Black Protesters Have Been Rallying Against Confederate Statues for Generations

When Tuskegee student Sammy Younge, Jr., was murdered in 1966, his classmates focused their righteous anger on a local monument

:focal(1642x795:1643x796)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/c0/bcc0678a-e2cf-4880-9911-4d1a5d8395ea/q0000039225.jpg)

Four days after George Floyd was killed by a policeman in Minneapolis, protesters in Richmond, Virginia, responded to his death by targeting the city’s Confederate statues. All along the city’s famed Monument Avenue, the large hulking bronze and stone memorials to Confederate icons Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and the grand statue to Robert E. Lee, were vandalized, and arguably in the case of Lee, transformed into a symbol of resistance.

Protestors spray-painted the statues with their messages of frustration, ripped the Davis statue from its pedestal, and even set the headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy aflame. Many people across the South and the nation were perplexed. Why had the death of a black man in Minnesota led to outrage hundreds of miles away in Virginia? Black southerners saw in Confederate monuments the same issues at the heart of Floyd’s death—systemic racism, white supremacy, and the police brutality that has been generated by those social ills.

It would be a mistake, however, to see the events of last summer as a recent phenomenon, solely a reaction spawned by the nascent Black Lives Matter movement. In truth, these statues have raised the ire of African Americans for more than a century, ever since they were first installed decades after the Civil War. Frederick Douglass called them “monuments of folly,” and when the enormous statue was unveiled to Robert E. Lee in Richmond in 1890, an African American journalist criticized the effort to honor a man who had “bound himself under oath to support and . . . extend the accursed institution of human slavery.”

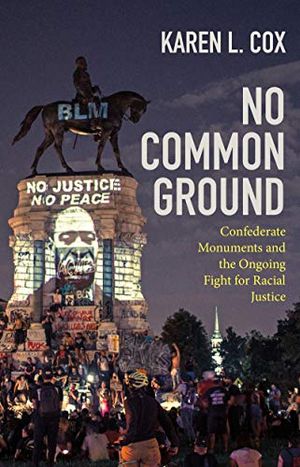

No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice (A Ferris and Ferris Book)

In this eye-opening narrative of the efforts to raise, preserve, protest, and remove Confederate monuments, Karen L. Cox depicts what these statues meant to those who erected them and how a movement arose to force a reckoning.

Today’s Black-led movement to tear down Confederate idolatry also mirrors the case, 55 years ago, when, in 1966, young protestors in Tuskegee, Alabama, exacted their frustrations on the town’s Confederate monument when a white man was acquitted of murdering 21-year-old Sammy Younge, Jr.

Late in the evening of January 3, 1966, Younge stopped to use the bathroom at a local filling station managed by 68-year-old Marvin Segrest. When Segrest pointed him to the “Negro” bathroom, Younge, who was involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Tuskegee Institute (now University), countered by asking him if he’d heard of the Civil Rights Act that made such segregated facilities illegal. An argument ensued between the two men and Segrest pulled a gun and shot Younge in the back of the head, killing him. He admitted as much when arrested.

According to James Forman, who then served as a field director for SNCC in Alabama, “the murder of Sammy Younge marked the end of tactical non-violence.” In the days and months ahead, Tuskegee students and friends of Younge took to the street to express their fury over what had happened to someone so young. Nearly 3,000 people—including students, faculty, staff, and members of the local community—walked into town and called on the mayor to do more than “deplore the incident.”

A Confederate monument of a standalone soldier, dedicated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in 1906, dominated the center of town on land designated “a park for white people.” Officially a memorial to Confederate soldiers from Macon County, it was like many cookie cutter soldier monuments that existed in town squares and on courthouse lawns around the state that made them unwelcoming spaces for Black citizens.

As part of the protest, Tuskegee history professor Frank Toland spoke to students while standing at the base of the monument. Forman called the statue “erected in memory of those who fought hard to preserve slavery.” For a few weeks in January, students protested and vandalized stores in town even as they demonstrated on the land around the Confederate monument. Throughout the year, they also boycotted local businesses.

On December 9, 1966, after a trial lasting just two days, Segrest was acquitted of the murder by an all-white jury in nearby Opelika, Alabama. Even though they had anticipated the outcome, the Tuskegee students were devastated. Student body president Gwen Patton reportedly screamed, “God damn!” after the verdict was read and swiftly returned with her fellow students to Tuskegee to determine their next steps. Near 10:30 p.m. that evening, around 300 students gathered once again in the school’s gymnasium. They were angry and frustrated. “There was this whole fever of blackness,” Patton told Forman, adding, “Negritude was coming across on students.” They decided to march into town, headed to the park where the Confederate monument stood. Feelings about the acquittal were so strong that, by midnight, a group of 2,000 students, faculty and locals had gathered.

What happened next foreshadowed the kinds of protests that have occurred across the South over the last few years. As they gathered around the statue, Tuskegee student Scott Smith saw that people were not of a mind to hold a vigil. They “wanted to do something about the problem . . . so the statue was it.” Smith and classmate Wendy Paris called on someone in the community get them paint, and soon a local man arrived with two cans. They splashed the statue with black paint and smeared a yellow stripe down the back of the soldier atop the pedestal. They also, more pointedly, brushed “Black Power” and “Sam Younge” along the base.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/b3/60b32621-d097-4345-a727-47304d3a578e/q0000054951.jpg)

According to Smith, “When the paint hit, a roar came up from those students. Every time the brush hit, wham, they’d roar again.” The attack on the statue, that symbol of white supremacy in the middle of town, did not end there. They gathered dead leaves and created brush fires around it. One young woman’s pain spilled out and she shouted, “Let’s get all the statues—not just one. Let’s go all over the state and get all the statues.”

The cry to “get all the statues” was a powerful statement and spoke volumes. While it was too dangerous for the students to take out their frustrations on white locals, attacking the monument served as a symbolic attack on racial inequality, as well as on the man who had killed their friend. Her plea revealed her knowledge that nearly every town in Alabama has erected similar statues, constant reminders of racial inequality, which she linked to Younge’s death. It was not something she would have learned in a course in Black history, although Tuskegee would soon add such courses to its curriculum following the protests. It was not something she had necessarily heard from SNCC. Like all Black southerners, her education about the meaning of Confederate monuments came from the lived experience of segregation and racial violence—as attested to by Sammy Younge Jr.’s murder.

The story of what happened in Tuskegee in 1966 serves as a testament to the racial division that Confederate monuments have long symbolized. Frustrations over racial injustice—and daily abuses wrought by individuals dedicated to white supremacy—led then, and leads now, to the vandalism of these statues. Laws that prevent their removal, so-called “heritage protection acts” that currently exist in Alabama and states across the South, undermine racial progress and return attention to established power structures.

Americans cannot look at Confederate monuments as static symbols that do nothing more than reflect some benign heritage. They have contemporary meaning with a racially harmful message. Those who protested Sammy Younge’s murder in 1966 knew that, as did those who protested these same statues in the summer of 2020.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KarenCox.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/KarenCox.jpg)