‘Better Babies’ Contests Pushed for Much-Needed Infant Health but Also Played Into the Eugenics Movement

Contests around the country judged infants like they would livestock as a motivator for parents to take better care of their children

:focal(756x1290:757x1291)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/b5/acb54b7f-5d1f-4ea5-9d00-a07868b10687/gettyimages-576821334.jpg)

Imagine going to the state fair and being sized up and given a grade based on a litany of bodily measurements, each carefully scrutinized by a room of experts—just like the cattle, pigs or sheep in the next building over. And it wasn’t just the circumference of your head or the presence of “offensive breath” that mattered. The judges looked at wildly subjective measures, too: Are you a liar? Jealous? Prone to worry and self-pity? At the end, you got a score that showed your overall values, and, if you performed well enough, maybe a trophy or medal to prove it.

These human contests started out by focusing on babies and young children, but soon entire families would also be judged at fairs for their lineage and cumulative flawlessness. The contests initially sought to amuse and promote wellness, but from their inception, they also lent popular exposure to the study of eugenics, which, in the early part of the 20th century, became increasingly acceptable as an enlightened science.

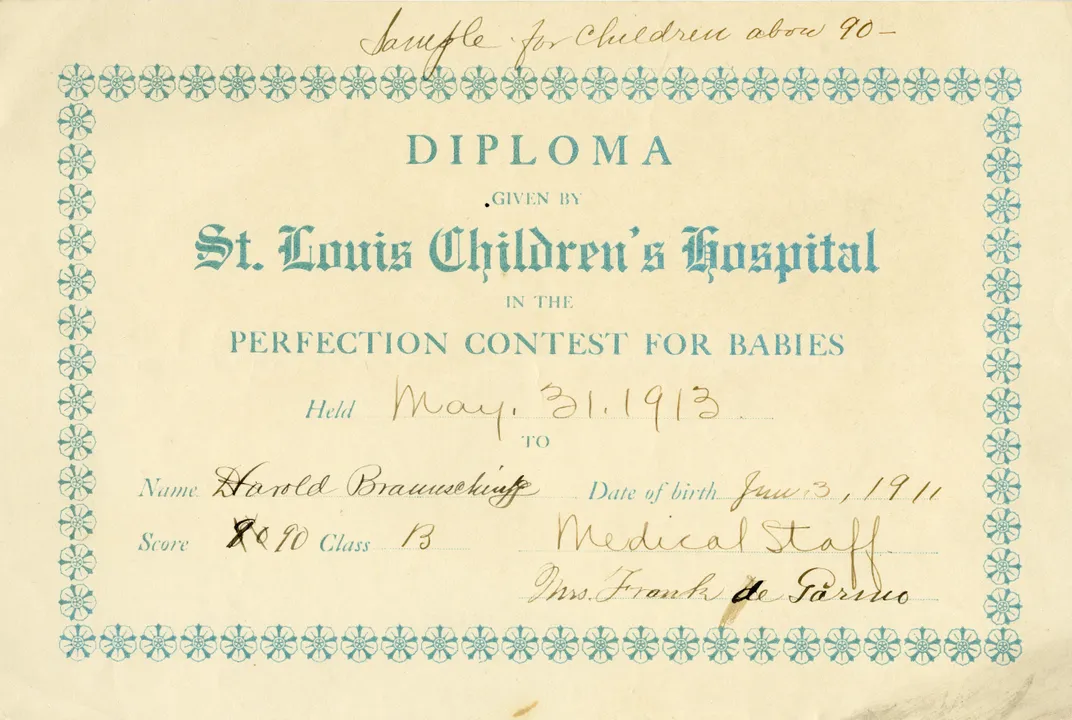

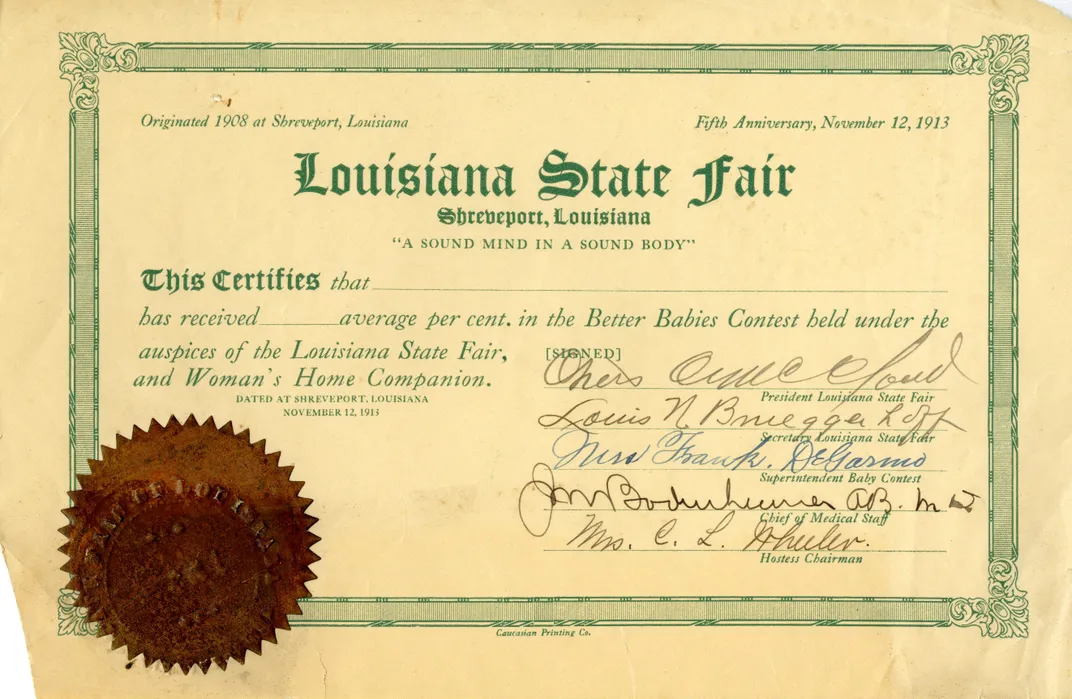

The 1908 Louisiana State Fair was the first to usher in this new kind of exhibit. Onlookers filed through to look at the menagerie of infants. Measurements were dutifully recorded by nurses in crisp, white caps, and winners were awarded silver trophies. The contest was organized by Mary DeGarmo, already a known advocate for children’s issues in the state when she enlisted the help of a local doctor to create a matrix to judge the most “scientific” baby. Being a winner meant being healthy, strong, and, implicitly, white; an embodiment of what the ideal American family could produce. As DeGarmo later wrote, “Much interest was shown as to the ‘Blood Will Tell’ theory. IT DID TELL.” The contest was soon emulated in the Midwest, gaining prominence and stature under the banner of baby betterment.

DeGarmo’s success caught the attention of a national magazine, the Woman’s Home Companion, which created its own standardized—and very thorough—scorecard and formed the Better Babies bureau to encourage community groups to hold their own contests. In 1913, the WHC spotlit Degarmo’s efforts in Louisiana, because “underneath the inviting charm of the idea is a serious scientific purpose—healthy babies, standardized babies, and always, year after year, Better Babies.”

The magazine routinely exhorted mothers across the nation to ensure their own babies reached their full potential by blending domestic responsibilities with nascent civic participation through women-founded, child-focused organizations that lobbied for social change. “We make the contest a social event because we want to know these mothers of little children and draw them into our organization, the Congress of Mothers,” Degarmo told the WHC, “and so, you see, science, social life and sentiment mingle in the Better Babies Movement as the Southern woman sees it.”

The contests grew in popularity at a time when there was, in fact, a dire and real need for greater awareness of child health. In the early 20th century, approximately 100 infants of every 1000 live births died before their first birthday, according to the CDC. Campaigns underscored the need for better hygiene, adequate nutrition and routine medical evaluations. The federal government also took notice of the needs of children—in 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt hosted a conference on the Care of Dependent Children. Out of that came the Children’s Bureau, founded in 1912, which helped address a wide range of ills affecting child welfare, from labor to infant mortality.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/02/db028357-30f3-4c16-971c-2858ed459b97/ms1879_001_front.jpg)

It was in this societal climate that Better Babies contests spread across the country through a diffuse network of organizations and sponsors. While emphasizing the need for improvements in the health and hygiene sphere, discussions around what constituted “better babies” were intertwined with the tenets of the eugenics movement.

Certain races—and physical and mental differences—were excluded entirely from this debate. Many eugenicists sought to encourage reproduction by what was deemed the most desirable, healthy, strong members of society and to weed out those deemed “feeble-minded” or otherwise less viable. The concept was hardly fringe—even President Roosevelt, in a letter to Charles Davenport, the director of the Eugenics Record Office, lamented a society which “permits unlimited breeding from the worst stocks.”

DeGarmo wrote of “child hygiene resulting from proper inheritance, as well as food and clothing and environment.” The two could work in a complementary fashion. “That’s one of the interesting things about the better babies contest is that there is a coexistence of both a focus on heredity and a focus on nurture,” says Alexandra Minna Stern, professor of history at the University of Michigan and author of Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America. Accoding to Stern, that balance, “legitimized their work and the well-child care the reformers and physicians are interested in. They want to support the idea that these are better babies, but they can also become better, and they can become better through having access to more nutritious food, to better mothering strategies, to a good interactive environment and things like that.”

The success of the Better Babies movement was not lost on eugenicists. Organizations like the Eugenics Record Office sought new data to feed into their extensive research projects. These contests could both promulgate these ideas in the public sphere and serve as a means to collect more records, more data.

“It’s a strategic move—they understand the popularity of these contests,” says Laura L. Lovett, professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and author of Conceiving the Future: Pronatalism, Reproduction and the Family in the United States, 1890-1938. As images of healthy babies popped up in newspapers around the country, “they realize you can popularize eugenics and ideas about inheritance by building on this model.”

Working with eugenicists conferred a certain credibility for advocates like DeGarmo because many viewed eugenics as the epitome of scientific progress. “If you were educated in any of the fields that touch on science, you’re probably at some level going to be identifying as a eugenicist at that time in 1900, 1908,” says Lovett. In the relatively new sphere of public health, “[Better Babies advocates] could legitimize themselves by upholding what is the most modern science and showing that they were able to master the language of heredity and understand its implications for child development,” says Stern.

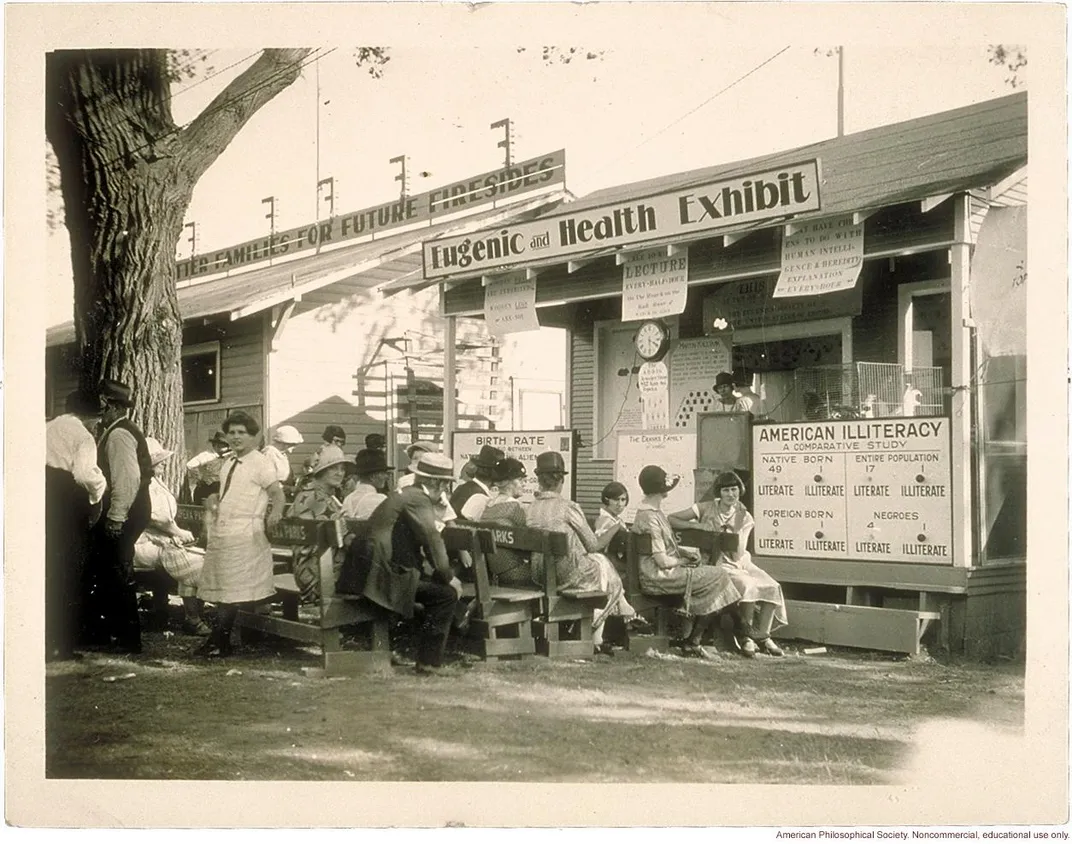

Judgment of individual babies soon morphed into a more eugenically driven evaluation of a gene pool in the form of “Fitter Families for Future Firesides,” which debuted in Kansas in 1920 under the guidance of Florence Sherbon and Mary T. Watts, organizers of a previous baby contest at the Iowa State Fair. While both contests may have reflected elements of eugenicist thinking, the primary emphasis shifted from factors mothers could control to heredity: Fitter Families took an approach based much more on lineage and what constituted a desirable type of family.

The contests were welcomed as progress in the understanding of human genes. A wire story in Kansas newspapers hailed Fitter Families as a step up from “old-fashioned” baby shows that would “go a step farther than the baby clinics do, by recording eugenic history of the entrants.”

They were also seen as long overdue when compared to the significant scientific advances made in livestock breeding. The Emporia Gazette touted the 1924 Kansas Free Fair contest for seeking “to apply the well-known principles of heredity and scientific care which have revolutionized agriculture and stock-breeding in the next higher order of creation – the human family.”

This new knowledge, proponents theorized, could be transferred, such that focusing on heredity would greatly benefit society if it were at last applied to humans. Watts told the Dearborn Independent that farmers had “started to improve their live stock by better housing and more careful feeding, but they still raised scrubs. It was not until they discovered that heredity was a factor in stock improvement that any great change in the grade of live stock took place.” The newspaper concluded that “the people of this progressive state no longer are content to breed only better animals. They are setting out to raise better citizens: to apply to the human race, some of the principles of heredity which have worked wonders in live stock improvement.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/17/4717327f-8dce-4738-8276-15a47c7bd291/010d-mendel-s-theatre-showing-inheritance-of-hair-color-demonstrated-by-leon-fradley-whitney.jpg)

The Fitter Families contests, like the Better Babies, soon spread to fairs across the country. Eugenics booths were set up to welcome fairgoers to learn and apply its lessons—and to provide broad-ranging information on their health. The exhibits even provided advice on the best marital matches to perpetuate desirable traits.

While seemingly benign, contests like these reinforced the notion of white Americans having the most desirable characteristics, and implicitly discouraged the inclusion of people who fell outside of that range. By setting scorecards and standards, the contest organizers put forth a hierarchy of humans. As the Pensacola Journal explained in 1913, in these types of contests “A physician scores a baby in precisely the same way as a judge of experience in live stock scores cattle, horses and hogs, and a gem expert scores diamonds. It is first necessary to establish a standard and then to compare each entry or specimen with what is known as a one-hundred percent, or perfect, product.”

Public acceptance of these concepts would also help pave way for national-level changes during the height of eugenics’ popularity in the 1920s. The sweeping Immigration Act of 1924 sharply restricted the number of foreigners who could enter the United States— “America must remain American,” as President Calvin Coolidge said during the signing ceremony. In 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the principle of sterilization of certain “defective persons” by the state. Both changes helped ensconce the tenets of eugenics in the mainstream and reduced the need for popular campaigning efforts. “In a way they’ve become institutionalized…so how important is it to do all this popularization when the kind of policies that they wanted become the status quo and remain the status quo until the 1960s or so,” says Stern.

The term eugenics itself would be marred when the horrors inflicted by Nazi Germany in the name of supposed racial purity became known to the American public, but the changes brought by the movement would be slow to fade. The idea of the “perfect” American family remained deeply ingrained, even in the absence of trophies. The arbiters of better babies and fitter families helped cement the role of both heredity and environment in quantifying superiority, ultimately helping to lay the groundwork for a more sinister school of thought taking hold in the American popular imagination.