For Generations, Black Women Have Envisioned a Better, Fairer American Politics

A new book details the 200-plus years of trenchant activism, from anti-slavery in the earliest days of the U.S. to 21st-century voting rights

:focal(784x525:785x526)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/66/02668f37-3256-4a9f-898c-515d85adf245/voting_rights2.png)

The traditional narrative of American voting rights and of American women’s history, taught in schools for generations, emphasizes the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 as the pinnacle of achievement for suffragists. A look at the headlines from last month’s centennial commemorations largely confirms women’s suffrage as a critical step in the continuing expansion of rights.

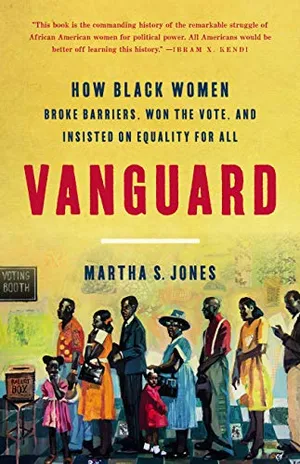

But black women, explains historian Martha S. Jones, have been mostly excluded from both of those arcs. In her new book, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted On Equality For All, Jones reveals more than 200 years of black women’s thinking, organizing, and writing about their vision for an inclusive American politics, including connecting the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 to our contemporary politics and the vice presidential nomination of Senator Kamala Harris, herself African American, in 2020.

Jones writes, too, about the women in her own family across two centuries. She brings these generations of black women out of history’s shadows, from her great-great-great grandmother, Nancy Belle Graves, born enslaved in 1808, to her grandmother, Susie Williams Jones, an activist and educator of the civil rights era. Jones, who teaches at Johns Hopkins University, shows us black women who were active in their churches, in schools and colleges, and in associations, advancing a vision of American politics that would be open to all, regardless of gender or race.

Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All

The epic history of African American women's pursuit of political power—and how it transformed America

What is the Vanguard that you use as the title of the book?

The title came to me very early. The first meaning of vanguard is in the book’s many, many women who were dubbed firsts. Patricia Roberts Harris, the first black woman to be appointed a diplomat during the Johnson administration, explained during her swearing-in ceremony that being first is double-edged. It sounds like a distinction. You broke new ground. But it also means that no black woman came before you. I really took that to heart; it was really a check on the way in which I celebrate the distinction of firsts.

Being in the vanguard also means being out front: leading and showing the way. The women in this book developed a political vision for American politics very early in our history, one that dispensed with racism and sexism. They spent a very long time alone in insisting on that vision. When I explain this about black women’s politics, my students think it's a 21st century idea. But the women I write about were showing that way forward for two centuries. Black women as cutting-edge political leaders is the most important meaning of vanguard.

I wrote a piece recently that called the women of Vanguard “founders,” and maybe I was being a little cheeky. But I do mean that our best ideals today include anti-racism and anti-sexism and it turns out, I think, that they come from black women thinkers early in the 19th century.

How does the story of your own family help us see the connections from the past to today?

The women in my family were a detour in my writing process, but an affirming one. I was in the second draft of the book when it occurred to me that I really didn't know the story of the women in my own family. Then I found my grandmother, Susie Jones, in the 1950s and 1960s in Greensboro, North Carolina, talking about voting rights. If I'd known this story, I would have known why I couldn’t stop the book in 1920, which is what I wanted to do at first. I'm foremost a 19th-century historian and I was aiming for the book to coincide with the 19th Amendment centennial.

When I followed my grandmother’s story, I realized she was telling me I needed three more chapters to take the story all the way to 1965 with the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Readers may know some of the women in the book, like Pauli Murray, the lawyer and civil rights activist who became an Episcopal priest at the end of her life, and others who will be entirely new.

My great aunt Frances Williams will be new to most readers. She came to my mind after a call from historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall when she was finishing her book, and she needed an image of Frances, who appeared in several of her chapters. That was a pleasure; I sit on her living room chairs most days in my own home as I inherited them! So for my book I took a stab at writing about Frances as a voting rights advocate without making any reference to my family. If you're a real detective, you might be able to connect the dots.

Murray is almost irresistible as a subject. She doesn't fit easily into my narrative at first, because as a young woman she’s ambivalent about voting; it’s important to gesture at the ways in which black women were skeptical, critical even of party politics. And while this isn't a book about the black radical women or black women on the left, Murray helps us see that not everyone was in lock-step on the road to a voting rights act or to the polls.

In the end, Murray fit beautifully along the thread of religious activism that runs through the book. Her ordination to the priesthood later in life allowed me to connect the later 20th century with the 19th-century Methodist preacher Jarena Lee who opens the book.

Those institutions, churches, schools and colleges, and associations, are essential for black women’s political work.

Part of the question I'm trying to answer is one about why black women did not flock to women’s conventions. Why aren't they at the 1848 women’s rights meeting at Seneca Falls? The answer is because they were elsewhere, active in black spaces including clubs, anti-slavery societies, civil rights organizations and YWCAs. None of these were labeled suffrage associations, and yet, that's where black women worked out their ideas and did the work of voting rights.

By the time I finished the book, I was convinced that this world was so robust that it really was its own movement, and one that stood apart from the infrastructure of women's political history that we're much more familiar with. Readers will find parts of that familiar narrative in the book, but my goal was to reveal this whole world where black women were at the center, where they were at the helm, where they were setting the agenda.

You write about women in the abolitionist movement, women in the early voting rights movements, in civil rights, and more. Yet these women have been overlooked, even in some of the most iconic moments in American political history, including the famous picture of President Lyndon Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

In addition to Johnson, Martin Luther King, and other men including Ralph Abernathy, this photo features three black women, Patricia Roberts Harris, Vivian Malone and Zephyr Wright. Originally I didn't recognize their faces and didn't know their names. When I found the image in the LBJ Presidential Library, the catalog entry didn't say who they were either. Why didn't we know who those women were? How is it that this photograph, one that is frequently reproduced and held in a presidential library, has been left unexplained?

I actually put out a call on social media and I thought, well, let's see what happens.

It was fascinating because a debate erupted. The identity of Patricia Roberts Harris was clear. Then Vivian Malone has a sister who's still living, and she appeared in my Facebook feed to explain that yes, that was her sister, and that her sister was standing next to Zephyr Wright. Some colleagues suggested other names, and as you know a subject’s identity may not be self-evident with changes in hair styles, clothing and age. But when I heard from Vivian Malone’s sister, I thought, that’s definitive enough for me.

These women turned out to be fascinating because they represent different and somewhat unexpected threads in the complex tapestry of how black women came to politics, and how they came to be involved in voting rights. Harris trained as a lawyer, a very professionalized trajectory, but Wright, who cooked for the Johnson family, is worth understanding also for the role that she played in Johnson's thinking about civil rights. Then Malone, who was the youngest of the three and is sort of fresh from school desegregation and voting rights and the heart of the South, points to another aspect of the story.

Were there other women there? News reports say Rosa Parks was in attendance, but I couldn't confirm that in fact she had been. I raise that to say myths mix with our history and memories when it comes to that moment in the signing of the Voting Rights Act. Perhaps Rosa Parks should have been there, but was she really? It’s not clear.

Can you talk about why it's so important that we understand the 19th Amendment not simply as an achievement of the vote for women?

In 2020, one of our shared questions is, how did we get here? How is it that racism and white supremacy have managed to persist and even permeate politics, law, culture and more, in 2020? It seems important to return to landmark moments and recognize they are pieces of the puzzle. The 19th Amendment is no exception. It was an achievement, but one that colluded with, affirmed and left untroubled anti-black racism and the edifices of white supremacy, particularly when it came to voting rights.

To appreciate how we get here, when we point to, speak of, or decry voter suppression, one root of that scourge lies in the moment of the 19th Amendment. We are the inheritors of a tradition of voter suppression. The years between the Voting Rights Act and the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby v. Holder were exceptional years. More typical in American history is a record of voter suppression, and this helps me to appreciate how intractable and normalized voter suppression is in the 21st century. As a nation we've spent a long time indulging in the self-delusion that voter suppression was something other than just that, even if it has new guises in the 21st century. Teaching that lesson alone, I think, would be enough for me.

It’s a hard lesson to realize that every generation has to do the work of insisting on voting rights, and that the work is arduous, dangerous and more. One of the lessons from black women’s activism in the years after 1920 is that their that voting rights were hard earned. We're not so far from that as we thought we were, I guess.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/db/45dbb935-9891-43b6-bc53-239f381613d8/nine-african-american-women-w-nannie-burroughs.jpg)

The 19th Amendment has played a role in American and women's history, but hasn’t it largely been part of a progressive narrative about the expansion of rights?

We do not do ourselves any favors when we exceptionalize or valorize the road to the 19th Amendment. One of the things I learned in writing Vanguard was about the way in which a narrow focus on the struggle for women's suffrage leaves us ill-equipped for understanding what politics was and is. Yes, the vote is important. But so much more is required and so much more is possible when it comes to political power. Research by legal historian Elizabeth Katz explains that, for example, just because women won the vote, they were not necessarily eligible to hold public office. That remained elusive, even for white women. The history of women’s votes happens in the midst of women’s struggles for many types of political power.

So much of black women’s history is not in traditional archives, but part of what your book shows is how deep and rich the archive of black women’s writing is, the scholarship of black women’s history, and black women’s scholarship.

I need a better metaphor than standing on shoulders of greats. That doesn’t do justice to the debts I owe. When it comes to this book, I don’t think that metaphor does justice to the whole of black women and the scholars who tell their stories upon which Vanguard rests.

Black women have been thinkers and writers, and, even in the early decades of the 19th century, they have left us an archive. My graduate students have really helped me understand the genealogy of black women's history which has its own set of origins in those writings, whether it's Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl published in 1861, or Anna Julia Cooper’s A Voice From the South By a Woman of thee South in 1892, or Hallie Quinn Brown’s Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction in 1926.

As for historians, this book is only possible because generations of black women's historians have done this work. I hope I have done justice to the pioneering research of Rosalyn Terborg-Penn on the history of black women and the vote.

I really wanted a single book that I could put in the hands of non-specialists as an introduction to the complexity of the field. Another historian could take on the same endeavor and produce a very different book. I hope that there is some narrative humility that is somewhere evident in Vanguard; it is neither definitive nor exhaustive.

There are figures in here who need a great deal more study, who need biographies and Mary Church Terrell is getting, finally, a biography from Alison Parker. Keisha Blain is writing a new book about Fannie Lou Hamer. There is so much more to come!

In some ways your book seems very timely, not only because of the centennial of the 19th Amendment, but also because of black women in contemporary politics. At the same time, your work is really timeless.

Isn't that what we'd like all our books to be, both timely and timeless? As a historian, I don't want to write in a way that is so enmeshed in contemporary questions that the book is dated or somehow too much of a moment. Still, so much of what we write today about the African American history past today feels very present, in part because many of our subjects still roil 21st-century politics, culture and law.

African Americanist historians are always writing into the present because the questions that we examined in the past are still questions for today, even if we wish they were not. Still, I know that the archive will surprise me and challenge my expectations. That’s part of what keeps us working and engaged and excited is that treasure hunt. When I began Vanguard, I knew I was writing a book about black women and the vote, but what I would learn and would end up writing, I had to discover in the archives.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.