Blast from the Past

The eruption of Mount Tambora killed thousands, plunged much of the world into a frightful chill and offers lessons for today

The most destructive explosion on earth in the past 10,000 years was the eruption of an obscure volcano in Indonesia called MountTambora. More than 13,000 feet high, Tambora blew up in 1815 and blasted 12 cubic miles of gases, dust and rock into the atmosphere and onto the island of Sumbawa and the surrounding area. Rivers of incandescent ash poured down the mountain’s flanks and burned grasslands and forests. The ground shook, sending tsunamis racing across the JavaSea. An estimated 10,000 of the island’s inhabitants died instantly.

It’s the eruption’s far-flung consequences, however, that have most intrigued scholars and scientists. They have studied how debris from the volcano shrouded and chilled parts of the planet for many months, contributing to crop failure and famine in North America and epidemics in Europe. Climate experts believe that Tambora was partly responsible for the unseasonable chill that afflicted much of the Northern Hemisphere in 1816, known as the “year without a summer.” Tamboran gloom may have even played a part in the creation of one of the 19th century’s most enduring fictional characters, Dr. Frankenstein’s monster.

The eruption of Tambora was ten times more powerful than that of Krakatau, which is 900 miles away. But Krakatau is more widely known, partly because it erupted in 1883, after the invention of the telegraph, which spread the news quickly. Word of Tambora traveled no faster than a sailing ship, limiting its notoriety. In my 40 years of geological work I had never heard of Tambora until a couple of years ago when I started researching a book on enormous natural disasters.

The more I learned about the eruption of Tambora, the more intrigued I became, convinced that few events in history show more dramatically how earth, its atmosphere and its inhabitants are interdependent—an important matter given concerns such as global warming and destruction of the atmosphere’s protective ozone layer. So when the chance arose to visit the volcano while on a trip last fall to Bali and other Spice Islands, I took it.

Indonesia’s Directorate of Volcanology and Geologic Hazard Mitigation said that I should not attempt to climb Tambora—too dangerous. As my guide would later tell me, the name of the mountain means “gone” in a local language, as in people who have vanished on its slopes. But researchers who have studied the volcano encouraged me. “Is it worth it?” I asked Steve Carey, a volcanologist at the University of Rhode Island, who has made the climb. “Oh, my!” he said. That was all I needed to hear.

Through a travel agent in Bima, a city on Sumbawa, a friend and I hired a guide, a translator, a driver, a driver’s mate, a cook and six porters. We filled a van and traveled for hours, weaving among horse-drawn carriages (known locally as Ben-Hurs, after the chariots in the movie) as we headed for Tambora’s southern slope. The parched terrain was like savanna, covered with tall grasses and only a few trees. A few hours west of Bima, the huge bulk of Tambora begins to dominate the horizon. Formerly a cone or double-cone, it’s now shaped like a turtle’s shell: the eruption reduced the mountain’s height by more than 4,000 feet.

We camped a third of the way up the mountain, and set out at dawn for the summit, wending around boulders the size of small cars that were tossed like pebbles from the erupting volcano nearly two centuries ago. Our guide, Rahim, chose a trail that switched back and forth for about four miles. The day was warm and humid, the temperature in the 70s. Grasses in places were charred black, burned by hunters in pursuit of deer.

I was excited to approach the site of one of the most important geological events since human beings first walked the planet. Yet as I looked up at the mountain, I realized I had another purpose in mind. The climb was a chance to reassure myself that after treatment for two kinds of cancer in the past decade, I could still master such a challenge. For me, then, it was a test. For the two porters, striding along in flip-flops, it was a pleasant stroll in the country.

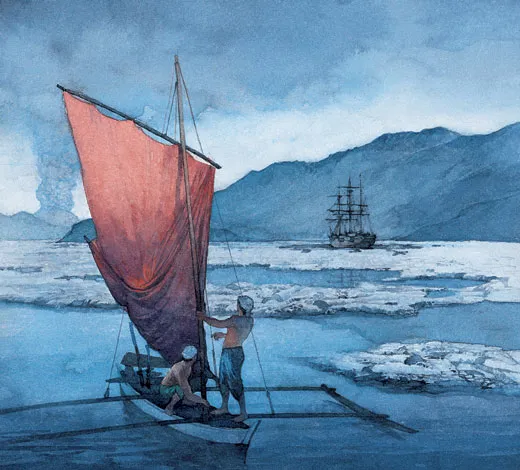

In repose for thousands of years, the volcano began rumbling in early April of 1815. Soldiers hundreds of miles away on Java, thinking they heard cannon fire, went looking for a battle. Then, on April 10, came the volcano’s terrible finale: three columns of fire shot from the mountain, and a plume of smoke and gas reached 25 miles into the atmosphere. Fire-generated winds uprooted trees. Pyroclastic flows, or incandescent ash, poured down the slopes at more than 100 miles an hour, destroying everything in their paths and boiling and hissing into the sea 25 miles away. Huge floating rafts of pumice trapped ships at harbor.

Throughout the region, ash rained down for weeks. Houses hundreds of miles from the mountain collapsed under the debris. Sources of fresh water, always scarce, became contaminated. Crops and forests died. All told, it was the deadliest eruption in history, killing an estimated 90,000 people on Sumbawa and neighboring Lombok, most of them by starvation. The major eruptions ended in mid-July, but Tambora’s ejecta would have profound, enduring effects. Great quantities of sulfurous gas from the volcano mixed with water vapor in the air. Propelled by stratospheric winds, a haze of sulfuric acid aerosol, ash and dust circled the earth and blocked sunlight.

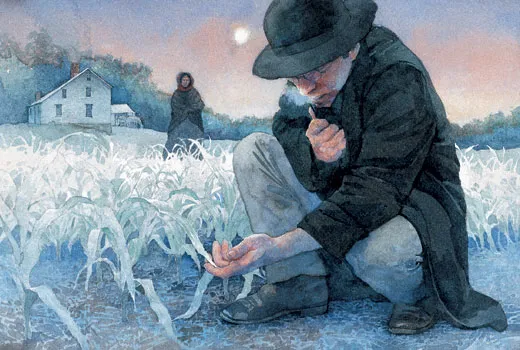

In China and Tibet, unseasonably cold weather killed trees, rice, and even water buffalo. Floods ruined surviving crops. In the northeastern United States, the weather in mid-May of 1816 turned “backward,” as locals put it, with summer frost striking New England and as far south as Virginia. “In June . . . another snowfall came and folk went sleighing,” Pharaoh Chesney, of Virginia, would later recall. “On July 4, water froze in cisterns and snow fell again, with Independence Day celebrants moving inside churches where hearth fires warmed things a mite.” Thomas Jefferson, having retired to Monticello after completing his second term as President, had such a poor corn crop that year that he applied for a $1,000 loan.

Failing crops and rising prices in 1815 and 1816 threatened American farmers. Odd as it may seem, the settling of the American heartland was apparently shaped by the eruption of a volcano 10,000 miles away. Thousands left New England for what they hoped would be a more hospitable climate west of the Ohio River. Partly as a result of such migration, Indiana became a state in 1816 and Illinois in 1818.

Climate experts say that 1816 wasn’t the coldest year on record, but the long cold snap that coincided with the June-to-September growing season was a hardship. “The summer of 1816 marked the point at which many New England farmers who had weighed the advantages of going west made up their minds to do so,” the oceanographer Henry Stommel and his wife, Elizabeth, wrote in their 1983 book about Tambora’s global effects, Volcano Weather. If the ruinous weather wasn’t the only reason for the emigration, they note, it played a major part. They cite historian L. D. Stillwell, who estimated that twice the usual number of people left Vermont in 1816 and 1817—a loss of some 10,000 to 15,000 people, erasing seven years of growth in the Green Mountain State.

In Europe and Great Britain, far more than the usual amount of rain fell in the summer of 1816. It rained nonstop in Ireland for eight weeks. The potato crop failed. Famine ensued. The widespread failure of corn and wheat crops in Europe and Great Britain led to what historian John D. Post has called “the last great subsistence crisis in the western world.” After hunger came disease. Typhus broke out in Ireland late in 1816, killing thousands, and over the next couple of years spread through the British Isles.

Researchers today are careful not to blame every misery of those years on the Tambora eruption, because by 1815 a cooling trend was already under way. Also, there’s little evidence that the eruption affected climate in the Southern Hemisphere. In much of the Northern Hemisphere, though, there prevailed “rather sudden and often extreme changes in surface weather after the eruption of Tambora, lasting from one to three years,” according to a 1992 collection of scientific studies titled The Year Without a Summer?: World Climate in 1816.

In Switzerland, the damp and dark year of 1816 stimulated Gothic imaginings that still entertain us. Vacationing near Lake Geneva that summer, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and his soon-to-be wife, Mary Wollstonecraft, and some friends sat out a June storm reading a collection of German ghost stories. The mood was captured in Byron’s “Darkness,” a narrative poem set when the “bright sun was extinguish’d” and “Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day.” He challenged his companions to write their own macabre stories. John Polidori wrote The Vampyre, and the future Mary Shelley, who would later recall that inspirational season as “cold and rainy,” began work on her novel, Frankenstein, about a well-meaning scientist who creates a nameless monster from body parts and brings it to life by a jolt of laboratory-harnessed lightning.

For Mary Shelley, Frankenstein was primarily an entertainment to “quicken the beatings of the heart,” she wrote, but it has also long served as a warning not to overlook the consequences of humanity’s tampering with nature. Fittingly, perhaps, the eruption that probably influenced the invention of that morality tale has, nearly two centuries later, taught me a similar lesson about the dangers of humanity’s fouling our own atmosphere.

After several hours of hard, slow climbing, during which I stopped frequently to drink water and catch my breath, we reached the precipice that is the southern rim of Tambora. I stared in silent awe down the volcano’s throat. Clouds on the far side of the great crater formed and reformed in the light breeze. A solitary raptor sailed the currents and updrafts.

Three thousand feet deep and more than three miles across, the crater was as barren as it was vast, with not a single blade of grass in its bowl. Enormous piles of rubble, or scree, lay at the base of the steep crater walls. The floor was brown, flat and dry, with no trace of the lake that is said to collect there sometimes. Occasional whiffs of sulfurous gases warned us that Tambora is still active.

We lingered at the rim for a couple of hours, talking quietly and shaking our heads at the immensity before us. I tried to conceive of the unimaginable noise and power of the eruption, which volcanologists have classified as “super-colossal.” I would have liked to stay there much longer. When it was time to go, Rahim, knowing that I would probably never return, suggested I say good-bye to Tambora, and I did. He stood at the rim, whispering a prayer to the spirits of the mountain upon whose flanks he has lived most of his life. Then we made our descent.

Looking into that crater, and having familiarized myself with others’ research on the consequences of the eruption, I saw as if for the first time how the planet and its life-forms are linked. The material that it ejected into the atmosphere perturbed climate, destroyed crops, spurred disease, made some people go hungry and others migrate. Tambora also opened my eyes to the idea that what human beings put into the atmosphere may have profound impacts. Interestingly, scientists who study global climate trends use Tambora as a benchmark, identifying the period 1815 to 1816 in ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica by their unusually high sulfur content—signature of a great upheaval long ago and a world away.