Black Lives Certainly Mattered to Abraham Lincoln

A look at the president’s words and actions during his term shows his true sentiments on slavery and racial equality

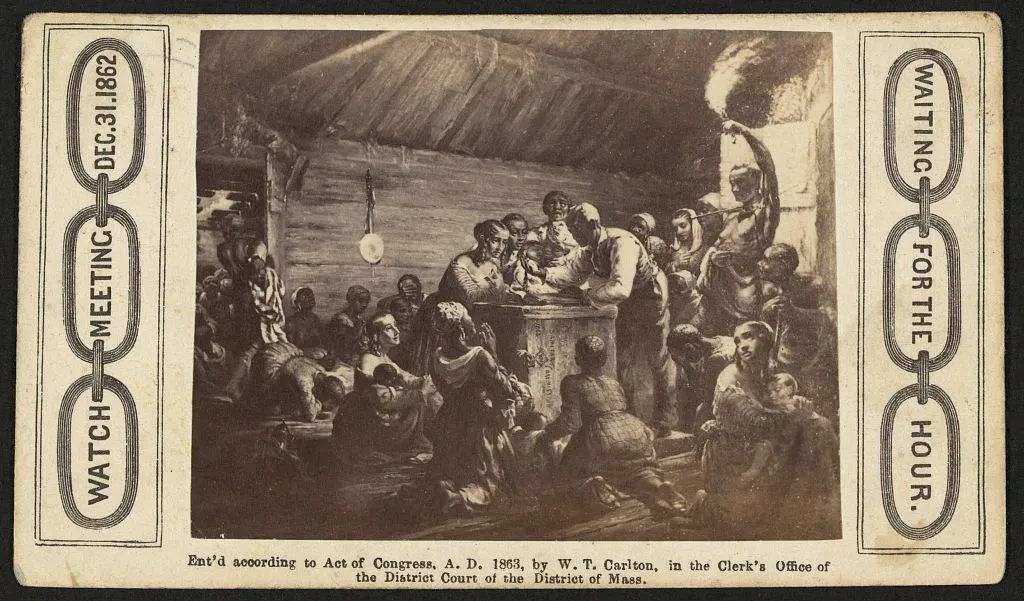

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/2f/d52f07b0-050f-42ba-aa22-a71a3031acac/service-pnp-pga-03800-03898v.jpg)

Last month, the San Francisco Unified School District voted to rename Abraham Lincoln High School because of the former president’s policies toward Native Americans and African Americans.

As Jeremiah Jeffries, chairman of the renaming committee and a first grade teacher, argued, “Lincoln, like the presidents before him and most after, did not show through policy or rhetoric that black lives ever mattered to them outside of human capital and as casualties of wealth building.”

Such a statement would have perplexed most Americans who lived through the Civil War. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared enslaved people in areas under Confederate control to be “forever free.” Two years later he used all of the political capital he could muster to push the 13th Amendment through Congress, permanently abolishing slavery in the United States.

Lincoln’s treatment of Native Americans, meanwhile, is a complex issue. Writing for Washington Monthly in 2013, Sherry Salway Black (Oglala Lakota) suggested that the “majority of his policies proved to be detrimental” to Indigenous Americans, resulting in significant loss of land and life. Critics often cite Lincoln’s approval of the executions of 38 Dakota men accused of participating in a violent uprising; it remains to this day the largest mass execution in United States history. Lincoln’s detractors, however, often fail to mention that the president pardoned or commuted the sentences of 265 others, engaging in “by far the largest act of executive clemency in American history,” per historian James M. McPherson in The New York Times.

The San Francisco committee opted not to consult any historians when considering the renaming, which Jeffries justified by saying, “What would be the point? History is written and documented pretty well across the board. And so, we don’t need to belabor history in that regard.”

But the point should be belabored.

During the Civil War, Lincoln worked assiduously to expand rights for African Americans. In response, most black Americans who lived through the war looked to him with great admiration and respect.

Among the thousands of letters that arrived at the White House during the Civil War, at least 125 came from African Americans. Their missives discussed a wide range of topics, including military service, inequality in society, the need for financial assistance, and the protection of their rights. One black soldier, for example, wrote, “i have ben sick Evy sence i Come her and i think it is hard to make A man go and fite and wont let him vote . . . rite soon if you pleze and let me no how you feel.” Other constituents sent gifts and poems to the president. To be sure, Lincoln saw very few of these letters, as his private secretaries typically routed them to other federal departments. But when presented with a case in which he could intervene, Lincoln often did so.

Some of the most touching letters showed the personal connection that enslaved men and women felt with the president. In March 1865, one black refugee from Georgia wrote, “I take this opportunity this holy Sabbath day to try to express my gratitude and love to you. With many tears I send you this note through prayer and I desire to render you a thousand thanks that you have brought us from the yoke of bondage. And I love you freely.”

He then proceeded to describe a dream he’d had many years before, in which “I saw a comet come from the North to the South and I said good Lord what is that?” The man’s enslaver “threatened my life if I should talk about this. But I just put all my trust in the Lord and I believe he has brought me conqueror through.”

The comet in this dream, this correspondent believed, was Lincoln.

The president, in turn, was so touched by the letter that he kept it in his personal collection of papers, which is now housed at the Library of Congress.

Lincoln also met hundreds of African Americans in Washington during the war years. Some came to the White House at his invitation; others walked through the White House gates uninvited and unannounced. Regardless of how they arrived at his doorstep, the president welcomed these visitors with open arms and an outstretched hand. As Frederick Douglass was proud to say after his first White House meeting in August 1863, Lincoln welcomed him “just as you have seen one gentleman receive another.”

Black visitors to the White House often remarked that Lincoln treated them with dignity and respect. Many were touched by how he shook their hands and made no acknowledgement of their race or skin color. Lincoln’s hospitality toward African Americans came to be well known at the time: As white Union nurse Mary Livermore observed, “To the lowly, to the humble, the timid colored man or woman, he bent in special kindliness.” Writing in 1866, a Washington journalist similarly noted that the “good and just heart of Abraham Lincoln prompted him to receive representatives of every class then fighting for the Union, nor was he above shaking black hands, for hands of that color then carried the stars and stripes, or used musket or sabre in its defense.”

Lincoln appears to have always shaken hands with his black guests. And, in almost every instance, he seems to have initiated the physical contact, despite the fact that shaking hands, for Lincoln, could be an understandably tiresome chore. “[H]e does it with a hearty will, in which his entire body joins,” wrote one observer, so that “he is more weary after receiving a hundred people than some public men we could all name after being shaken by a thousand.” Yet the president warmly, kindly, eagerly and repeatedly grasped the hands of his black guests.

This seemingly small gesture should not be discounted, for it carried not only great personal meaning for the visitors, but also important symbolic meaning for all Americans who witnessed the encounters or read about them in the newspapers. Most white politicians would not have been so genuinely welcoming to African Americans. As historian James O. Horton and sociologist Lois E. Horton wrote in 1998, black Americans “often worked with white reformers … who displayed racially prejudiced views and treated [them] with paternalistic disrespect,” including refusals to shake their hands. Reformers continued to offer snubs like this in the postwar period. During his run for the presidency in 1872, for example, newspaper publisher Horace Greeley ostentatiously showed disdain for a black delegation from Pennsylvania that sought to shake his hand.

Not so with Lincoln.

On April 29, 1864, a delegation of six black men from North Carolina—some born free, others enslaved—came to the White House to petition Lincoln for the right to vote. As the men approached the Executive Mansion, they were directed to enter through the front door—an unexpected experience for black men from the South, who would never have been welcomed this way in their home state. One of the visitors, Rev. Isaac K. Felton, later remarked that it would have been considered an “insult” for a person of color to seek to enter the front door “of the lowest magistrate of Craven County, and ask for the smallest right.” Should such a thing occur, Felton said, the black “offender” would have been told to go “around to the back door, that was the place for niggers.”

In words that alluded to the Sermon on the Mount, Felton likened Lincoln to Christ:

“We knock! and the door is opened unto to us. We seek, the President! and find him to the joy and comfort of our hearts. We ask, and receive his sympathies and promises to do for us all he could. He didn’t tell us to go round to the back door, but, like a true gentleman and noble-hearted chief, with as much courtesy and respect as though we had been the Japanese Embassy he invited us into the White House.”

Lincoln spoke with the North Carolinians for some time. He shook their hands when they entered his office and again when the meeting ended. Upon returning home, the delegation reported back to their neighbors about how “[t]he president received us cordially and spoke with us freely and kindly.”

Outside of the White House, Lincoln also showed kindness toward the black Americans he encountered. In May 1862, he visited an army hospital at Columbian College (now George Washington University) where a white nurse introduced him to three black cooks who were preparing food for sick and wounded soldiers. At least one of the cooks had been previously enslaved. Lincoln greeted them in “a kindly tone,” recalled the nurse. “How do you do, Lucy?” he said to the first. The nurse then remarked that he stuck out his “long hand in recognition of the woman’s services.” Next Lincoln gave the two black men a “hearty grip” and asked them, “How do you do?”

When the president left the room, the three black cooks stood there with “shining faces” that testified to their “amazement and joy for all time.” But soon, sadly, the nurse realized what the convalescing Union officers thought of this scene. They expressed a “feeling of intense disapprobation and disgust” and claimed that it was a “mean, contemptible trick” for her to introduce them to the president.

Lincoln has received a good deal criticism in the modern era for his views on race. For much of his adult life—including during part of his presidency—he pushed for African Americans to voluntarily leave the United States through a process known as colonization. In August 1862, he condescendingly lectured a delegation of black Washingtonians about why they should endorse this policy. As unfortunate as this meeting appears in retrospect (and it did to many at the time as well), he invited these men to his office in order to accomplish a larger political purpose. Soon afterward Lincoln publicized his words in the newspapers, hoping that they would help prepare the northern electorate for executive action regarding slavery. In essence, he hoped to persuade white voters not to worry about emancipation because he would promote policies that were in their best interest. Meanwhile, Lincoln was planning to do something momentous and unprecedented—issue his Emancipation Proclamation.

Many today also criticize Lincoln for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation as a “military necessity”—a policy to help win the war—rather than as a clarion call for justice. Such views have gained currency in the broader popular culture. In 1991, for example, Tupac Shakur rapped, “Honor a man that refused to respect us / Emancipation Proclamation? Please! / Lincoln just said that to save the nation.” But the truth is, Lincoln needed to justify his controversial action constitutionally—as a war measure—so that it could hold up in court if it were challenged. Taking this approach does not diminish Lincoln’s deeply held moral beliefs about the immorality of slavery. As he said upon signing the proclamation, “my whole soul is in it.” Indeed, Lincoln issued the proclamation out of moral duty as well as military necessity, as evidenced by a meeting he had with Frederick Douglass toward the end of the war.

By August 1864, Lincoln had become convinced that he would lose reelection, allowing an incoming Democratic administration to undo all he had done to bring freedom to the enslaved. The president invited Douglass to the White House, where the two men devised a plan to encourage people still held in bondage to flee to Union lines before Lincoln would be out of office, should he lose. Lincoln said, “Douglass, I hate slavery as much as you do, and I want to see it abolished altogether.”

Lincoln’s plan had nothing to do with helping him win the war (“military necessity”) or the election; it had everything to do with Lincoln’s deep-seated moral disdain for slavery. For his part, Douglass left the meeting with a new understanding of the president’s intense commitment to emancipation. “What he said on this day showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had ever seen before in anything spoken or written by him,” Douglass later wrote.

Fortunately, nothing ever had to come of this desperate plan. The war took a turn for the better, and Lincoln easily won reelection in November 1864.

In the end, Lincoln’s welcoming of African Americans to the White House was an act of political courage and great political risk. Indeed, Douglass, probably more than any other person, understood the significance of Lincoln’s open-door policy. “He knew that he could do nothing which would call down upon him more fiercely the ribaldry of the vulgar than by showing any respect to a colored man,” said Douglass shortly after Lincoln’s death. And yet that is precisely what Lincoln did.

Douglass concluded:

“Some men there are who can face death and dangers, but have not the moral courage to contradict a prejudice or face ridicule. In daring to admit, nay in daring to invite a Negro to an audience at the White house, Mr. Lincoln did that which he knew would be offensive to the crowd and excite their ribaldry. It was saying to the country, I am President of the black people as well as the white, and I mean to respect their rights and feelings as men and as citizens.”

For Lincoln, black lives certainly mattered.