The Black Panthers Were Founded 50 Years Ago, and Their Influence Hasn’t Waned

Group founder Bobby Seale reflects on the Panthers’ iconic Ten-Point Program

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/09/2c09688f-e5e4-4290-800f-7358d746aa57/23bobby_seale10081604.jpg)

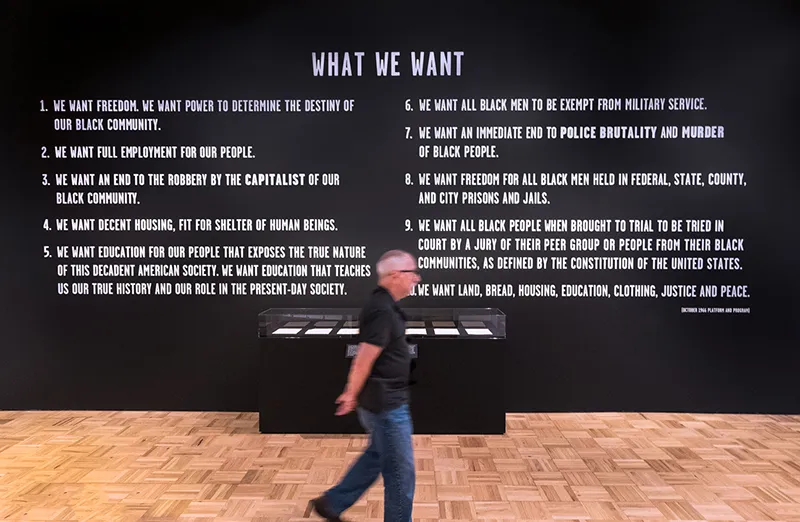

From Black Lives Matter to quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s bended knee, the Black Panthers’ political legacy remains alive in America’s ongoing dialogue about race, justice and privilege. The backbone of their philosophy—a mix of demands and aspirations—is the Party’s Ten-Point Program, written in October 1966 at the North Oakland Neighborhood Service Center.

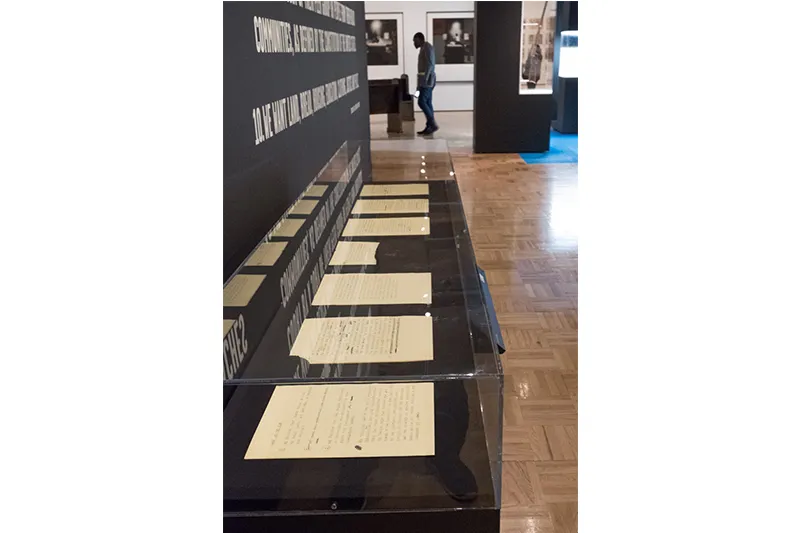

Now on view a few miles from that location, the document is a focal point of a new exhibit at the Oakland Museum of California. The show details the history of the Panthers while honoring the 50th anniversary of the group’s founding.

The Ten-Point Program was the inspiration of two brilliant Oakland college students—Bobby Seale and Huey Newton—whose collaboration gave birth to one of America’s most iconic, and misunderstood, civil rights organizations.

“The Black Panther Party grew out of my heart, mind and soul,” declared Seale at the opening of the exhibit, titled “All Power to the People.” Though he recently turned 80, Seale’s vitality and passion seem undiminished. Looking younger than his years in a blazer and black beret, the eternal Panther radiated charisma. “My concept was this: How do we organize a political electoral unit in our African American communities, extend it across the United States of America, and coalesce with all other peoples who are oppressed? How do we do that?”

Seale’s career began in engineering. In the mid-1960s he was an expert sheet metal mechanic, working at Kaiser Aerospace and Electronics. His passion for social change had taken root in 1962, when he heard Martin Luther King electrify a crowd of 7,000 people at the Oakland Auditorium. “A year later, I quit my job—and went to work in the grassroots communities.”

In 1966, drawing inspiration from King and the Declaration of Independence, Seale and Newton drew up the “Ten-Point Program.” It articulated the demands of an angry, abused community. Some points—“We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people”—were (and remain) incontestable. Others, like the call for all Black prisoners to be freed and all Black men be exempt from military service, provoked an uproar.

But the Panthers didn’t limit themselves to talk. Created to serve and protect the African-American community of the San Francisco Bay Area, they took advantage of California’s “open carry” laws. After a series of killings of unarmed African-Americans, they began patrolling the police in Oakland and nearby Richmond, wearing berets and brandishing rifles. They were quickly demonized by the FBI, caused anxiety among the upper class, and inspired the NRA to support gun control legislation.

Still, the Panthers thrived. Within five years, there were branches in 68 U.S. cities. Of the BPP’s more than 5,000 members, two-thirds were women. And the Panthers did far more than seek justice for victims of police violence. They provided breakfasts for children, ambulance services, escorts for seniors, health clinics, sickle cell screening and food distribution. Their effort became international, beginning in Oakland but eventually embracing the world. By 1970 the BPP was active in nine countries—including Germany, India, Israel and New Zealand.

To much of the American public, the Panthers were seen as dangerous and disruptive. Huey Newton was accused of manslaughter in 1967; he remained in prison until the case was dismissed in 1970. Some Panther groups used extortion and strong-arm tactics to get contributions from local merchants. There were reports of drug dealing, and fierce confrontations with the police. Bobby Seale himself was bound and gagged in court during the famous Chicago Eight trail of 1969—an illegal and much-criticized action that nonetheless portrayed the Panthers as wild and uncontrollable.

A half century after the group’s founding, Seale offered his reflections next to the glass case displaying his original seven-page, handwritten draft of the Ten-Point Program. He can still recite the entire manifesto, word for word, from memory. “It’s in my head,” he nods. “The 10-Point Program is a part of me.” But despite the document’s call for housing, education and justice, the Party’s real mission was political transformation on the highest level.

“Our programs were all connected to voter registration drives,” says Seale. In the mid-1960s, he recalls, there were only 50 black politicians elected in the U.S. “Listen to me,” he said emphatically. “There are 500,000 political seats that one can be elected to in the United States of America.” The Panthers’ efforts bore fruit, eventually bringing more African-Americans into office. One of those was Lionel Wilson, the first Black mayor of Oakland, in 1977. (In 1973, Seale himself had come close to being elected Oakland’s mayor.)

Part of the reason the Panthers dissolved, in 1982, was because of power struggles and ideological differences within the group. Some male Panthers were resistant to the rise of female members as leaders. And the two original founders sparred—violently, by some reports—over the destiny of the Party. “Huey [Newton] tried to make it appear as if he started everything,” Seale says, still bridled by the subject. “He did not. I created, I started it, I was the organizer, I was the person that had the resources.”

Even if the Panthers were Seale’s brainchild, the Ten-Point Program was a joint effort.

“They were my ideas and Huey’s ideas,” says Seale. “The first points were mine, mostly. Right on up to number seven: an immediate end to police brutality and the murder of Black people. That was largely Huey’s. The ninth point—that all Black men and women who were tried in a courtroom by all-white people have another trial—was also Huey’s. Remember, Huey was in law school. Me, I worked for the city.”

But the most poignant and significant element Seale contributed to the Program is its conclusion.

“I chose to put the first two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence at the tail end,” nods Seale. “Huey said, ‘Why are you putting that here?’ I say, ‘Look what it says: ‘…when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.’”

Again, Seale’s ultimate vision was a unified community that would vote in new politicians—Black politicians—across the country. “We’re going to change the racist laws,” Seale told Newton. “We’re going to provide new guidelines to offer security and happiness.”

“If you could add an 11th point to the Program,” I asked Seale, “What would it be?”

“I would add something about ecology,” he replied. “When I tried to introduce ecology to party members in [our] heyday, I couldn’t get my community focused in on what I was talking about— because people were being brutalized, killed and sent to jail.”

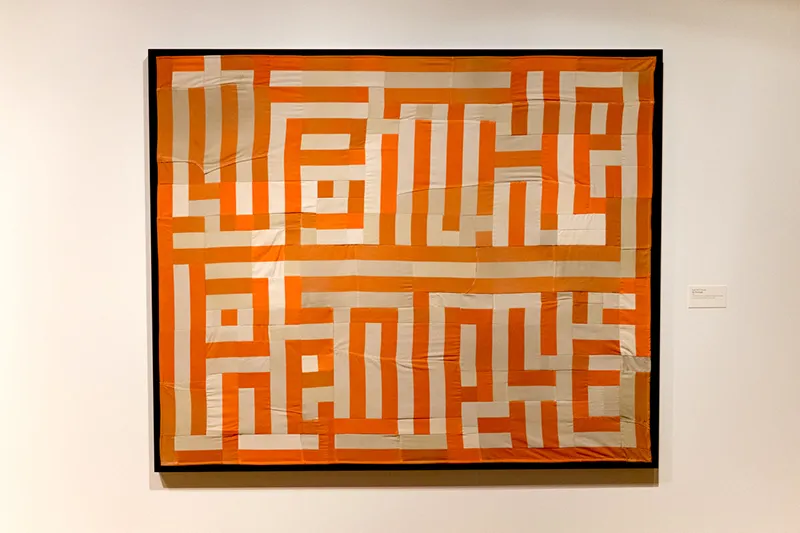

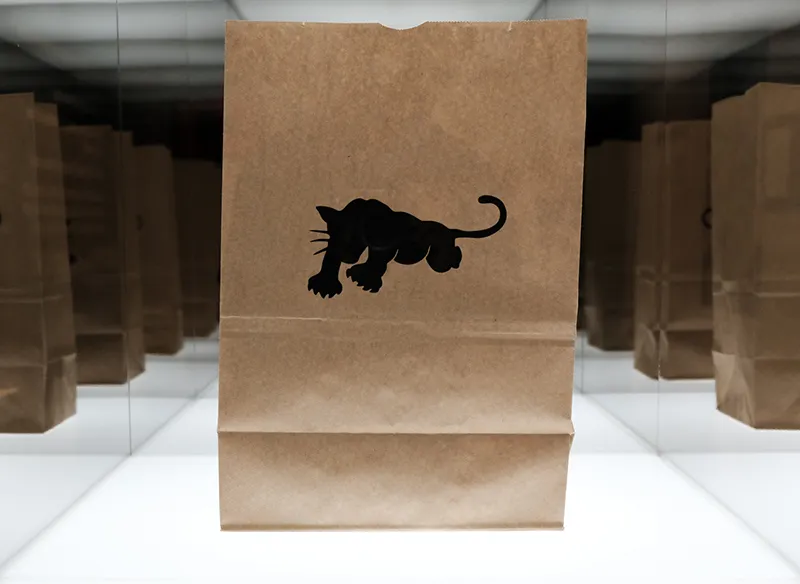

Along with the Ten-Point Program, “All Power to the People” features many rarely seen images and icons. A photograph of the group’s Boston headquarters, freshly ransacked by the FBI, was captured by Stephen Shames; one wall displays Hank Willis Thomas’ “WE THE PEOPLE,” a quilt made entirely out of decommissioned prison uniforms. Other objects include historical artifacts: from a food distribution bag emblazoned with the Panthers’ prowling logo to a personalized, painted rifle.

The exhibit also discusses the FBI’s COINTELPRO (counter intelligence program). Created in 1956 to frame Communists, COINTELPRO’s next big target was the Civil Right Movement. The program’s mandate, provided by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, was to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, neutralize or otherwise eliminate" black activists, from King to rank-and-file Panthers. COINTELPRO spread disinformation within the Panthers, sending forged letters between chapters and pitting leaders against one another. Offices were raided. Spies and informants were planted within Panther cells, and news outlets were fed false stories about their actions and motives.

Of all the things that still rankle Bobby Seale about his Panther days—and there are many—chief among them is being tarred as a “thug.”

“That pissed me off,” bristled Seale. “I ain’t no damned thug! I worked in aerospace electronics for three and a half years. I worked on the Gemini missile program, brother. I was a person with a profession, and I loved my job.

“I’m a human being,” Seale turned to the now substantial crowd surrounding him and the Ten-Point Program. “I’m here fighting for constitutional civil rights for my black folks, and all humanity. Power to the People! That’s where I come from.”

David Huffman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/09/d909801b-905b-417c-bfe3-dd0a388f2787/37bppflaghuey.jpg)

David Huffman’s mother was a graphic artist, and one of the early Black Panthers. Now an artist himself, Huffman recalls his political upbringing with pride.

“I was five years old in 1968. I would have preferred to be sitting at home, watching cartoons—but I was outside of the Alameda County Courthouse, carrying a Free Huey Newton banner," he says. Huffman's mother designed the banner.

“History hasn’t been polite to the Panthers,” Huffman reflects. “I’m hoping this show will dispel the notion of them as a terrorist group, or as troublemakers. As an artist, I’ve been empowered by what I did during that time period.”

M. Gayle "Asali" Dickson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/bd/a6bd1d7a-f84d-423d-8e3d-d9be6c336dd7/18bppgayledickson10061614.jpg)

Dickson was 22 when she joined the Seattle branch in 1970. “We were family” recalls Dickson, who drew the politically charged back page of The Black Panther newspaper. “There was no male/female, no young/old. My sisters and I would walk down the street arm in arm.”

What does Dickson want visitors to get from the show? “Respect. Knowledge. And information,” she says. “Accurate information about who we were—and who we are. Because even though the party ended in 1982, what we were doing—the spirit—is not something you turn on and turn off.”

Sadie Barnette

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c6/9b/c69b5371-86cd-4ed6-923d-c6d59c7bc1bd/14sadiebarnette10061605.jpg)

Rodney Barnette founded the Compton, California chapter of the Black Panther Party. His daughter Sadie, 33, is now an Oakland-based artist. One of 20 contemporary contributions to the show, Barnette’s installation—My Father’s FBI File—displays 198 pages of her dad’s 500-page COINTELPRO file, marked with bright paint and punctuated with family Polaroids that show a different side of a man the FBI viewed as a menace to society.

“He’s referred to as ‘the subject’ in his files,” says Sadie, “but he’s a person. I feel an obligation to tell his story, and learn from my parents’ activism—and how we can apply it today.”

Bryan Shih

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/af/53af488d-a6df-481e-ac7e-6a9b02f4180a/33bppshihphotos.jpg)

Author of The Black Panthers: Portraits of an Unfinished Revolution, New York photographer Bryan Shih’s two paternal great-grandfathers were instrumental in China’s Xinhai Revolution of 1911, which overthrew the country’s last Emperor.

“When I was photographing a different project in San Quentin Prison, I met two gentlemen who had been former Black Panthers. It planted a seed in my mind about what happens to revolutionaries in America.

“I hope people will take away a new view of the humanity of the individuals in the Party—because in many ways the Panthers were demonized, even now, as Black terrorists with guns, trying to kill all white people. And that’s really not what they were about.”