Blue versus Green: Rocking the Byzantine Empire

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120302010119ben-hur-games-ottomans-web.jpg)

“Bread and circuses,” the poet Juvenal wrote scathingly. “That’s all the common people want.” Food and entertainment. Or to put it another way, basic sustenance and bloodshed, because the most popular entertainments offered by the circuses of Rome were the gladiators and chariot racing, the latter often as deadly as the former. As many as 12 four-horse teams raced one another seven times around the confines of the greatest arenas—the Circus Maximus in Rome was 2,000 feet long, but its track was not more than 150 feet wide—and rules were few, collisions all but inevitable, and hideous injuries to the charioteers extremely commonplace. Ancient inscriptions frequently record the deaths of famous racers in their early 20s, crushed against the stone spina that ran down the center of the race track or dragged behind their horses after their chariots were smashed.

Charioteers, who generally started out as slaves, took these risks because there were fortunes to be won. Successful racers who survived could grow enormously wealthy—another Roman poet, Martial, grumbled in the first century A.D. that it was possible to make as much as 15 bags of gold for winning a single race. Diocles, the most successful charioteer of them all, earned an estimated 36 million sesterces in the course of his glittering career, a sum sufficient to feed the whole city of Rome for a year. Spectators, too, wagered and won substantial sums, enough for the races to be plagued by all manner of dirty tricks; there is evidence that the fans sometimes hurled nail-studded curse tablets onto the track in an attempt to disable their rivals.

In the days of the Roman republic, the races featured four color-themed teams, the Reds, the Whites, the Greens and the Blues, each of which attracted fanatical support. By the sixth century A.D., after the western half of the empire fell, only two of these survived—the Greens had incorporated the Reds, and the Whites had been absorbed into the Blues. But the two remaining teams were wildly popular in the Eastern, or Byzantine, Empire, which had its capital at Constantinople, and their supporters were as passionate as ever—so much so that they were frequently responsible for bloody riots.

Exactly what the Blues and the Greens stood for remains a matter of dispute among historians. For a long time it was thought that the two groups gradually evolved into what were essentially early political parties, the Blues representing the ruling classes and standing for religious orthodoxy, and the Greens being the party of the people. The Greens were also depicted as proponents of the highly divisive theology of Monophysitism, an influential heresy which held that Christ was not simultaneously divine and human but had only a single nature. (In the fifth and sixth centuries A.D., it threatened to tear the Byzantine Empire apart.) These views were vigorously challenged in the 1970s by Alan Cameron, not least on the grounds that the games were more important than politics in this period, and perfectly capable of arousing violent passions on their own. In 501, for example, the Greens ambushed the Blues in Constantinople’s amphitheater and massacred 3,000 of them. Four years later, in Antioch, there was a riot caused by the triumph of Porphyrius, a Green charioteer who had defected from the Blues.

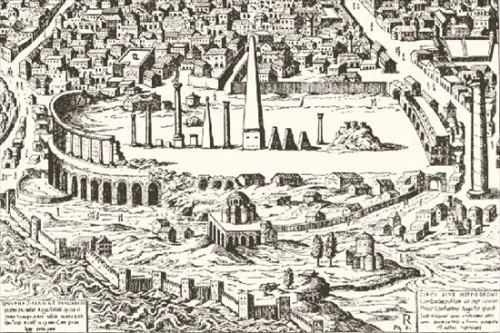

Even Cameron concedes that this suggests that after about 500 the rivalry between the Greens and the Blues escalated and spread well outside Constantinople’s chariot racing track, the Hippodrome–a slightly smaller version of the Circus Maximus whose central importance to the capital is illustrated by its position directly adjacent to the main imperial palace. (Byzantine emperors had their own entrance to the arena, a passageway that led directly from the palace to their private box.) This friction came to a head during the reign of Justinian (c. 482-565), one of Byzantium’s greatest but most controversial emperors.

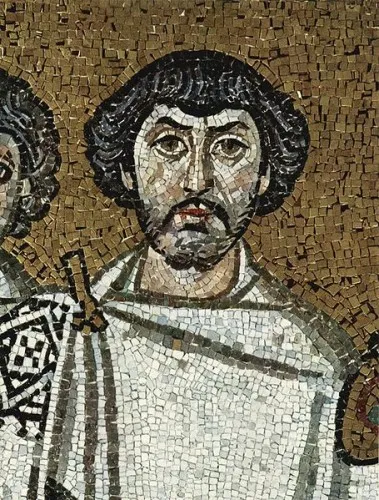

In the course of Justinian’s reign, the empire recovered a great deal of lost territory, including most of the North African littoral and the whole of Italy, but it did so at enormous cost and only because the emperor was served by some of the most able of Byzantine heroes—the great general Belisarius, who has good claim to be ranked alongside Alexander, Napoleon and Lee; an aged but vastly competent eunuch named Narses (who continued to lead armies in the field into his 90s); and, perhaps most important, John of Cappadocia, the greatest tax administrator of his day. John’s chief duty was to raise the money needed to fund Justinian’s wars, and his ability to do so made him easily the most reviled man in the empire, not least among the Blues and Greens.

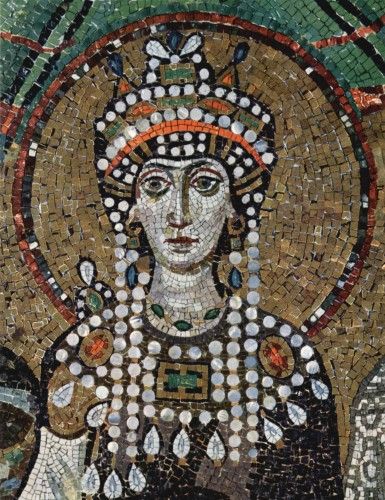

Justinian had a fourth adviser, though, one whose influence over him was even more scandalous than the Cappadocian’s. This was his wife, Theodora, who refused to play the subordinate role normally expected of a Byzantine empress. Theodora, who was exceptionally beautiful and unusually intelligent, took an active role in the management of the empire. This was a controversial enough move in itself, but it was rendered vastly more so by the empress’s lowly origins. Theodora had grown up among the working classes of Byzantium. She was a child of the circus who became Constantinople’s best known actress—which, in those days, was the same thing as saying that she was the Empire’s most infamous courtesan.

Thanks to the Secret History of the contemporary writer Procopius, we have a good idea of how Theodora met Justinian in about 520. Since Procopius utterly loathed her, we also have what is probably the most uncompromisingly direct personal attack mounted on any emperor or empress. Procopius portrayed Theodora as a wanton of the most promiscuous sort, and no reader is likely to forget the picture he painted of a stage act that the future empress was said to have performed involving her naked body, some grain, and a gaggle of trained geese.

From our perspective, Theodora’s morals are of less importance than her affiliations. Her mother was probably an acrobat. She was certainly married to the man who held the position of bear-keeper to the Greens. When he died unexpectedly, leaving her with three young daughters, the mother was left destitute. Desperate, she hastily remarried and went with her infant children to the arena, where she begged the Greens to find a job for her new husband. They pointedly ignored her, but the Blues—sensing the opportunity to paint themselves as more magnanimous—found work for him. Unsurprisingly, Theodora thereafter grew up to be a violent partisan of the Blues, and her unswerving support for the faction became a factor in Byzantine life after 527, when she was crowned as empress—not least because Justinian himself, before he became Emperor, had given 30 years of loud support to the same team.

These two threads—the fast-growing importance of the circus factions and the ever-increasing burden of taxation—combined in 532. By this time, John of Cappadocia had introduced no fewer than 26 new taxes, many of which fell, for the first time, on Byzantium’s wealthiest citizens. Their discontent sent shock waves through the imperial city, which were only magnified when Justinian reacted harshly to an outbreak of fighting between the Greens and the Blues at the races of January 10. Sensing the disorder had the potential to spread, and eschewing his allegiance to the Blues, the emperor sent in his troops. Seven of the ringleaders in the rioting were condemned to death.

The men were taken out of the city a few days later to be hanged at Sycae, on the east side of the Bosphorus, but the executions were botched. Two of the seven survived when the scaffold broke; the mob that had assembled to watch the hangings cut them down and hustled them off to the security of a nearby church. The two men were, as it happened, a Blue and a Green, and thus the two factions found themselves, for once, united in a common cause. The next time the chariots raced in the Hippodrome, Blues and Greens alike called on Justinian to spare the lives of the condemned, who had been so plainly and so miraculously spared by God.

Soon the crowd’s loud chanting took on a hostile edge. The Greens vented their resentment at the imperial couple’s support for their rivals, and the Blues their anger at Justinian’s sudden withdrawal of favor. Together, the two factions shouted the words of encouragement they generally reserved for the charioteers—Nika! Nika! (“Win! Win!”) It became obvious that the victory they anticipated was of the factions over the emperor, and with the races hastily abandoned, the mob poured out into the city and began to burn it down.

For five days the rioting continued. The Nika Riots were the most widespread and serious disturbances ever to occur in Constantinople, a catastrophe exacerbated by the fact that the capital had nothing resembling a police force. The mob called for the dismissal of John of Cappadocia, and the Emperor immediately obliged, but to no effect. Nothing Justinian did could assuage the crowd.

On the fourth day, the Greens and Blues sought out a possible replacement for the emperor. On the fifth, January 19, Hypatius, a nephew of a former ruler, was hustled to the Hippodrome and seated on the imperial throne.

It was at this point that Theodora proved her mettle. Justinian, panicked, was all for fleeing the capital to seek the support of loyal army units. His empress refused to countenance so cowardly an act. “If you, my lord,” she told him,

wish to save your skin, you will have no difficulty in doing so. We are rich, there is the sea, there too are our ships. But consider first whether, when you reach safety, you will regret that you did not choose death in preference. As for me, I stand by the ancient saying: the purple is the noblest winding-sheet.

Shamed, Justinian determined to stay and fight. Both Belisarius and Narses were with him in the palace, and the two generals planned a counterstrike. The Blues and the Greens, still assembled in the Hippodrome, were to be locked into the arena. After that, loyal troops, most of them Thracians and Goths with no allegiance to either of the circus factions, could be sent in to cut them down.

Imagine a force of heavily armed troops advancing on the crowds in the MetLife Stadium or Wembley and you’ll have some idea of how things developed in the Hippodrome, a stadium with a capacity of about 150,000 that held tens of thousands of partisans of the Greens and Blues. While Belisarius’ Goths hacked away with swords and spears, Narses and the men of the Imperial Bodyguard blocked the exits and prevented any of the panicking rioters from escaping. “Within a few minutes,” John Julius Norwich writes in his history of Byzantium, “the angry shouts of the great amphitheater had given place to the cries and groans of wounded and dying men; soon these too grew quiet, until silence spread over the entire arena, its sand now sodden with the blood of the victims.”

Byzantine historians put the death toll in the Hippodrome at about 30,000. That would be as much as 10 percent of the population of the city at the time. They were, Geoffrey Greatrex observes, “Blues as well as Greens, innocent as well as guilty; the Chrionicon Paschale notes the detail that ‘even Antipater, the tax-collector of Antioch Theopolis, was slain.’ ”

With the massacre complete, Justinian and Theodora had little trouble re-establishing control over their smoldering capital. The unfortunate Hypatius was executed; the rebels’ property was confiscated, and John of Cappadocia was swiftly reinstalled to levy yet more burdensome taxes on the depopulated city.

The Nika Riots marked the end of an era in which circus factions held some sway over the greatest empire west of China, and signaled the end of chariot racing as a mass spectator sport within Byzantium. Within a few years the great races and Green-Blue rivalries were memories. They would be replaced, however, with something yet more threatening–for as Norwich observes, within a few years of Justinian’s death theological debate had become what amounted to the empire’s national sport. And with the Orthodox battling the Monophysites, and the iconoclasts waiting in the wings, Byzantium was set on course for rioting and civil war that would put even the massacre in the Hippodrome in sorry context.

Sources

Alan Cameron. Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976; James Allan Evans. The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002; Sotiris Glastic. “The organization of chariot racing in the great hippodrome of Byzantine Constantinople,” in The International Journal of Sports History 17 (2000); Geoffrey Greatrex, “The Nika Revolt: A Reappraisal,” in Journal of Hellenic Studies 117 (1997); Pieter van der Horst. “Jews and Blues in late antiquity,” in idem (ed), Jews and Christians in the Graeco-Roman Context. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006; Donald Kyle, Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007; Michael Maas (ed). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge: CUP, 2005; George Ostrogorsky. History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1980; John Julius Norwich. Byzantium: The Early Centuries. London: Viking, 1988; Procopius. The Secret History. London: Penguin, 1981; Marcus Rautman. Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire. Westport : Greenwood Press, 2006.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)