How Black Women Brought Liberty to Washington in the 1800s

A new book shows us the capital region’s earliest years through the eyes and the experiences of leaders like Harriet Tubman and Elizabeth Keckley

:focal(388x144:389x145)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/92/ba921719-8ef7-4d3c-9865-b63916779432/women_in_dc3.jpg)

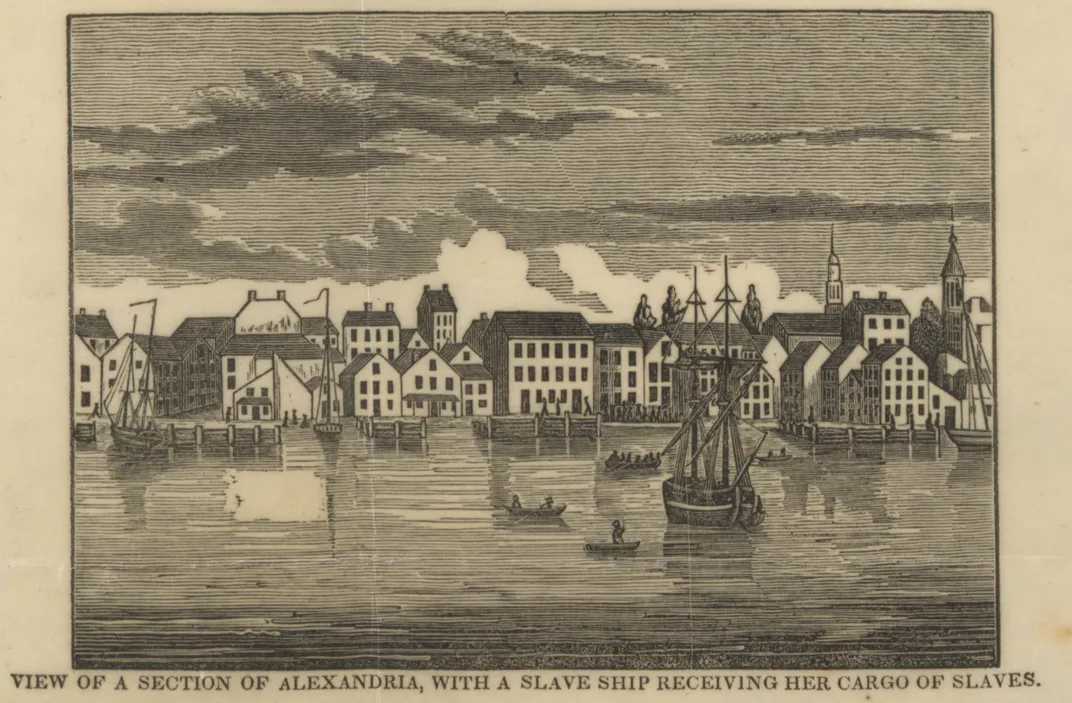

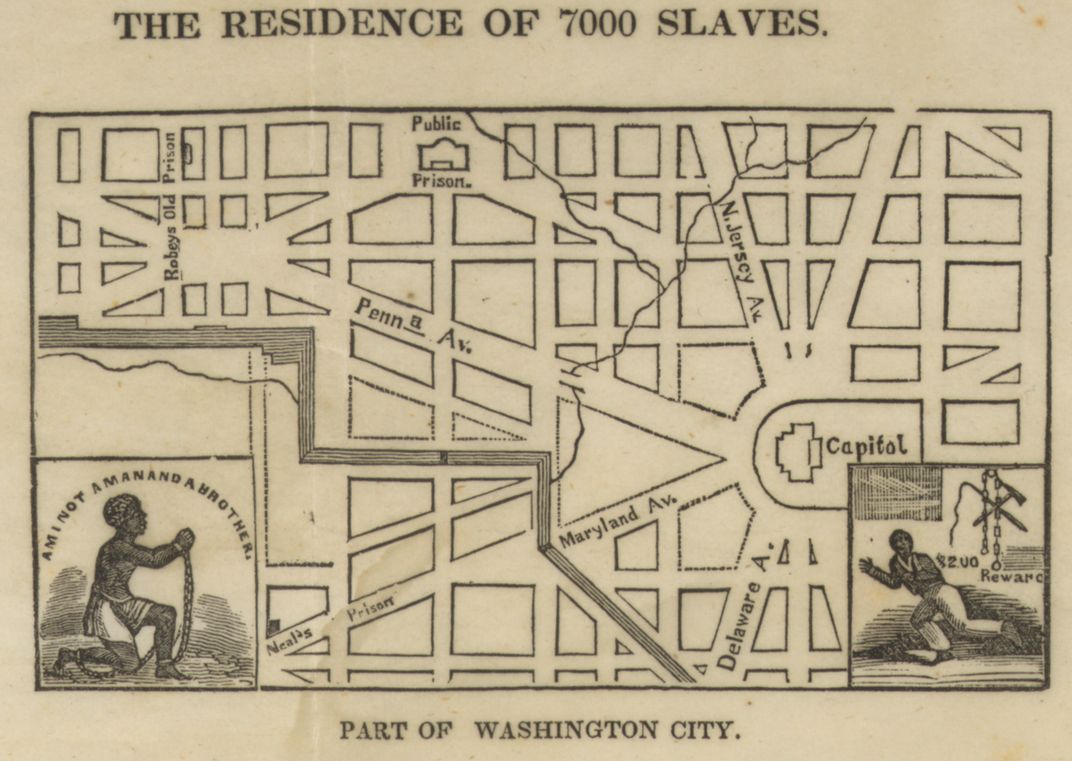

A city of monuments and iconic government buildings and the capital of a global superpower, Washington, D.C. is also a city of people. Originally a 100-square-mile diamond carved out of the southern states of Maryland and Virginia, Washington has been inseparably tied to the African-American experience from its inception, starting with enslavement, in part because of commercial slave-trading in Georgetown and Alexandria. In 1800, the nascent city’s population topped 14,000, including more than 4,000 enslaved and almost 500 free African-Americans.

Before the Civil War, Virginia reclaimed its territory south of the Potomac River, leaving Washington with its current configuation and still a comparatively small city of only about 75,000 residents. After the war the population doubled—and the black population had tripled. By the mid-20th century Washington DC had become the first majority-black city in the United States, called “Chocolate City” for its population but also its vibrant black arts, culture and politics.

In a new book, At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, & Shifting Identities in Washington, DC, historian Tamika Nunley transports readers to 19th-century Washington and uncovers the rich history of black women’s experiences at the time, and how they helped to build some of the institutional legacies for “chocolate city.” From Ann Williams, who leapt out of a second story window on F Street to try and evade a slave trader, to Elizabeth Keckley, the elegant activist, entrepreneur, and seamstress who dressed Mary Todd Lincoln and other elite Washingtonians, Nunley highlights the challenges enslaved and free black women faced, and the opportunities some were able to create. She reveals the actions they women took to advance liberty, and their ideas about what liberty would mean for themselves, their families, and their community.

“I was interested in how black women in particular were really testing the boundaries, the scope of liberty” in the nation’s capital, Nunley says. Putting Washington into the wider context of the mid-Atlantic region, Nunley shows how these women created a range of networks of mutual support that included establishing churches and schools and supporting the Underground Railroad, a system that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. To do that, they navigated incredibly—sometimes impossibly—challenging situations in which as black people and as women they faced doubly harsh discrimination. They also improvised as they encountered these challenges, and imagined new lives for themselves.

Her research took her from the diaries of well-known Washingtonians such as First Lady Dolley Madison to the records of storied black churches to the dockets of criminal arrests and slave bills of sale. Finding black women in historical records is notoriously difficult, but by casting a wide net, Nunley succeeds in portraying individual women and the early Washington, D.C. they helped to build.

At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, and Shifting Identities in Washington, D.C. (The John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture)

Historian Tamika Nunley places black women at the vanguard of the history of Washington, D.C., and the momentous transformations of 19th-century America.

A beautiful photograph of Elizabeth Keckley adorns the cover of your book. She published her memoirs called Behind the Scenes about her life in slavery and then as a famous dressmaker. What does her life tell us about black women in 19th-century D.C.?

Early in the Civil War, as a result of emancipation, many refugees were flocking to the nation's capital and Keckley rose to the occasion, along with other black women, to found the Contraband Relief Society. She's collecting donations, having fundraisers, working her connections with the wives of the political elite, leveraging the Lincoln household, and the Lincoln presidency and her proximity to it in order to raise her profile as an activist in this moment and do this important political work of addressing the needs of refugees. We often assume a monolith of black women. But Keckley was seeing this moment not only as a way to realize her own activism in helping refugees, but she's also realizing her own public persona as someone who is a leader—a leading voice in this particular moment.

Before Keckley and the Lincoln White House, you had Thomas Jefferson, the first President to live his full term in the White House. What role did enslaved women play at the White House where he famously served French food and wine and entertained politicians at a round dinner table?

Even as political leaders were engaged in creating this nation, enslaved laborers were integral. I think about the cook Ursula Granger, who came with him from Monticello at 14 years old, and was pregnant. Despite not knowing a full picture of her story, we know that she was important. The kinds of French cooking she was doing, the kinds of cooking and entertaining that two other women who were there, Edith or Frances, might have been helping with, are some of the same things that we look for today when we are looking at the social world of a particular presidency. There was value that they added to his presidency, the White House, and to life and culture in those spaces.

How did slavery become so important to the early history of Washington, D.C.?

The federal city is carved out of Virginia and Maryland. To cobble together what's going to be the nation's capital, Congress relied on legal precedent from those slaveholding states in order to begin to imagine what this capital is going to be. Politicians who come from the South want to be able to conduct the business of Congress and Senate while also being able to bring their slaves and their entourage and the comforts of home with them. [The creation of Washington] becomes this national symbol of compromise, but also a place of contestation, not only between abolitionists and pro-slavery political thinkers, but also the black inhabitants themselves who were opposed to slavery.

In 1808, the transatlantic importation of African captives was outlawed. At the same time, in Virginia and Maryland there was no longer a huge need for gang labor slavery on large plantations that had been producing tobacco. Instead, deep south states were starting to produce sugar and cotton and many of the "surplus" slaves from the Chesapeake region end up being sold into the deep south. Washington and also Richmond become important hubs for slave traders to organize and take those enslaved people further south.

Another phenomenon is the hiring out system in which people might rent out a slave for a period of time. This became a very prominent practice not only in Washington, but also in rural areas with smaller households. This impacts women in particular ways. Many of these hired out slaves are women who were coming to work for households in the capital. When you look at bill of sale records, you see lots of women and their children being exchanged intra-regionally around the Chesapeake and D.C. in order to meet this demand.

Ann Williams leapt out a window from a tavern right in an act of refusal from being sold into slavery, into the deep South. Resistance was happening even in the city where it seems unlikely because of the degree of surveillance. These acts of desperation are really tough to grapple with. I can never give you an accurate picture of what Ann or others were thinking, but I can tell you what she did, even at the risk of her life. A lot of these stories are unfinished. There are fits and starts throughout the book, some fuller pictures and some where there is no concluding way to think about their experience other than the fact that it’s devastating.

Within this context, Washington’s black community is developing—and black women are very important to that community.

One of my favorite stories is about Alethia Browning Tanner, an enslaved woman who worked her garden plot and goes to the market to sell her goods, and eventually in the early 19th century made enough money that she was able to purchase her freedom and then the freedom of quite a few of her family members. After she became free, she became quite the entrepreneur and also begins to appear in the historical records as having helped founded a school, one of the first schools to admit African-Americans. [She also shows up] in church records as a founding member of a couple of black churches in D.C.

Her story is, to me, more typical of what was happening in D.C. than maybe some of the more prominent women that are associated with D.C. history. Just imagine the logistical feat of going from having been an enslaved woman to having a small garden plot to now being a philanthropist that is one of the major sources of financial support in order to build these autonomous black institutions.

This mutual support and kinship that manifests in these early decades of the 19th century is really how these black institutions are possible. Even if black men and women are free, they're at the bottom of the economic rung. And so for them to be able to even have these institutions is quite exceptional. But what really makes it happen is this mutual support, this sense of kinship, and this willingness to work together and collaboratively to build something autonomous. And that's how these institutions come about.

So, by the time we get to Elizabeth Keckley, creating the Contraband Relief Society at the 15th Street Presbyterian Church, that church was made possible because of Alethia Tanner! I find a lot of inspiration, just even imagining the leap that you have to make to say, not only am I going to earn this enormous amount of money to purchase a whole lot of family members, but now I'm thinking bigger. I'm thinking about institutions and things that can just be for us.

Networks in and around Washington, led in part by women like Harriet Tubman, helped people escape to freedom. What impact did they have on the region?

Tubman was a part of a broader network, and her ability to return back to the same region to keep taking people to freedom had a lot to do with being linked into networks. And in similar ways, we see that happening with other women in this book. Anna Maria Weems, for example, dressed in men's clothing and pretended to be a boy carriage driver in order to become free from an enslaver in Rockville, Maryland, just outside Washington. But that happened with collaboration with other people within the city.

Studying these networks is incredibly challenging because they're intended to be secret! But what we see is that there's a broader cast of characters that are willing to make this trek, just like Harriet did. Anna's mother, Ara, returned back to help bring a baby across state lines. She was channeling that same ethos as Harriet. And in some ways I kept Harriet as this marginal figure [in the book], not because she is marginal, but because I wanted people to be able to see that other women were also acting in parallel ways, in the same time, in the same region as her. And they were part of a broader network that was spiraling out really from Philadelphia, and then spiraling out both south, and then also further north to Canada.

You write about how these networks also came into play when enslaved blacks were suing to gain their freedom. How successful were these lawsuits?

Oftentimes, the freedom suit is triggered by something: the threat of sale; the sight of seeing slave coffles along the National Mall or Pennsylvania Avenue; a death in the family of the slave holder and knowing that you might be up for sale to resolve the estate debts. For other suits, it really was a hunger for just seeing if manumission was even possible.

The networks become really important. They include lawyers who are willing to represent these enslaved women. These are folks who don't necessarily see black women or black people as racial equals, but they do believe that slavery is a problem. I imagine that once Alethia Tanner became free, she starts telling everybody, “This is what you have to do… You need to go to this person. You need to have this amount of money. And you need to be able to do this and say this.”

Black Washingtonians are mobilizing their own desires to become free. And they're trying to figure out ways through this legal bureaucracy and different logistical challenges in order to realize it.

Tell us a little bit about Anne Marie Becraft, one of the first African American nuns, who opened the first school for African-American girls in 1827.

Whereas many of the other black schools are very much in line with a black Protestant tradition, Becraft founded a school in Georgetown upon a Catholic tradition, which also really illuminates for us the theological diversity of black D.C. Becraft is really deploying a strategy of racial uplift, instructing little girls on how to carry themselves, how to march through the streets in line, how to be tidy and neat, and what to learn and what to focus on and on their own spiritual growth. She models it herself and so, when people see her and her pupils passing down the street, it’s a really interesting visual of what's actually happening ideologically for black women who are in education.

They see schools as this engine for creating the kinds of model citizens that will make claims to equality later on in the century. Much of these schools are an example of black aspirations. They're not just training the students to embody moral virtue. They are training them up to be leaders and teachers that will then translate this tradition to future generations.

D.C. could be an incredibly difficult place for women to earn a living. You write about some pretty desperate choices they faced.

The chapter about prostitution and local entrepreneurial economies helped create my title about the “threshold” of liberty. Even when enslaved women become legally free, what does that mean? There are only so many different professions that black women can enter in order to provide for themselves. And often they are still doing the same kinds of work that they were doing in the context of slavery. So, when legal freedom actually is a reality for them, where do they go from there? What are their options? That picture became very desperate in a lot of ways.

This gives us context for the women who are able to become teachers or own their own businesses. But it also gives us context for why women might go into sex work, into prostitution, into leisure economies. These kinds of industries that are not illegal, but they are seen as immoral and seen as degrading. And so if they were a madam, they were able to realize some of their financial aspirations. But if you were barely getting by, making very little money and a prostitute, it can be incredibly devastating. It can be violent. It can still lead to poverty. You're going to be criminalized. You're subject to surveillance. All those very much circumscribe their ability to thrive.

What kind of sources have you used to tell this history?

The sources for the history of African-American women are not abundant. But there was an opportunity to dig into the worlds of more prominent figures, like first lady Dolley Madison or early Washington social figure Margaret Bayard Smith, and see if I could find some black women in them. I would look in diaries or letters that have been read by scholars in a different context. And lo and behold, I found them. I also looked at as many newspapers as I could, church records, slave bill of sale records, court arrests, arrests and workhouse sentences. I also used the court cases analyzed and transcribed in the O Say Can You See: Early Washington DC, Law & Family website.

I may not have a fuller picture of these women’s lives but I chose to name them anyway, to begin to get the conversation started so that anybody else writing about D.C. can now take that and dive deeper. Part of the process of working with all of these different kinds of sources that are imperfect in their own way, is also in a spirit of transparency to be able to say, this is what I know, this is where the record stops.

You’re very intentional in your use of specific terms to help us understand the history of these women, and Washington, D.C. Could you tell us why liberty, navigation, improvisation and self-making are themes you return to throughout the book?

This book really is about liberty, how Americans have used it in a political national context, but also how people at the time imagined this idea and this concept in their own lives. I was really interested in how black women in particular were really testing the boundaries, the scope of liberty, particularly in the nation's capital.

I also used the terms navigation, improvisation and self-making to make sense of what I was seeing happening in these women’s lives. There are harsh conditions and barriers that are imposed upon these women at and they are learning how to navigate them. Improvisation is how they respond to uncertainty, how they respond to the things that they could not anticipate. And then, self-making, I think, is really important. Because so much of our history around enslaved people and resistance has really emphasized that there are various different ways to resist. Self-making is the imaginative possibilities of these women's worlds. Even where we don't find women in their acts of resistance, these black women, these little girls were imagining their selves, imagining their world, imagining their identities, in ways that we have not even begun to understand.

Editor's note, March 8, 2021: This story has been updated to reflect that Anne Marie Becraft was one of the first African-American nuns in the U.S., not definitively the first.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.