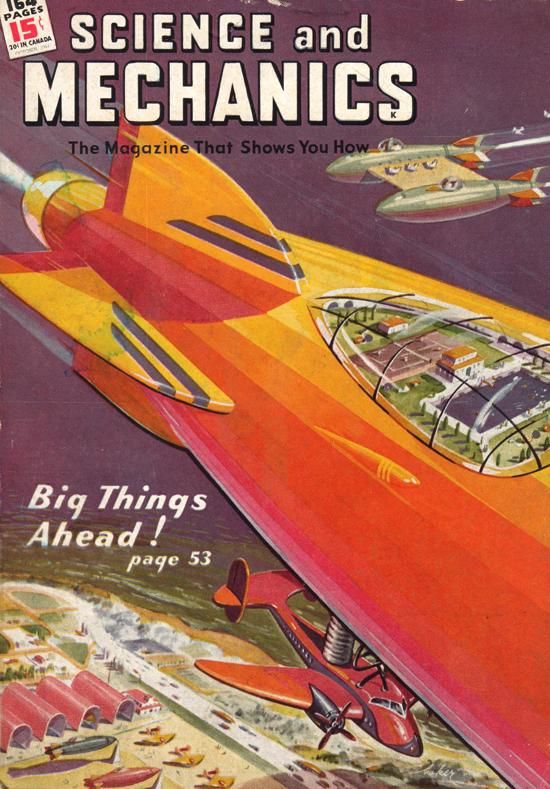

Big Things Ahead… But Keep Your Shirt On

Americans in the 1940s had wondrous expectations about the post-war world. Meet one author who advised them to curb their enthusiasm

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1944-science-and-mech-helicopter.jpg)

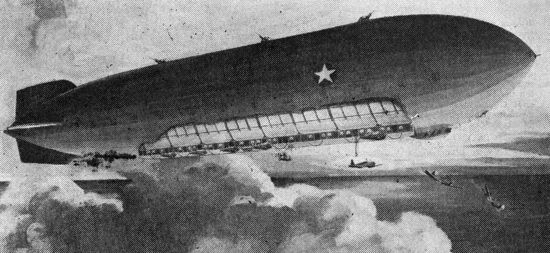

The October 1944 issue of Science and Mechanics looked at what technological advancements Americans might expect after WWII with an article titled, “Big Things Ahead — But Keep Your Shirt On,” by John Silence.

What makes this article so fascinating is that it looks at the advances of the future with optimism, but tempers that rosey outlook with realistic predictions. There were a number of stories in the early 1940s offering American readers a vision of the future after the war, but this is one of the few that asks people to keep their expectations in check. The article opens with the common assumptions of the day about the futuristic post-war world Americans would be living in:

Many of us have the idea that when Johnny comes marching home to his post-war world, he won’t know the old place. He’ll zing in on some contraption just short of the fourth dimension, and before he can zip himself out of his uniform and into his civvies, the walls of his pre-fabricated house will glow with electronic heat or his brow will be cooled by costless air conditioning.

The freezer in the basement will yield a perfect sirloin steak that the radio oven will broil to his favorite turn in something under 10 seconds, and while they’re bringing it in on an electric-plastic tray that keeps it hot, the dehydrated mush is being turned back into honest potatoes. And so on.

The piece then warns that you shouldn’t get your hopes up too much. It’s really one of the most sober and subdued pieces of futurism I’ve read from the last 100 years, but it gives us a fascinating look at the thinking of the time:

But don’t expect too much. And don’t expect it all at once. For many reasons, we aren’t going to turn things upside down as soon as the last shot is fired in this conflict. The people who risk their money to provide the things you buy are going to hold back to find out if you’ll take it before they plunge too deep. And all their research may be overruled on appeal.

The article says that frozen food will be the food of the future, with refrigerated trucks making regular deliveries to homes that have large freezers in their basements:

Foods—Quick freezing has pretty much passed its tests. People will buy frozen foods, and they’ll also store their own produce in rented lockers or home freezers. Which way will the cat jump? There are some folks who think the frozen food industry may eventually—get that “eventually”—work around to a system whereby you’ll keep a large frozen food locker in your basement, and make your purchases from a refrigerated delivery truck that comes around every week or so.

The article has a little fun with the idea that huge windows would be in fashion after the war, but may not be terribly practical:

Housing—It isn’t cricket to throw cold water on your ideas about letting the sun heat your home through huge plate glass windows. But please bear in mind that Mama is going to have something to say, too, and if your big windows open up the innards of your house to prying eyes 20 feet across the lot line, you may come in some fine sunny day to find the drapes drawn and the furnace pumping away.

The piece pointed out that advances in medicine would revolutionize our world, though they may not get as much attention as advances in consumer goods.

Medicine—Among all the scientific advances being made during the war, medicine and surgical methods probably will draw the least public attention, but they probably will influence your post-war life more than any other. The mold drugs give one example. Penicillin, the wonder mold derivative, already has been released, in controlled amounts, to the public.

And speaking of consumer goods, the writer acknowledges the sales pitches that were so common from peddlers of the era:

Household appliances—When the post-war planner regales you with stories about automatic washers, ironers, dish washers, garbage disposal machines, tell him to smile when he says it. You had all those things before the war, and you’ll have them again, if you’ve got what it takes—and that’s money and time to wait for more to be made.

In describing the community of tomorrow the writer makes reference to an illustration from 1895 that humorously imagined the future. The writer predicts that any changes in the community of the future really can’t be foreseen, but will likely be basic and simple.

Community Planning—A half century ago an artist did the same kind of thinking about his future that many people today are doing about ours. He came up with an idea of what the skyscraper of the future—say about now—would look like. He reserved a large section of the building for a hay and feed store! He reckoned without the automobile, which was to change the whole complexion of things within 10 years and make his drawing appear fantastic. We can still count on a wonderful new world opening up before our eyes, but the man who promises you a preview of it just can’t deliver. The furbelows and fripperies that ease the life of the next generation are going to be governed largely on basic, probably simple, changes in our way of living that perhaps no one today can see.

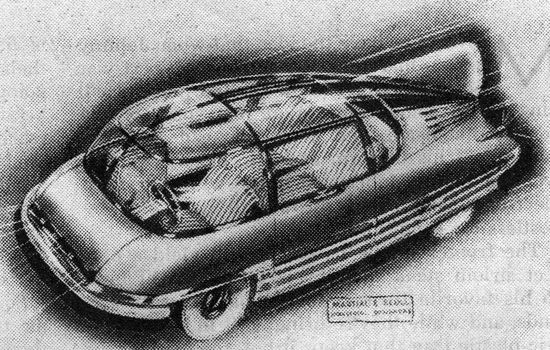

The writer expects that tomorrow’s cars will be leaner and more efficient with engineers figuring out how to produce more with less. Curiously, he also holds out hope for a steam-powered car.

Motoring—On the basis of our wartime scare on the scarcity of petroleum products, it would almost seem safe to predict that the automobile of the future will be lighter and more efficient, getting as much as 50 or 100 miles to a gallon of the best grades of gasoline. The engineers probably will add strength while casting off weight. But who is to say that we won’t be extracting a fuel like gasoline from other products that will permit us to continue running our two-ton heaps because, if for no other reason, we like ‘em? And besides, although steam was tried and discarded once as an automobile power source, such improvements have been made in boilers and heating plants, as well as in the engines themselves, it is entirely possible someone will market, some day, a steam automobile that will go when you press your foot on the accelerator first thing in the morning. There are startling things afoot in both power and fuel developments. But they will be announced slowly and carefully. Watch also transmissions, especially in the hydraulics and electrical fields.

The writer predicts quite accurately that after the war the American public will see FM radio and television.

Radio—What can we look for may be these things:

- At first, a set just like we’ve always had, because the manufacturer will have all he can do at first just to fill the demand.

- Then, likely, FM, because it was about ready for the public when the conflict started, and the transmitters are already reaching a good portion of listeners.

- Television—later. Because of the short carrying qualities of television waves, it will come out first in heavily populated centers where there are transmitters.

The machine tools of war are seen as the most obvious advances that would be quickly converted for peacetime purposes.

Machine Tools—It’s most likely that the greatest advances are being made now, and not waiting until after victory is won. The stress and pressure for speedy production is bringing about advancement in the field of specialized machine tools that make our country the undisputed leader of the world’s industrial production. It may be this will prove our real victory in the war.

Futurists of the 1940s had a particular interest in helicopters, predicting that there would be a flying machine in every garage after the war. But the writer of this article is quick to explain the hurdles to such a helicopter-centric society.

Aircraft—A helicopter in your back yard? The picture is bright. You go out behind the apple tree, give the rotors a whirl, and whizz!—you’re on the office roof. At the end of the day, whizz!—and you’re back in Suburbia, tending your delphiniums. Beautiful picture, isn’t it? But you’ll probably have to keep your machine in perfect condition, to be passed on by some safety agency, and it won’t be the perfunctory windshield wiper and horn test, either. The neighbors may not care if you crack your own skull, but they won’t want you doing it on their sun porches. So for some years after the war is over, the first helicopters, and other airplanes for that matter, will be flown by people who can scrape together enough money to insure: (1) a machine in perfect condition; (2) maintenance that will keep it that way; (3) expert training in the operation of the machine. The designers say helicopters are harder to fly than airplanes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)