward ridiculous Appearance” of the bedraggled 17-year-old stranger trudging down the street with a loaf of bread under each arm and his pockets bulging with socks and shirts. But a few weeks later, the stranger became a boarder in the Read home. After six months, he and the young woman were in love.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania’s governor, William Keith, happened upon a letter Franklin had written and decided he was “a young Man of promising Parts”—so promising that he offered to front the money for Franklin to set up his own printing house and promised to send plenty of work his way. Keith’s motives may have been more political than paternal, but with that, the couple “interchang’d some Promises,” in Franklin’s telling, and he set out for London. His intention was to buy a printing press and type and return as quickly as possible. It was November 1724.

Nothing went as planned. In London, Franklin discovered that the governor had lied to him. There was no money waiting, not for equipment, not even for his return passage. Stranded, he wrote Deborah a single letter, saying he would be away indefinitely. He would later admit that “by degrees” he forgot “my engagements with Miss Read.” In declaring this a “great Erratum” of his life, he took responsibility for Deborah’s ill-fated marriage to a potter named John Rogers.

But the facts are more complicated. Benjamin must have suspected that when Sarah Read, Deborah’s widowed mother, learned that he had neither a press nor guaranteed work, she would seek another suitor for her daughter. Mrs. Read did precisely that, later admitting to Franklin, as he wrote, that she had “persuaded the other Match in my Absence.” She had been quick about it, too; Franklin’s letter reached Deborah in late spring 1725, and she was married by late summer. Benjamin, too, had been jilted.

Just weeks into Deborah’s marriage, word reached Philadelphia that Rogers had another wife in England. Deborah left him and moved back in with her mother. Rogers squandered Deborah’s dowry and racked up big debts before disappearing. And yet she remained legally married to him; a woman could “self-divorce,” as Deborah had done in returning to her mother’s home, but she could not remarry with church sanction. At some point she was told that Rogers had died in the West Indies, but proving his death—which would have freed Deborah to remarry formally—was impractically expensive and a long shot besides.

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in October 1726. In the Autobiography he wrote that he “should have been...asham’d at seeing Miss Read, had not her Friends...persuaded her to marry another.” If he wasn’t ashamed, what was he? In classic Franklin fashion, he doesn’t say. Possibly he was relieved. But it seems likely, given his understanding that Deborah and her mother had quickly thrown him over, that he felt at least a tinge of resentment. At the same time, he also “pity’d” Deborah’s “unfortunate Situation.” He noted that she was “generally dejected, seldom cheerful, and avoided Company,” presumably including his. If he still had feelings for her, he also knew that her dowry was gone and she was, technically, unmarriageable.

He, meanwhile, became more eligible by the year. In June 1728, he launched a printing house with a partner, Hugh Meredith. A year later he bought the town’s second newspaper operation, renamed and reworked it, and began making a success of the Pennsylvania Gazette. In 1730 he and Meredith were named Pennsylvania’s official printers. It seemed that whenever he decided to settle down, Franklin would have his pick of a wife.

Then he had his own romantic calamity: He learned that a young woman of his acquaintance was pregnant with his child. Franklin agreed to take custody of the baby—a gesture as admirable as it was uncommon—but that decision made his need for a wife urgent and finding one problematic. (Who that woman was and why he couldn’t or wouldn’t marry her remain mysteries to this day.) No desirable young woman with a dowry would want to marry a man with a bastard infant son.

But Deborah Read Rogers would.

Thus, as Franklin later wrote, the former couple’s “mutual Affection was revived,” and they were joined in a common-law marriage on September 1, 1730. There was no ceremony. Deborah simply moved into Franklin’s home and printing house at what is now 139 Market Street. Soon she took in the infant son her new husband had fathered with another woman and began running a small stationery store on the first floor.

Benjamin accepted the form and function of married life—even writing about it (skeptically) in his newspaper—but kept his wife at arm’s length. His attitude was reflected in his “Rules and Maxims for Promoting Matrimonial Happiness,” which he published a month after he and Deborah began living together. “Avoid, both before and after marriage, all thoughts of managing your husband,” he advised wives. “Never endeavor to deceive or impose on his understanding: nor give him uneasiness (as some do very foolishly) to try his temper; but treat him always beforehand with sincerity, afterwards with affection and respect.”

Whether at this point he loved Deborah is difficult to say; despite his reputation as a flirt and a charmer, he seldom made himself emotionally available to anyone. Deborah’s famous temper might be traced to her frustration with him, as well as the general unfairness of her situation. (Franklin immortalized his wife’s fiery personality in various fictional counterparts, including Bridget Saunders, wife of Poor Richard. But there are plenty of real-life anecdotes as well. A visitor to the Franklin home in 1755 saw Deborah throw herself to the floor in a fit of pique; he later wrote that she could produce “invectives in the foulest terms I ever heard from a gentlewoman.”) But her correspondence leaves no doubt that she loved Benjamin and always would. “How I long to see you,” she wrote to him in 1770, after 40 years of marriage and five years into his second trip to London. “If you’re Having the gout...I wish I was near enough to rub it with a light hand.”

Deborah Franklin wanted a real marriage. And when she became pregnant with their first child, near the beginning of 1732, she had reason to hope she might have one. Her husband was thrilled. “A ship under sail and a big-bellied Woman, / Are the handsomest two things that can be seen common,” Benjamin would write in June 1735. He had never been much interested in children, but after the birth of Francis Folger Franklin, on October 20, 1732, he wrote that they were “the most delightful Cares in the World.” The boy, whom he and Deborah nicknamed “Franky,” gave rise to a more ebullient version of Franklin than he had allowed the world to see. He also became more empathetic—it’s hard to imagine he would have written an essay like “On the Death of Infants,” which was inspired by the death of an acquaintance’s child, had he not been enraptured by his own son and fearful lest a similar fate should befall him.

By 1736, Franklin had entered the most fulfilling period of his life so far. His love for Franky had brought him closer to Deborah. Franklin had endured sadness—the death of his brother James, the man who had taught him printing and with whom he had only recently reconciled—and a serious health scare, his second serious attack of pleurisy. But he had survived, and at age 30 was, as his biographer J.A. Leo Lemay pointed out, better off financially and socially than any of his siblings “and almost all of Philadelphia’s artisans.” That fall, the Pennsylvania Assembly appointed him its clerk, which put him on the inside of the colony’s politics for the first time.

That September 29, a contingent of Indian chiefs representing the Six Nations was heading for Philadelphia to renegotiate a treaty when government officials halted them a few miles short of their destination and advised them to go no farther. The legislature’s minutes, delivered to Franklin for printing, spelled out the reason: Smallpox had broken out “in the heart or near the middle of the town.”

**********

Smallpox was the most feared “distemper” in Colonial America. No one yet understood that it spread when people inhaled an invisible virus. The disease was fatal in more than 30 percent of all cases and even more deadly to children. Survivors were often blind, physically or mentally disabled and horribly disfigured.

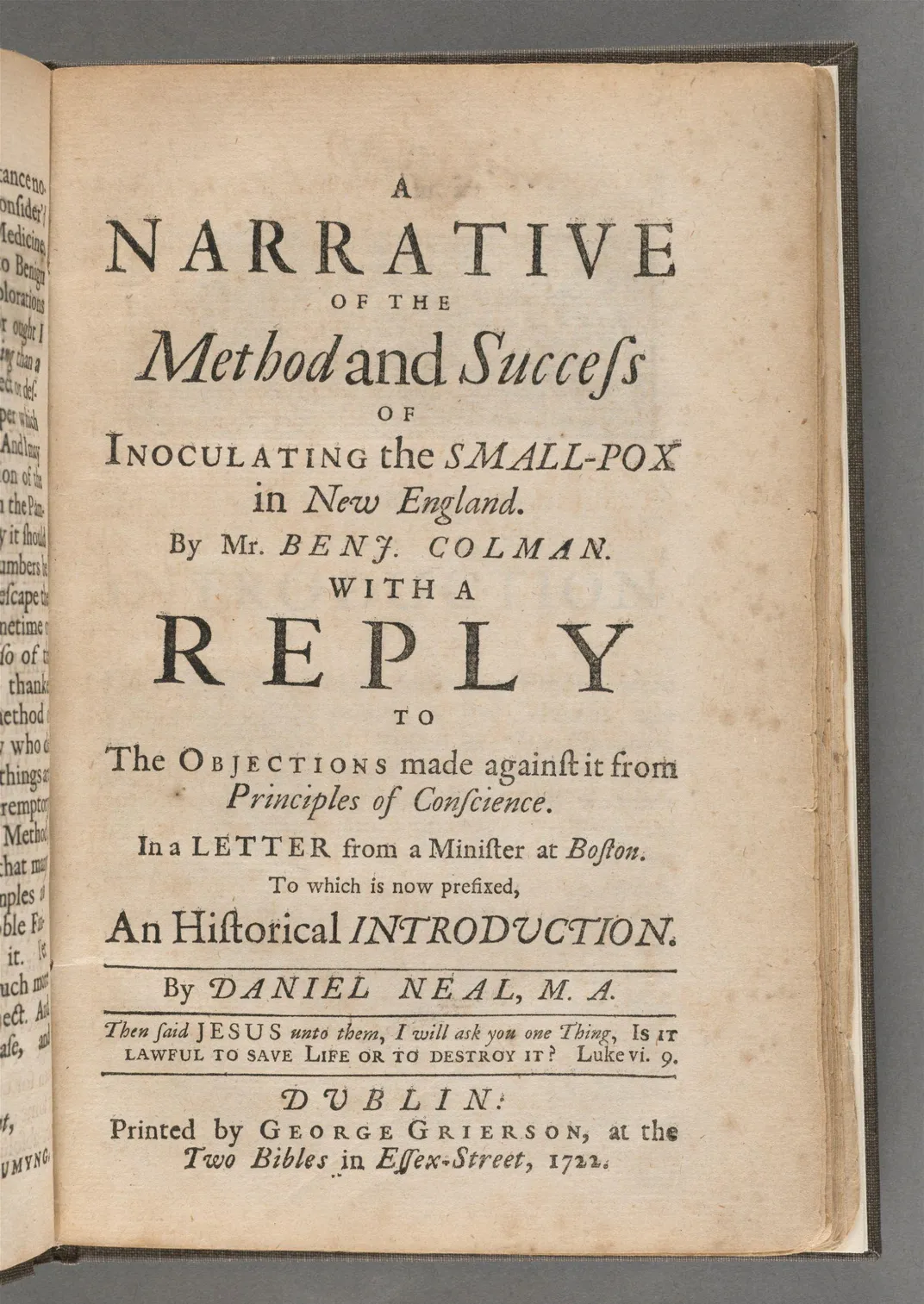

In 1730, Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette had reported extensively on an outbreak in Boston. But rather than focusing on the devastation caused by the disease, Franklin’s coverage dealt primarily with the success of smallpox inoculation.

The procedure was a precursor to modern-day vaccination. A doctor used a scalpel and a quill to take fluid from smallpox vesicles on the skin of a person in the throes of the disease. He deposited this material in a vial and brought it to the home of the person to be inoculated. There he made a shallow incision in the patient’s arm and deposited material from the vial. Usually, inoculated patients became slightly ill, broke out in a few, smallish pox, and recovered quickly, immune to the disease for the rest of their lives. Occasionally, however, they developed full-blown smallpox or other complications and died.

Franklin’s enthusiasm for smallpox inoculation dated to 1721, when he was a printer’s apprentice to James in Boston. An outbreak in the city that year led to the first widespread inoculation trial in Western medicine—and bitter controversy. Supporters claimed that inoculation was a blessing from God, opponents that it was a curse—reckless, impious and tantamount to attempted murder. Franklin had been obliged to help print attacks against it in his brother’s newspaper, but the procedure’s success won him over. In 1730, when Boston had another outbreak, he used his own newspaper to promote inoculation in Philadelphia because he suspected the disease would spread south.

The Gazette reported that of the “Several Hundreds” of people inoculated in the Boston area that year, “about four” had died. Even with those deaths—which doctors attributed to smallpox contracted before inoculation—the inoculation death rate was negligible compared with the fatality rate from naturally acquired smallpox. Two weeks after that report, the Gazette reprinted a detailed description of the procedure from the authoritative Chambers’s Cyclopaedia.

And when, in February 1731, Philadelphians began coming down with smallpox, Franklin’s backing became even more urgent. “The Practice of Inoculation for the Small-Pox, begins to grow among us,” he wrote the next month, adding that “the first Patient of Note,” a man named “J. Growdon, Esq,” had been inoculated without incident. He was reporting this, he said, “to show how groundless all those extravagant Reports are, that have been spread through the Province to the contrary.” In the next week’s Gazette he plugged inoculation again, excerpting a prominent English scientific journal. By the time the Philadelphia epidemic ended that July, 288 people were dead, but that total included only one of the approximately 50 people who had been inoculated.

Whether Franklin himself was inoculated or survived a case of naturally acquired smallpox at some point is unknown—there’s no evidence on record. But he emerged as one of the most outspoken inoculation advocates in the Colonies. When smallpox returned to Philadelphia in September 1736, he couldn’t resist lampooning the logic of the English minister Edmund Massey, who had famously declared inoculation the Devil’s work, citing Job 2:7: “So went Satan forth from the presence of the Lord and smote Job with sore boils from the sole of the foot unto his crown.” Near the front of the new Poor Richard’s Almanac, which he was preparing to print, Franklin countered:

God offer’d to the Jews salvation;

And ‘twas refus’d by half the nation:

Thus (tho ‘tis life’s great preservation),

Many oppose inoculation.

We’re told by one of the black robe,

The devil inoculated Job:

Suppose ‘tis true, what he does tell;

Pray, neighbours, did not Job do well?

Significantly, this verse was Franklin’s only comment on smallpox or inoculation through the first four months of the new outbreak. Not until December 30 did he break his silence, in a stunning 137-word note at the end of that week’s Gazette. “Understanding ’tis a current Report,” it began, “that my Son Francis, who died lately of the Small Pox, had it by Inoculation....”

Franky had died on November 21, a month after his 4th birthday, and his father sought to dispel the rumor that a smallpox inoculation was responsible. “Inasmuch as some People are...deter’d from having that Operation perform’d on their Children, I do hereby sincerely declare, that he was not inoculated, but receiv’d the Distemper in the common Way of Infection,” he wrote. He had “intended to have my Child inoculated, as soon as he should have recovered sufficient Strength from a Flux with which he had been long afflicted.”

**********

Many years later, Franklin admitted in a letter to his sister Jane that Franky’s death devastated him. And we can imagine that for Deborah it was even worse. Perhaps out of compassion, few of Franklin’s contemporaries questioned his explanation for not inoculating Franky or asked why he had gone so quiet on the procedure in the months before his son died. Many biographers and historians have followed suit, accepting at face value that Franky was simply too sick for inoculation. Lemay, one of Franklin’s best biographers, is representative. He wrote that Franklin fully intended to inoculate the boy, but that Franky’s sickness dragged on and “smallpox took him before his recovery.” Indeed, Lemay went even further in providing cover for Franklin, describing Franky as a “sickly infant” and a “sickly child.” This, too, has become accepted wisdom. But Franklin himself hinted that something else delayed his action and perhaps cost Franky his life. Most likely, it was a disagreement with Deborah over inoculation.

The argument that Franky was sickly is based primarily on one fact: Nearly a year passed between his birth and his baptism. More substantive evidence suggests the delay was due to Franklin’s oft-expressed antipathy to organized religion. When Franky was finally baptized, his father just happened to be on an extended trip to New England. It appears that Deborah, tired of arguing with her husband over the need to baptize their son, had it done while he was out of town.

As to Franky’s general health, the best evidence is in Franklin’s 1733 piece in the Gazette celebrating a scolding wife. If Deborah was the model for this fictional wife, as she seems to have been, it’s worth noting the author’s rationale for preferring her type. Such women, he wrote, have “sound and healthy Constitutions, produce vigorous Offspring, are active in the Business of the Family, special good Housewives, and very Careful of their Husbands Interest.” It’s unlikely that he would have included “produce vigorous Offspring” if his son, then 9 months old, had been sickly.

So Franky probably wasn’t a particularly sickly child. But he might have had, as Franklin claimed, an unfortunately timed (and uncommonly drawn-out) case of dysentery throughout September, October and early November 1736. This was the “flux” that Franklin’s editor’s note referred to. Did it render the boy too sick to be inoculated?

From the outset, his father hinted otherwise. Franklin never said his son was sick, but that he “had not recovered sufficient Strength.” It’s possible that Franky had been ill, but was no longer showing symptoms of dysentery. This would mean that, contrary to what some biographers and historians have assumed, Franky’s inoculation was not out of the question. Franklin said as much many years later. Addressing Franky’s death in the Autobiography, he wrote: “I long regretted bitterly & still regret that I had not given it [smallpox] to him by Inoculation.” If he regretted not being able to give his son smallpox by inoculation, he would have said so. Clearly Franklin believed he had had a choice and had chosen wrong.

How did a man who understood better than most the relative safety and efficacy of inoculation choose wrong? Possibly he just lost his nerve. Other men had. In 1721 Cotton Mather—the man who had stumbled upon the idea of inoculation and then pushed it on the doctors of Boston, declaring it infallible—had stalled for two weeks before approving his teenage son’s inoculation, knowing all the while that Sammy Mather’s Harvard roommate was sick with smallpox.

It’s more likely, though, that Benjamin and Deborah disagreed over inoculation for their son. Franky was still Deborah’s only child (the Franklins’ daughter, Sarah, would not be born for seven more years) and the legitimizing force in her common-law marriage. Six years into that marriage, her husband was advancing so quickly in the world that she might have begun to worry he might one day outgrow his plain, poorly educated wife. If originally she had believed Franky would bring her closer to Benjamin, now she just hoped the boy would help her keep hold of him. By that logic, risking her son to inoculation was unacceptable.

That scenario—parents unable to agree on inoculation for their child—was precisely the one Ben Franklin fixed on two decades after his son’s death, when he wrote about impediments to the procedure’s public acceptance. If “one parent or near relation is against it,” he noted in 1759, “the other does not chuse to inoculate a child without free consent of all parties, lest in case of a disastrous event, perpetual blame should follow.” He raised that dilemma again in 1788. After expressing his regret over having failed to inoculate Franky, he added: “This I mention for the Sake of Parents, who omit that Operation on the Supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a Child died under it; my Example showing that the Regret may be the same either way, and that therefore the safer should be chosen.”

Franklin took the blame for not inoculating Franky, just as he took the blame for Deborah’s disastrous first marriage. But as in that earlier case, his public chivalry probably disguised his private beliefs. Whether he blamed Deborah, or blamed himself for listening to her, the hard feelings relating to the death of their beloved son—“the DELIGHT of all that knew him,” according to the epitaph on his gravestone—appear to have ravaged their relationship. What followed was nearly 40 years of what Franklin referred to as “perpetual blame.”

**********

It surfaced in various forms. A recurring theme was Benjamin’s belief that Deborah was irresponsible. In August 1737, less than a year after Franky’s death, he lashed out at her for mishandling a sale in their store. A customer had bought paper on credit, and Deborah had forgotten to note which paper he had bought. Theoretically, the customer could claim to have purchased a lesser grade and underpay what he owed. It was a small matter, but Benjamin was incensed. Deborah’s shocked indignation is apparent in the entry she subsequently made in the shop book, in the place where she should have entered the details about the paper stock. Paraphrasing her husband, she wrote: “A Quier of paper that my careless wife forgot to set down and now the careless thing don’t know the prices so I must trust you.”

Benjamin also conspicuously overlooked, or even denigrated, Deborah’s fitness as a mother. His 1742 ballad in praise of her, as Lemay points out, touched upon every aspect of her domestic skills except motherhood—even though she had mothered William Franklin since infancy and, shortly after Franky’s death, had taken in young James Franklin Jr., the son of Ben’s deceased brother. And when Franklin sailed for London in 1757 he made no secret of his ambivalence about leaving his 14-year-old daughter with Deborah. After insisting that he was leaving home “more cheerfully” for his confidence in Deborah’s ability to manage his affairs and Sarah’s education, he added: “And yet I cannot forbear once more recommending her to you with a Father’s tenderest Concern.”

**********

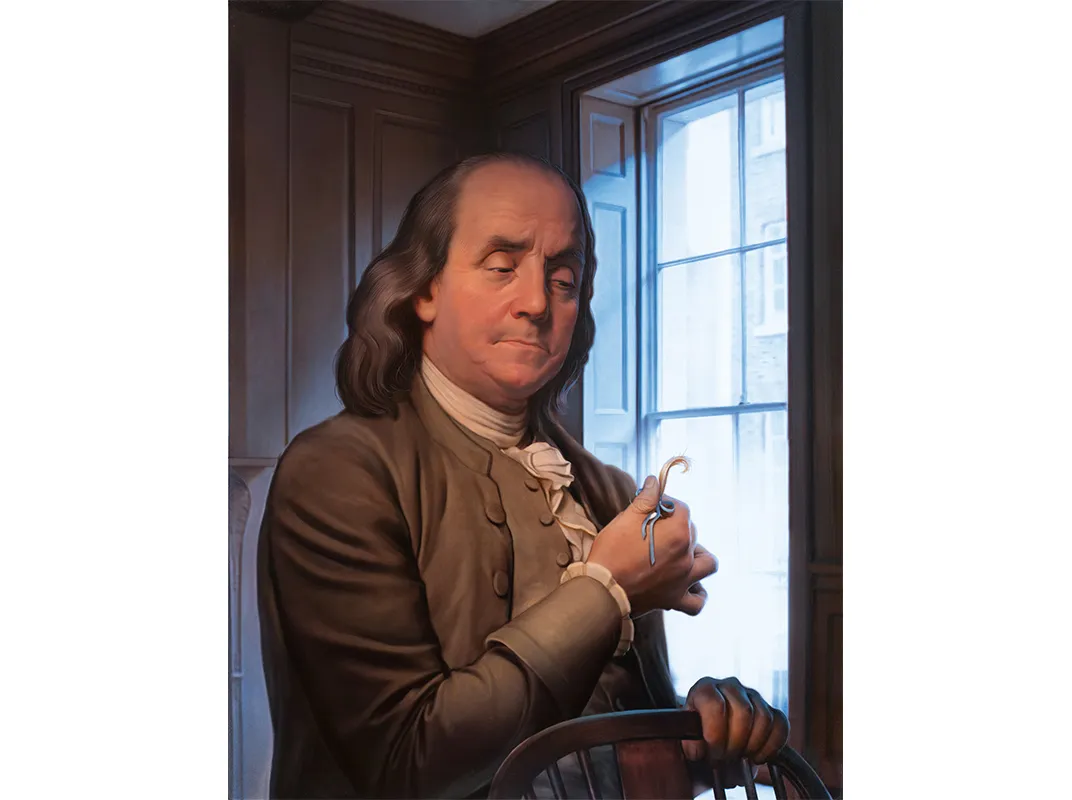

At some point in the year after Franky died, Benjamin commissioned a portrait of the boy. Was it an attempt to lift Deborah out of debilitating grief? Given Franklin’s notorious frugality, the commission was an extraordinary indulgence—most tradesmen didn’t have portraits made of themselves, let alone their children. In a sense, though, this was Franklin’s portrait, too: With no likeness of Franky to work from, the artist had Benjamin sit for it.

The final product—which shows Franklin’s adult face atop a boy’s body—is disconcerting, but also moving. Deborah appears to have embraced it without qualm—and over time seems to have accepted it as a surrogate for her son. In 1758, near the start of Franklin’s first extended stay in London, she sent the portrait or a copy of it to him, perhaps hoping it would bind him to her in the same way she imagined its subject once had.

Returned to Philadelphia, the painting took on a nearly magical significance a decade later, when family members noticed an uncanny resemblance between Sarah Franklin’s 1-year-old son, Benjamin Franklin Bache, and the Franky of the portrait. In a June 1770 letter, an elated Deborah wrote to her husband that William Franklin believed Benny Bache “is like Frankey Folger. I thought so too.” “Everyone,” she wrote, “thinks as much as though it had been drawn for him.” For the better part of the next two years Deborah’s letters to Benjamin focused on the health, charm and virtues of the grandson who resembled her dead son. Either intentionally or accidentally, as a side effect of her stroke, she sometimes confused the two, referring to Franklin’s grandson as “your son” and “our child.”

Franklin’s initial reply, in June 1770, was detached, even dismissive: “I rejoice much in the Pleasure you appear to take in him. It must be of Use to your Health, the having such an Amusement.” At times he seemed impatient with Deborah: “I am glad your little Grandson recovered so soon of his Illness, as I see you are quite in Love with him, and your Happiness wrapt up in his; since your whole long Letter is made up of the History of his pretty Actions.” Did he resent the way she had anointed Benny the new Franky? Did he envy it?

Or did he fear that they would lose this new Franky, too? In May 1771, on a kinder note, he wrote: “I am much pleased with the little Histories you give me of your fine Boy....I hope he will be spared, and continue the same Pleasure and Comfort to you, and that I shall ere long partake with you in it.”

Over time, Benjamin, too, came to regard the grandson he had yet to lay eyes on as a kind of reincarnation of his dead son. In a January 1772 letter to his sister Jane, he shared the emotions the boy stirred in him—emotions he had hidden from his wife. “All, who have seen my Grandson, agree with you in their accounts of his being an uncommonly fine Boy,” he wrote, “which brings often afresh to my Mind the Idea of my son Franky, tho’ now dead 36 Years, whom I have seldom seen equal’d in every thing, and whom to this Day I cannot think of without a Sigh.”

Franklin finally left London for home three months after Deborah died. When he met his grandson he, too, became infatuated with the boy—so much so that he effectively claimed Benny for his own. In 1776 he insisted that the 7-year-old accompany him on his diplomatic mission to France. Franklin didn’t return Benny Bache to his parents for nine years.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.