A Bold New History of the Battle of the Somme

British generals have long been seen as the bunglers of the deadly conflict, but a revisionist look argues that a U.S. general was the real donkey

“On July 1st the weather, after an early mist, was of the kind commonly called heavenly,” the poet and author Siegfried Sassoon recalled of that Saturday morning in northeastern France. This second lieutenant in the Royal Welch Fusiliers and his brother officers breakfasted at 6 a.m., “unwashed and apprehensive,” using an empty ammunition box for a table. At 6:45 the British began their final bombardment. “For more than forty minutes the air vibrated and the earth rocked and shuddered,” he wrote. “Through the sustained uproar the tap and rattle of machine guns could be identified; but except for the whistle of bullets no retaliation came our way until a few 5.9[-inch] shells shook the roof of our dugout.” He sat “deafened and stupefied by the seismic state of affairs,” and when a friend of his tried to light a cigarette, “the match flame staggered crazily.”

And at 7:30, some 120,000 troops of the British Expeditionary Force rose out of their trenches and headed across no man’s land toward the German lines.

That attack 100 years ago was the long-awaited “Big Push”—the beginning of the Somme Offensive and the quest to crack open the Western Front of World War I. The Allied command hoped that a weeklong bombardment had shredded the barbed wire in front of the troops. But it hadn’t. And before sunset 19,240 British men had been killed and 38,231 more wounded or captured, an attrition rate of almost 50 percent. The ground they took was measured in yards rather than miles, and they had to cede much of it back almost immediately in the face of determined German counterattacks. This year’s doleful centennial commemorates by far the worst day in the long history of the British Army.

For many decades, blame for the debacle has been laid at the feet of British high command. In particular, the British overall commander on the Western Front, Gen. Sir Douglas Haig, has been made out as a callous bumbler—“undeniably a butcher, as his severest critics claim, but most of all a pompous fool,” in the judgment of the American author Geoffrey Norman (rendered in an article headlined “The Worst General”). By extension, his fellow generals are supposed, by their dullness and intransigence, to have betrayed the bravery of the soldiers in the trenches—the image of “lions led by donkeys” has been fixed in the British imagination for the last half-century. For most of that time, Haig’s American counterpart, Gen. John J. Pershing, was lionized as a leader whose tenacity and independence built the American Expeditionary Forces into a winning machine.

But that phrase, attributed to the German officer Max Hoffmann, was inserted into his mouth by the British historian Alan Clark, who then appropriated it for the title of his influential 1961 study of World War I, The Donkeys. Clark later told a friend he had “invented” the conversation he was supposedly quoting from. And that blanket judgment is equally bogus. Recent scholarship and battlefield archaeology, previously unpublished documents and survivors’ accounts from both sides support a new view of Haig and his commanders: that they were smarter and more adaptable than other Allied generals, and swiftly applied the harrowing lessons of the Somme, providing an example that Pershing pointedly ignored.

I want to go a step further here and argue that now it is time actually to reverse the two generals’ reputations.

While most Americans may not focus their attention on World War I until the centennial of the U.S. troops’ entry into the fray, in the fall of 2017, the contrast between Haig after the Somme and Pershing after that violent autumn offers a sobering study. Despite the British example, Pershing took an astonishingly long time to adapt to the new realities of the battlefield, at the cost of much unnecessarily spilled American blood. Too many American generals clung to outdated dogma about how to fight the Germans despite plenty of evidence about how it had to be done. A great debate beckons about who was more mulish on the Western Front.

**********

Douglas Haig was the 11th and last child born to a prominent Scotch whiskey distiller and his wife. He was prone to asthma attacks as a child, but his ancestors included several notable warriors, and he came of age when a soldier of the British Empire was the paragon of manliness. He became a soldier.

Dutiful, taciturn and driven, Haig fought in senior roles in two full-scale wars—the Sudan campaign of 1898 and the Boer War of 1899-1902—and then became central to the reform and reorganization of the British Army; his superiors believed he had “a first-class staff officer’s mind.” He spent the decade before the Great War in the War Office, thinking about how Britain might deploy an expeditionary force in France and Belgium if it had to. Still, he was slow to grasp the vicissitudes of mechanized warfare.

Within months after the conflict broke out, in August 1914, the war of maneuver both sides desired was replaced by a system of trenches stretching 400 miles like a gash across northwestern Europe, from the English Channel coast to the Swiss frontier. “War sank into the lowest depths of beastliness and degeneration,” wrote the British Gen. Sir Ian Hamilton. The “glory of war” disappeared as “the armies had to eat, drink, sleep amidst their own putrefactions.”

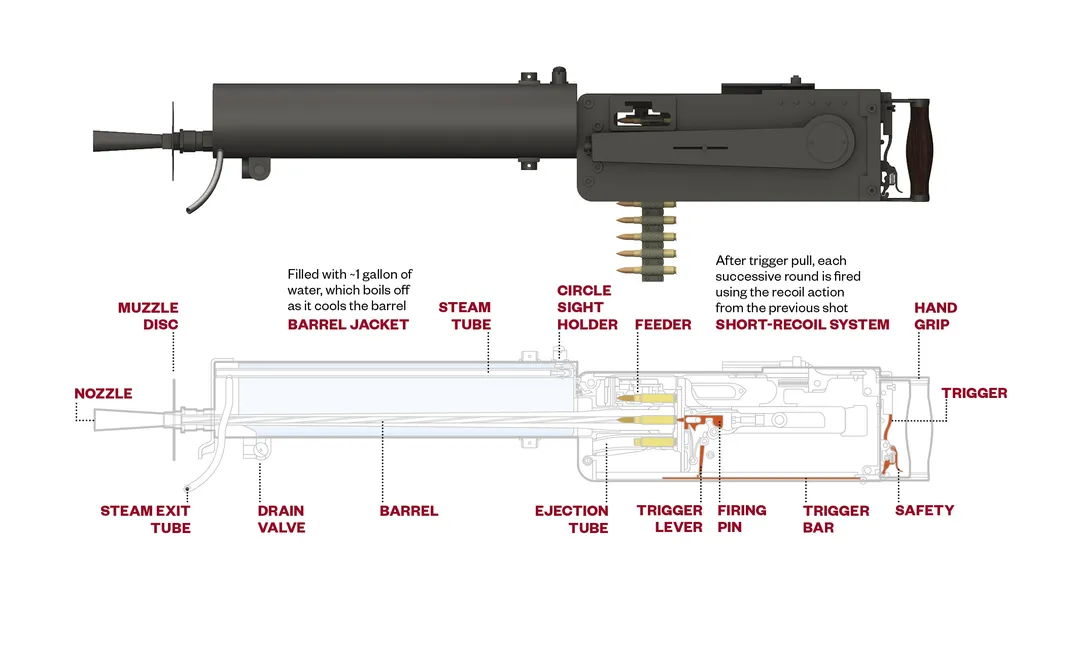

Both sides spent 1915 trying to break through and re-establish the war of maneuver, but the superiority of the machine gun as a defensive weapon defeated this hope time and again. Never in the field of human conflict could so many be mown down so quickly by so few, and the Germans were earlier adopters than the French and British. On the Somme, they deployed a copy of the weapon devised by the American inventor Hiram Maxim—a water-cooled, belt-fed 7.92mm-caliber weapon that weighed less than 60 pounds and could fire 500 rounds per minute. Its optimum range was 2,000 yards, but it was still reasonably accurate at 4,000. The French nicknamed it “the lawnmower” or “coffee-grinder,” the English “the Devil’s paintbrush.”

On February 21, 1916, the German Army took the offensive at Verdun. Within just six weeks, France suffered no fewer than 90,000 casualties—and the assault continued for ten months, during which French casualties totaled 377,000 (162,000 killed) and German 337,000. Over the course of the war, some 1.25 million men were killed and wounded in the Verdun sector. The town itself never fell, but the carnage nearly broke the French will to resist and contributed to widespread mutinies in the army the following year.

It was primarily to relieve the pressure on Verdun that the British and French attacked where and when they did on the River Somme, nearly 200 miles northwest. When the French commander in chief, Gen. Joseph Joffre, visited his counterpart—Haig—in May 1916, French losses at Verdun were expected to total 200,000 by the end of the month. Haig, far from being indifferent to the survival of his men, tried to buy time for his green troops and inexperienced commanders. He promised to launch an attack in the Somme area between July 1 and August 15.

Joffre replied that if the British waited until August 15, “the French army would cease to exist.”

Haig promised Saturday, July 1.

**********

The six weeks between July 1 and August 15 would probably have made little difference to the outcome. Haig was facing the best army in Europe.

Nor could Haig have appealed to the British war minister, Lord Kitchener, to alter the date or place. “I was to keep friendly with the French,” he noted in his diary after meeting with Kitchener in London the previous December. “General Joffre should be looked upon as the [Allied] commander-in-chief. In France we must do all we can to meet his wishes.”

Still, Haig proved to be a good diplomat in a Western coalition that would include the French, Belgian, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, Indian and, later, American armies. Strangely enough, for a stiff-upper-lipped Victorian and devout Christian, Haig as a young officer had been interested in spiritualism, and had consulted a medium who put him in touch with Napoleon. Yet it is hard to detect the hand of either the Almighty or the emperor in the ground that Joffre and Haig chose for the attack of July 1.

The undulating, chalky Picardy farmland and the meandering Somme and Ancre rivers were pitted with easily defended towns and villages whose names meant nothing before 1916 but afterward became synonymous with slaughter. The Germans had been methodically preparing for an attack in the Somme sector; the first two lines of German trenches had been built long before, and the third was under way.

The German staff had constructed deep dugouts, well-protected bunkers, concrete strongpoints and well-hidden forward operation posts, while maximizing their machine guns’ fields of fire. The more advanced dugouts had kitchens and rooms for food, ammunition and the supplies most needed for trench warfare, such as grenades and woolen socks. Some had rails attached to the dugout steps so that machine guns could be pulled up as soon as a bombardment ceased. Recent battlefield archaeology by the historians John Lee and Gary Sheffield, among others, has shown how the Germans in some areas, such as around Thiepval, dug a veritable rabbit warren of rooms and tunnels deep under their lines.

Against these defenses, the British and French high command fired 1.6 million shells over the seven days leading to July 1. The bombardment “was in magnitude and terribleness beyond the previous experience of mankind,” wrote the official historian of the 18th Division, Capt. G.H.F. Nichols.

“We were informed by all officers from the colonel downwards that after our tremendous artillery bombardment there would be very few Germans left to show fight,” recalled Lance Cpl. Sidney Appleyard of Queen Victoria’s Rifles. Some British commanders even thought of deploying horsemen after the infantry punched through. “My strongest recollection: all those grand-looking cavalrymen, ready mounted to follow the breakthrough,” recalled Pvt. E.T. Radband of the 5th West Yorkshire Regiment. “What a hope!”

Yet a large number of British shells—three-quarters of which had been made in America—were duds. According to German observers, around 60 percent of British medium-caliber shells and nearly every shrapnel shell failed to explode. British sources suggest it was closer to 35 percent for each kind. Either way, War Office quality controls had clearly failed.

Historians still debate why. Shortages of labor and machinery, and overworked subcontractors probably explains most of it. Over the next century farmers would plow up so many live, unexploded shells across the battlefield that their gleanings were nicknamed the “iron harvest.” (I saw some freshly discovered ones by the roadside near the village of Serre in 2014.)

Thus when the whistles blew and the men climbed out of their trenches at 7:30 that morning, they had to try to cut their way through the barbed wire. The morning sun gave the machine gunners perfect visibility, and the attackers were so weighed down with equipment—about 66 pounds of it, or half the average infantryman’s body weight—that it was “difficult to get out of a trench...or to rise and lay down quickly,” according to the official British history of the war.

The British 29th Division, for example, mandated that each infantryman “carry rifle and equipment, 170 rounds of small arms ammunition, one iron ration and the rations for the day of the assault, two sandbags in belt, two Mills Bombs [i.e., grenades], steel helmet, smoke [i.e., gas] helmet in satchel, water bottle and haversack on back, also first [aid] field dressing and identity disc.” Also: “Troops of the second and third waves will carry only 120 rounds of ammunition. At least 40 percent of the infantry will carry shovels, and 10 percent will carry picks.”

That was just the soldiers’ personal kit; they also had to carry an enormous quantity of other materiel, such as flares, wooden pickets and sledgehammers. Small wonder the official British history said the men “couldn’t move quicker than a slow walk.”

**********

Most of the day’s deaths occurred in the first 15 minutes of the battle. “It was about this time that my feeling of confidence was replaced by an acceptance of the fact that I had been sent here to die,” Pvt. J. Crossley of the 15th Durham Light Infantry recalled (wrongly in his case, as it turned out).

“A steam-harsh noise filled the air” when the Germans opened up on the 8th Division, recalled Henry Williamson. “[I] knew what that was: machine gun bullets, each faster than sound, with its hiss and its air crack arriving almost simultaneously, many scores of thousands of bullets.” When men were hit, he wrote, “some seem to pause, with bowed heads, and sink carefully to their knees, and roll slowly over, and lie still. Others roll and roll, and scream and grip my legs in utmost fear, and I have to struggle to break away.”

The Germans were incredulous. “The English came walking as though they were going to the theatre or were on a parade ground,” recalled Paul Scheytt of the 109th Reserve Infantry Regiment. Karl Blenk of the 169th Regiment said he changed the barrel of his machine gun five times to prevent overheating, after firing 5,000 rounds each time. “We felt they were mad,” he recalled.

Many British soldiers were killed just as they reached the top of the trench ladders. Of the 801 men of the Newfoundland Regiment of the 88th Brigade who went over the top that day, 266 were killed and 446 wounded, a casualty rate of 89 percent. The Rev. Montague Bere, chaplain to the 43rd Casualty Clearing Station, wrote to his wife on July 4, “Nobody could put on paper the whole truth of what went on here on Saturday and during Saturday night, and no one could read it, if he did, without being sick.”

In Winston Churchill’s judgment, the British men were “martyrs not less than soldiers,” and the “battlefields of the Somme were the graveyards of Kitchener’s Army.”

Siegfried Sassoon’s men were already calling him “Mad Jack” for his reckless acts of bravery: capturing a German trench single-handedly, or bringing in wounded men under fire, a feat for which he would receive the Military Cross on July 27, 1916. He survived the first day of the Somme unscathed, but he would recall that as he and his unit moved out a few days later, they came across a group of about 50 British dead, “their fingers mingled in blood-stained bunches, as though acknowledging the companionship of death.” He lingered on the scene of tossed-aside gear and shredded clothing. “I wanted to be able to say that I had seen ‘the horrors of war,’” he wrote, “and here they were.”

He had lost a younger brother to the war in 1915, and he himself would take a bullet to the shoulder in 1917. But his turn away from the war—which produced some of the most moving antiwar poetry to come out of the Great War—began on the Somme.

**********

As the official British history of the war put it: “There is more to be learnt from ill-success—which is, after all, the true experience—than from victories, which are often attributable less to the excellence of the victor’s plans than to the weakness or mistakes of his opponent.” If there was a consolation for the horrors of July 1, 1916, it is that the British commanders swiftly learned from them. Haig clearly bore responsibility for his men’s ill success; he launched a revolution in tactics at every level and promoted officers who could implement the changes.

By mid-September, the concept of the “creeping barrage” had proved potent: It started halfway across no man’s land to pulverize any Germans who’d crawled out there before dawn, and then advanced in a precisely coordinated fashion, at the rate of 100 yards every four minutes, ahead of the infantry attack. After a system of image analysis for the Royal Flying Corps photographs was developed, the artillery became more accurate. The Ministry of Munitions was revamped, and the ordnance improved.

Above all, infantry tactics changed. Men were ordered not to march line abreast, but to make short rushes under covering fire. On July 1, the infantry attack had been organized mainly around the company, which typically included about 200 men; by November it was the platoon of 30 or 40 men, now transformed into four sections of highly interdependent and effective specialists, with an ideal strength per platoon of one officer and 48 subordinates.

The changes in tactics would have been meaningless without better training, and here the British Expeditionary Force excelled. After July 1, every battalion, division and corps was required to deliver a post-battle report with recommendations, leading to the publication of two new manuals that covered the practicalities of barbed wire, fieldworks, the appreciation of ground and avoiding enemy fields of fire. By 1917, a flood of new pamphlets ensured that every man knew what was expected of him should his officers and NCOs be killed.

A galvanized British Expeditionary Force inflicted a series of punishing defeats on the enemy that year—on April 9 at Arras, on June 7 on the Messines Ridge, and in the September-October phase of Third Ypres, where carefully prepared “bite and hold” operations seized important terrain and then slaughtered the German infantry as they counterattacked to regain it. After absorbing the shock of the German spring offensives in March, April and May 1918, the BEF became a vital part of the drumroll of Allied attacks in which a sophisticated system combining infantry, artillery, tanks, motorized machine guns and aircraft sent the German armies reeling back toward the Rhine.

The effect was so glaring that a captain of the German Guard Reserve Division said, “The Somme was the muddy grave of the German field army.”

**********

The United States had sent observers to both sides starting in 1914, yet the British experience seemed lost on the American high command after the United States declared war in 1917 and its troops began fighting that October. As Churchill wrote of the doughboys: “Half-trained, half-organized, with only their courage, their numbers and their magnificent youth behind their weapons, they were to buy their experience at a bitter price.” The United States lost 115,000 dead and 200,000 wounded in less than six months of combat.

The man who led the American Expeditionary Forces into battle had little experience in large-scale warfare—and neither did anyone else in the U.S. Army. After winning the Spanish-American War in 1898, the United States spent 20 years without facing a major enemy.

“Black Jack” was the polite version of John Pershing’s nickname, bestowed by racist West Point classmates after he commanded the Buffalo Soldiers, the segregated African-American 10th U.S. Cavalry, in battle against the Plains Indians. He showed personal bravery fighting the Apaches in the late 1880s, in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, and in the Philippines up to 1903. But by 1917 he had little experience of active command in anything other than small anti-guerrilla campaigns, such as pursuing, but failing to corral, Pancho Villa in Mexico in 1916. Future Gen. Douglas MacArthur recalled that Pershing’s “ramrod bearing, steely gaze and confidence-inspiring jaw created almost a caricature of nature’s soldier.”

The great tragedy of his life had struck in August 1915, when his wife, Helen, and their three daughters, ages 3 to 8, died in a fire that engulfed the Presidio in San Francisco. He had responded by throwing himself into his work, which crucially did not include any rigorous study of the nature of the warfare on the Western Front, in case the United States got involved. This is all the more surprising because he had acted as a military observer in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 and again in the Balkans in 1908.

And yet Pershing arrived in France with a firm idea of how the war should be fought. He staunchly resisted attempts to “amalgate” some of his men into British or French units, and he promoted a specifically American way of “open” warfare. An article in the September 1914 edition of the Infantry Journal distilled U.S. practice—which Pershing believed in passionately—this way: Infantry under fire would “leap up, come together and form a long line which is lit up [with men firing their weapons] from end to end. A last volley from the troops, a last rush pell-mell of the men in a crowd, a rapid making ready of the bayonet for its thrusts, a simultaneous roar from the artillery...a dash of the cavalry from cover emitting the wild yell of victory—and the assault is delivered. The brave men spared by the shot and shell will plant their tattered flag on the ground covered with the corpses of the defeated enemy.”

Anything further removed from the way war was actually being fought at the time is hard to imagine.

“In real war infantry is supreme,” official U.S. military doctrine held at the time. (It would not acknowledge that artillery had a big role to play until 1923.) “It is the infantry which conquers the field, which conducts the battle and in the end decides its destinies.” Yet on the battlefields of Europe modern artillery and the machine gun had changed all that. Such dicta as “Firepower is an aid, but only an aid” had been rendered obsolete—indeed, absurd.

Even into 1918, Pershing insisted, “The rifle and the bayonet remain the supreme weapons of the infantry soldier,” and “the ultimate success of the army depends upon their proper use in open warfare.”

When Pershing arrived with his staff in the summer of 1917, U.S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker also sent over a fact-finding mission that included a gunnery expert, Col. Charles P. Summerall, and a machine-gun expert, Lt. Col. John H. Parker. Summerall soon insisted that the American Expeditionary Forces needed twice as many guns as it had, especially medium-size field guns and howitzers, “without which the experience of the present war shows positively that it is impossible for infantry to advance.” Yet the U.S. high command rejected the idea. When Parker added that he and Summerall “are both convinced...the day of rifleman is done...and the bayonet is fast becoming as obsolete as the crossbow,” it was considered heretical. The head of the AEF’s training section scrawled on the report: “Speak for yourself, John.” Pershing refused to modify AEF doctrine. As historian Mark Grotelueschen has pointed out, “Only struggles on the battlefield would do that.”

These struggles started at 3:45 a.m. on June 6, 1918, when the U.S. 2nd Division attacked in linear waves at the battle of Belleau Wood and lost hundreds of killed and wounded in a matter of minutes, and more than 9,000 before taking the wood five days later. The division commander, Gen. James Harbord, was a Pershing man: “When even one soldier climbed out and moved to the front, the adventure for him became open warfare,” he said, though there had been no “open” warfare on the Western Front for nearly four years.

Harbord learned enough from the losses at Belleau Wood that he came to agree with the Marine Corps brigade commander there, John A. Lejeune, who declared, “The reckless courage of the foot soldier with his rifle and bayonet could not overcome machine-guns, well protected in rocky nests.” Yet Pershing and most of the rest of the high command held to open-warfare attack techniques in the subsequent battles of Soissons (where they lost 7,000 men, including 75 percent of all field officers). A subsequent report noted, “The men were not allowed to advance by rushes and take advantage of the shell holes made by our barrage but were required to follow the barrage walking slowly at the rate of one hundred yards in three minutes.” The men tended to bunch up on these “old conventional attack formations...with no apparent attempt to utilize cover.”

Fortunately for the Allied cause, Pershing had subordinate officers who quickly realized that their doctrine had to change. The adaptations, tactical and otherwise, of men like Robert Bullard, John Lejeune, Charles Summerall and that consummate staff officer, George Marshall, enabled the best of the American divisions to contribute so hugely to the Allied victory. It was they who took into account lessons the British and French armies had learned two years earlier in the hecatombs of the first day on the Somme.

After the war, Pershing returned home to a hero’s welcome for keeping his army under American command and for projecting U.S. power overseas. The rank of General of the Armies was created for him. But his way of making war was dangerously out of date.

Related Reads

Elegy: The First Day on the Somme